The content of this post is drawn from my self-paced learning module on the topic of Behaviour as Communication. It was developed for carers of children recovering from early relational trauma that necessitated placement away from home. The complete module can be accessed here. I have included a sample of the content of the module, below. I anticipate that it would take less than one hour to work through the full module. You can purchase a PDF version of this and other self-paced learning modules here.

Children learn to communicate with words in a care environment where their caregivers:

1. Acknowledge their attempts at communication,

2. Speak the words that go with the child’s experience, and

3. Use words to communicate about their experience.

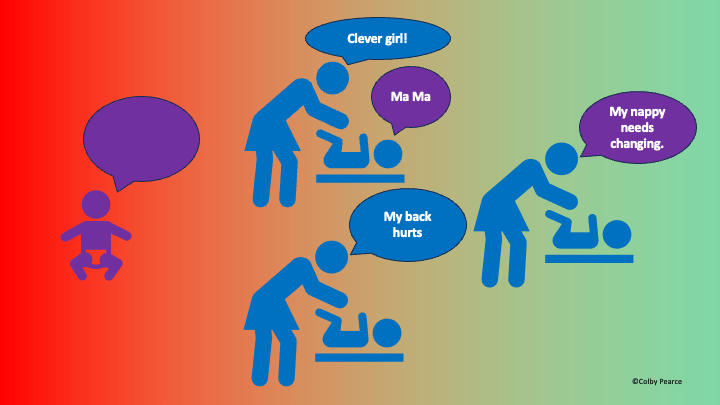

Regarding the first of these, children learn words in a caregiving environment where, in amongst their babble, their caregivers respond with joy and encouragement when they babble something approximating a word. For example, think about the reaction of the mother when their infant first babbles “Ma” in a conventional nurturing care environment. The mother communicates joy and encouragement to the infant. Through the emotional connection that is in place in such moments, the infant experiences a corresponding positive emotion that reinforces their vocalisation of “Ma” when orienting to their mother. As time passes, the infant babbles other approximations of words and is similarly acknowledged and reinforced for those vocalisations over others that do not sound like words to their parent. In this way, the infant begins to express sounds that lead to a response from their parents over sounds that do not.

In addition, in a conventional nurturing care environment parents can be observed to speak to their infant with ‘their voice’. That is, the parent says out loud what their infant is believed to be thinking or feeling, or what they need from the parent. If you are unsure of what I am talking about and have a pet, think about the way in which you speak to them. Through many such interactions, the infant begins to learn what words go with their experience and needs. When able to do so, the infant uses these words and, in conventional circumstances, is acknowledged with joy and pride at having done so, thus increasing the likelihood that they will use their words again.

Further, in a conventional nurturing care environment, the infant observes their parents using language to communicate about their experiences and their needs. In such an environment, the infant learns to use words to communicate about their experiences and needs via parental modelling.

In combination, these three aspects of the infant’s care environment support the development of language to communicate, and its use.

If we then turn our minds to children and young people who are recovering from a tough start to life, what then for their language development and use? When parents struggle significantly in the caregiving role due to their own mental health difficulties, substance abuse issues, relationship difficulties, and/or inadequate parenting knowledge, it is clear to see that the language expression of children and young people who come from that environment is likely to be limited. Put simply, due to inadequate acknowledgement of, and responsiveness to, their attempts to communicate with words, these infants grow with both a reduced vocabulary to express their experiences and needs through words, and less motivation to use them. Rather, they rely overmuch on gestures to communicate, and their behaviour can often be seen to mimic those first behavioural strategies to secure a caregiving response, namely the cry and the social smile. They can be described as overly emotionally demonstrative, though with a restricted range of affect, overly charming, or alternate between the two. These behavioural strategies serve to regulate caregiver engagement and responsiveness. They often communicate that the child or young person has a need that they are preoccupied with, or that they are feeling unsafe. Unfortunately, for the older child they are rarely seen as such by adult caretakers, leaving them feeling chronically misunderstood. This compounds a range of problems experienced by children and young people recovering from a tough start to life, and adults who interact with them in a caregiving role.

Children and young people who are recovering from a tough start to life benefit from the caregiving adults in their life seeing their behaviour as having communicative intent and reflecting their experience and needs. As occurs in conventional nurturing care environments, they need adult caretakers to communicate understanding of their experience and needs through their own words and actions.