When you take on the psychotherapy role with a child or young person who is recovering from as tough start to life in out-of-home care, there is a real possibility that you will become the most consistent and enduring adult in their life, and of the therapeutic relationship being the most reparative one.

In such circumstances, it is difficult to bring therapy to a therapeutic close, and the child or young person will actively resist and protest this. Some service providers will not even start therapy in circumstances where this might occur, such as among children and young people in residential care, or those with a history of placement changes and breakdowns.

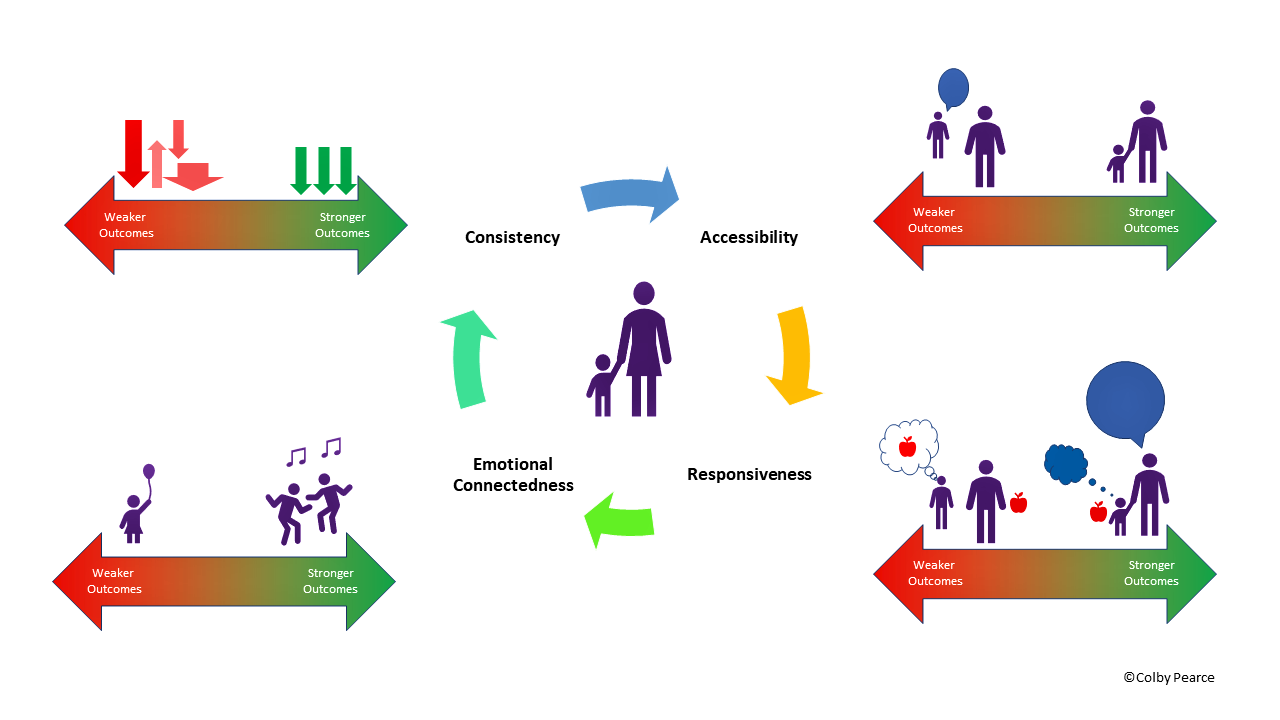

I draw reassurance from the “one good adult” literature and evidence base. Better that the child or young person has/had at-least one good adult in their life. Better again if they also have reparative contact with birth parents/family, stable therapeutic care, stable trauma-informed education placement, and opportunities to form reparative relationships with adults beyond the home and education settings (eg sporting clubs, scouts, cadets, etc).

When these further opportunities for reparative relationships occur, therapy can be meaningfully and therapeutically (and carefully) brought to a close without triggering renewed feelings of grief and loss for the young person, and associated trauma-based responding.

So, therapy must include and/or support endeavours to provide children and young people with opportunities to develop other enduring, sensitive, and responsive relationships through supported (re)connection with birth family, stable therapeutic care placements, trauma-informed care and management in school, and opportunities to engage successfully in community activities.

Ultimately, we need to make ourselves, as therapists, redundant!