In this audio, drawn from one of my supervision sessions with a local organisation, I lead the group through a reflective process considering the question – why are some children unsettled after birth parent contact? The audio is intended to be of most interest to those who interact with children and young people who are recovering from a tough start to life in professional roles.

Disclaimer: While great care is taken to ensure that the information in this audio/video is applicable to childhood trauma and based on sound psychological science, it may not suit the individual circumstances of all viewers. If you have any concerns about applicability to your circumstances, please consult a qualified professional near to you.

Transcript:

So, just looking at my notes from last time, we had a couple of topics that people wanted to talk about. One of them was managing conversations about taking responsibility without invoking shame. And the other one was about managing unsettled behaviour after birth, parent contact.

I’ve got quite a bit to say about managing unsettled behaviour after contact. But probably before I launch into that, and directly relevant to that, I would want you to think about what is the experience of a child, either of birth parent contact and or after birth parent contact. What’s a child’s experience likely to be? We know that all children pay very, even from early infancy, pay very close attention to the face of adults.

And we also know that their own internal state is the homeostasis that their body works to maintain homeostasis. But it does that in a way that is not relevant to or appropriate to the external conditions in which the body is. Yeah.

So, basically, if the parent is anxious, the child will feel anxious. Yeah. Not necessarily, not just because of attunement or emotional connectedness, but also because if the parent is anxious, the child is interpreting this as there’s a threat somewhere.

Yeah. The child’s nervous system is, and it needs to mobilise its threat managing response, which is fight, flight, freeze. What else do you think is the experience of children of contact and the end of contact? So, the carer’s experience is relevant as well.

You’re saying the child will orient to their carer’s face as well. And then there’ll be a response. The nervous system will respond to how it thinks the carer is presenting, or the experience of the carer.

So, if the carer doesn’t like, the carer is anxious about the children going to contact, then the child comes back to the carer, primed, I guess, not so much primed, but will be triggered by the carer, by the carer’s own anxiety or dislike, worry, the feelings that the carer has. But I think it’s, when thinking about this question about managing the unsettled behaviour that the children often exhibit, or at least they’re reported to exhibit and their out-of-home carers report, I think the first place to start is always with the question, well, what is the experience of the child? What’s going on for them? And there’s probably lots of things, they may actually be triggered by their parents as well. The experiences that the children have had with their birth parents triggers a response in them.

Okay. So, just sticking with that, what do you think then, what would the child’s history with their birth parent trigger for the child? What sort of concerns or emotions would contact with their birth parents evoke that we haven’t already mentioned about grief and loss and sadness, pressure? What might the children be worried about as a result of contact? I think I mentioned this to you guys last time. I’ve been talking to people variously about this.

I’m just going to put this in here because I think it’s an interesting place to put it. I’m connected with a lot of care leavers directly through my work and also online. So, on platforms like LinkedIn, there’s the hashtag CEP, which is care experience person.

And there are certain care leavers that are quite prominent, not only through the platforms that they’re on, but they are quite prominent in their work, in their location. And I find it really interesting that care leavers, I’ve rarely if ever seen care leavers blame their parents for their adverse childhood experiences. They seem to be always targeting or the target of their concern is the system, is the way their life was managed by the system growing up, which implies that notwithstanding what happened in their life, well, I think it doesn’t necessarily imply, but it follows that they love their parents.

They often really, really love their parents, notwithstanding their parents’ faults. They want to be good enough, lovable enough, acceptable enough for their parents to be able to take on their care as well. So, children too much, what they internalize from being away from their parents is that there was something wrong with them, not that there was something wrong with their parents, so to speak.

I really think, as I said, I think with all about the aspects of the management of children out of home care, I think the most important question to lead off with is always what’s the experience of child? What’s going on for the child? In my pie shot, my pie thing is what’s really going on? How do we respond to what’s really going on and how do we know that we’ve made a difference? I think they’re the three key questions. The first two, what’s really going on here? How do we respond therapeutically to what’s really going on here? I think children’s experience of contact is variable, but heightened emotion is likely to be pretty common. Heightened emotion, so a dysregulated adult can’t come with dysregulated child, that’s one of those kind of poster statements that you see in this space, but it’s true.

The child will, if their care, return to their care and the carer is highly anxious about, worried about, upset about, angry about the child having gone to contact and now they’re left with picking up the pieces, which is a common thing that they’ll say. Child will is likely to be only further heightened. I think that one of the things that, correct me if I’m wrong, and I think you guys would do it in those families that you’re involved with.

I really don’t know if foster carers and kinship carers fully have a really good understanding of why family contact occurs, birth parent contact occurs. I don’t know that anyone, I’m more than happy to be told that no, it does happen, but my suspicion is that, based on my own interactions with foster and kinship carers, that no one really sits them down and talks to them about why birth parent contact is really important. I think that also would be what comes through from the department having been in the throes of an adversarial court process, or at the beginning, early on in the piece, an adversarial court process where, of course, you’re making an argument.

The workers are party to making an argument that children are not safe with these people. Then the foster parents or the out-of-home carers are sending the children to have contact with unsafe people. No matter how well it’s supervised, I mean, who’d send their own children to go and spend time with unsafe people? I wouldn’t.

I think there’s a response for foster carers to be concerned about contact. I don’t think that it is a sign of a character problem with foster parents. I think that concern about sending the children back off to have contact with unsafe people, I don’t know anyone who cares about their children to not be concerned about that.

I think the natural response for foster carers is to be really concerned about family contact. We’ve primed them to be worried when the children return. What is the impact of this? What are the pieces I’m going to have to pick up? And as I said, I don’t know if it happens.

My suspicion is it doesn’t, partly because what I just said, that we’ve just gone through a process. There was originally a process that really focused in on the faults of the parents to support an argument that children weren’t safe to live with them. It’s antithetical, in a sense, to then turn one’s mind to the enduring importance of birth parents to children, whether the children are living with them or not.

Again, I don’t know how much staff within the agency really understand the importance of birth parent contact. Again, it’s an agency that focuses on risk and risk mitigation. So contact is antithetical to that.

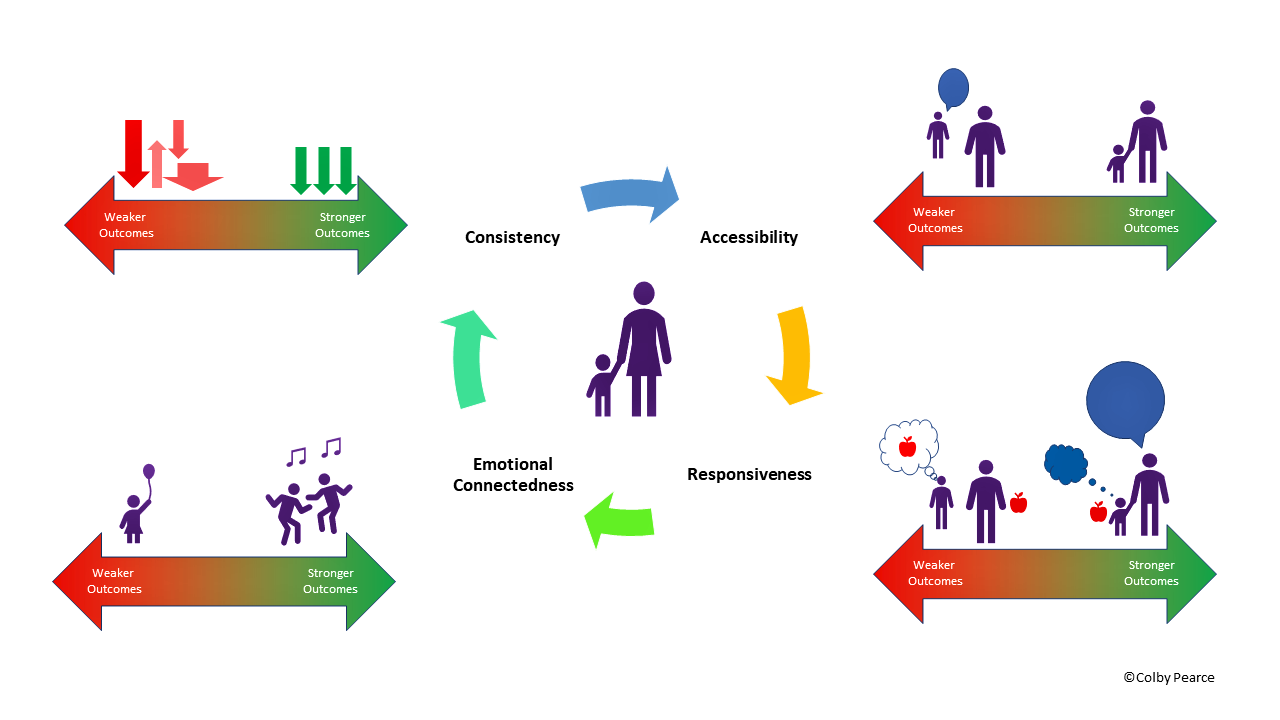

We’ve deviated a little bit, but as you know, I differentiate between attachment relationship and attachment style. Attachment relationship is the dependency relationship that a child forms towards an attachment figure, a significant adult in their life. And that relationship can be secure, or it can be insecure, or it can be disorganized.

And there’s two types of insecure in most classification. That’s an attachment relationship, but it’s not necessarily attachment style. So a child might have a secure attachment to mum, or what looks like a secure attachment to mum.

And remembering that it’s not a yes or no, there are grades of security as such, but it seems like a child has more so a secure attachment to mum and a disorganized attachment to dad. Because dad, and I’m not picking on fellas in this way, but this is more often than not the way it is, because dad not only has been a source of care, but also a source of fear. So in those circumstances, the child exhibits contradictory responses to the adult, okay, and which we call a disorganized attachment.

On the spectrum of attachment, disorganized attachment is at the other end of the spectrum to secure attachment. So what is the child’s attachment style? So the attachment style is their overall insecurity, security, insecurity, or disorganization in the way they approach life and relationships. So we’ve got one secure or semi-secure attachment to mum and a disorganized attachment to dad.

What’s their attachment style likely to be? So you’ve got to think about how is a child likely to approach life and relationships and how are they likely to approach new adults that they interact with, including foster parents or kinship parents, kinship carers. I’m determined to call family carers. I’ve got to get that down pat.

Does anyone think that the child’s overall attachment style would be secure in those circumstances where the two main figures in their life, that the child has a completely different experience of uncertain, unsure, I call them unsure children. Those children often then test new adults, test them and see if they’re going to be more like mum or more like dad. Hands up if you like being tested by children in that way.

Are you going to be mean and nasty or are you going to be kind and caring? Of course, I’m going to be kind and caring. Why would you think I’m not going to be kind and caring? So adults don’t like teachers, out-of-home carers don’t like being tested in this way. So you get this build-up to the child of negative experiences of relatedness to adults.

What’s their attachment style likely to be? I’m not secure. It’s going the other way. It seems to me that there’s a belief that is maintained that as long as we can facilitate the best possible connection with the out-of-home carer, whether that’s kinship or foster or even with key relationships in the residential care placement, that that somehow will neutralise or get rid of the influence of earlier toxic relationships.

The truth is it does a bit and bit by bit. If the children have more and more positive attachment experiences, then it’s going back towards the securing. But as I said, I haven’t heard and I wouldn’t just blame our system here in South Australia.

I think the area of attachment theory around multiple attachment relationships and associated attachment style is not very well looked at. It’s kind of everyone acknowledges that, yeah, yeah, yeah. But at least last time I looked, there’s not a lot of explanation and not a lot of awareness and understanding of the difference between attachment relationship and attachment style.

So there’s not a good understanding of the importance of contact. So people probably only look, as you know and I know, only look at it as a bad thing because the children come back unsettled and the attribution is made that this must be a fear response or an anxiety response or all of these things. Probably not so much grief and loss are imputed or feelings of abandonment.

I try to think about it from my perspective. I haven’t been a child for a long time. I do try to think about what it would be like to be a child who can only visit their parents once a month, knowing that that is their parent, going to school with other children whose parents pick them up at the gate, mum or dad, and drop them off in the morning.

What would it be like for that child? It would be pretty bruising and brutal, I think, in most instances, most instances where it’s deemed safe enough for contact to occur. I think it would be hard on the children. I mean, if the parent is outright terrible and the children have an absolute fear response in relation to the parent, then the contact is unlikely to occur anyway.

So that’s interesting then. So we’ve already, there’s a judgment that has been made that the parents are not that bad. They’re okay enough to have contact with the children.

And I think if they’re okay enough to have contact with the children, then the children are likely to have had a different experience of them prior to removal. Less bad, perhaps. I think at least we should be turning our mind to that.

And sometimes, I was just going to say, my observation would be and understanding would be that sometimes statutory authorities don’t even think about any of these things. They just know that there’s a court order that says that contact has to be arranged every week or every fortnight or every month, and they’re just kind of going through the motions with that. So what’s the experience of the child of having had and having to say goodbye to, having had contact with and say goodbye to their birth parents and go back to their foster placement or their kinship placement or their residential placement? I think that self-doubt is another one.

Am I lovable enough? Does anyone listen to me? Does anyone understand what is my experience of having this contact? Does anyone know what I would like? The children I speak to chronically feel like no one really even considered their point of view. I think to the extent that they’re triggered, there would be children that have some sort of conditioned response. I think the conditioned response is less likely to be fear, but more likely to be, am I loved? Am I lovable enough? Is anyone listening to me? Does anyone care for me? I think that’s more likely to be.

My observation would be that that’s more likely to be the triggered response. It bothers me that children would be turning their minds to what will be the reaction of the adults to what I say. That bothers me a great deal.

How do I manage my relationship with this adult? How do I manage the emotional response, the feelings of this adult? What do I have to say in relation to that? That’s not how the developmental process that ultimately leads to self-regulation and socio-emotional reciprocity works. That developmental process is entirely based around and built upon adults being sensitive and responsive to the experience of children, not the other way around. The child who has contact with parents and is perhaps triggered into thinking, are my views not important enough? Am I not important enough? Am I not lovable enough? They’ll go back to their placement and their carers.

We’re definitely triggered into operating, I think, under this kind of belief system or mindset. I think it’s really important that the experience of the child upon return to their placement makes it really hard for the child to hold on to those ideas about themselves and about arrangements that exist. So the children will act out what they can’t say or won’t say.

And of course, as we all know, if they’re acting out then that contact must be bad and needs to be minimised or eliminated. But what it may be is is that the child will… So for example, a child will just… If they’re coming back anxious and heightened, they’re going to be prone to tensions and meltdowns. Of course they are.

If a child comes back self-doubting, then they’ll act without care for themselves or for their relationships with people around them. Doesn’t matter. Why do you care? That’s what they say.

If I wish I had a dollar. If they come back in grief, contact’s a bad thing because it just makes them feel so uncertain about themselves and so sad. It’s a bit like we don’t look enough at… We don’t look enough at… And we’ve talked about it.

We don’t look enough at the reasons why contact’s important. We just over-focus on all the negatives that come from contact. So yeah, I think, what did I say? Behaviour is the language of the… Well, I wrote that, the attachment disordered child.

I wrote that a long time ago. I wouldn’t call any child attachment disordered anymore. You know how language changes over time.

Let’s say behaviour is the language of the traumatised child. It’s just about as bad calling them traumatised, I think. Behaviour is the language of the child.

They never had the opportunity to fully develop their language and their capacity to express what’s going on for them because their parents were finding life really hard and were often distracted from the task of parenting them, including sitting with them, speaking their mind, saying what the child might have been feeling or what their intentions or motivations, what their experience was, encouraging them to use their words, all of those things. It’s probably, you know, the language of the traumatised child. You lose so much.

You lose so much detail in that. Those sorts of statements rely on a lot of background knowledge, I think, but they’re good to get people to start thinking about what’s going on for the children. So, how do we respond to a child who is anxious, is self-doubting, is experiencing grief, loss, sadness, feelings of abandonment, feelings of not being good enough? How do we respond to that? The children come back having experienced something, and that’s what we’ve been talking about so far.

They come back and they’re experiencing something. They need to express themselves in some way. They end up expressing themselves through their behaviour more often than we would like because they don’t necessarily have the words that they can put to their experience.

So, they need adults to do that. So, they need the adult whose care they’re returning to, to be able to acknowledge that it’s really sad not being able to live with Mummy and Daddy. Sometimes we think that we’ve done the wrong thing, and that’s why we can’t live with Mummy and Daddy.

But Mummy and Daddy just find life really, really hard and aren’t able to care for you at this time. You love going to see Mummy and Daddy. You get lots of presents.

You have an awesome time. It’s hard to know when you’ll see them again. Mum and Dad are your favourite people in the world. I use that a lot. I often acknowledge that birth parents are the children’s favourite, and I’ve never had one say no.