In a recent interview with Catherine Knibbs on The Secure Start Podcast, as part of my ‘question without notice’ segment I was asked what we are not doing for, or getting right, with our boys. This followed on from a discussion about the Netflix series, Adolescence, in the broader context of my interview of Cath about online harms our young people are exposed to. This led to the attached excerpt from the podcast, in which we both wrestled with this complex, nuanced, and highly important question, and the broader question of how we address societal concerns about intimate partner and sexual violence committed by men. I hope you like it.

Watch here:

Transcript:

So, my question to you then, Colby, would be, so what, how do I phrase this, so what is it that we’re not doing, and the reason I’m asking you is because you are a man and I am not. I have lived in environments, certainly within the army, where there’s a lot of male, masculinity, and a lot of male attitudes, and I’ve raised two boys, but I am not a male, so I cannot talk from that perspective. What do you think we’re not doing, we’re not getting right? I think to answer your question would probably take the time of another of our podcasts, but where does one start? I think, look, I think we’re failing our boys in so many ways, as a general opening statement.

I think that in our society, my wife and I often talk about having three boys of our own, we’re worried about the way society is going to be for them. I think society has moved to one, to a place of accountability, so men need to be accountable for some of the problematic behaviours that do exist in our society. Men need to understand, for example, that the dynamics of intimate partner violence and consent in sexual matters, our young men need to know all that.

But our young men need, we’re not proud, I don’t think we’re proud of our young men as a society. I think where we’re failing them is that the messages are too much focused, a bit like what you’ve been talking about, not so much outliers, because the rates of domestic or intimate partner violence in our communities, for example, are not insignificant. So I wouldn’t necessarily call it an outlier, it is a significant problem in our community.

However, not all men, the vast majority of men are not perpetrators of intimate partner violence, are not perpetrators of problematic sexual behaviour towards their partners. And I don’t think our boys get that message. They get the message that we’re worried about them, we’re worried about their capacity to do harm.

They don’t get the message so much that we’re proud of their achievements, that we’re even proud of the differences between what a person, what a male gendered person can contribute in all aspects of society and celebrating the distinctions between masculinity and femininity. Sorry, Cath, you did ask the question. It could be a very long answer.

It’s a complicated question. I guess it’s like everything else, nuanced. It is very nuanced.

Multi-faceted. I think, if I really would sum it up, it was a question without notice, but that’s okay, because I love questions. I always promise I’m being able to answer any question put to me.

I would put it like this. Our boys are exposed from a relatively young age to a lot of concern about masculinity as such, perhaps. Yeah.

I think masculinity has become conflated with issues like intimate partner violence and sexual violence. And so the message that they have been given is that to be a man is to be a problem. To be masculine is a problem.

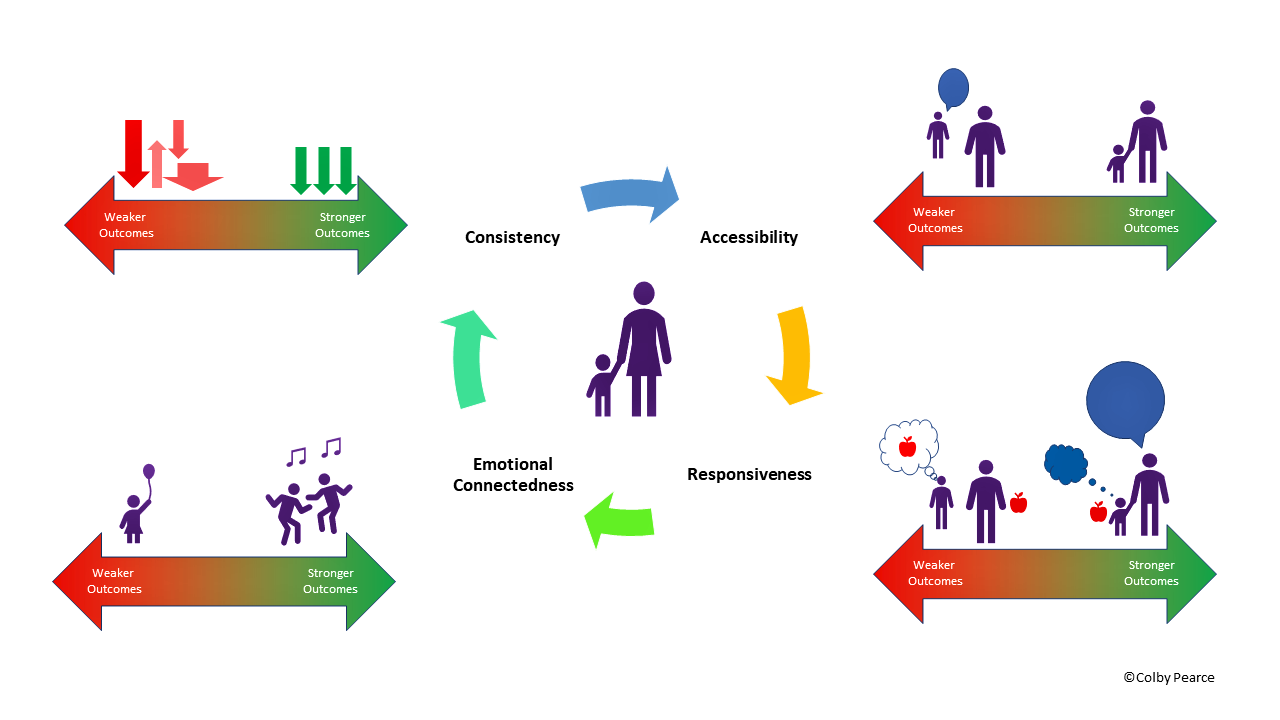

Absolutely, yeah. The problem with that is what we know from attachment, which is if you marginalise people, if you make people feel marginalised in society, in community, then normal social rules and mores, the expectations of others, have less influence over how they go about approaching life and relationships. They withdraw psychologically as a defence against being shamed.

So I think, to sum up my broader views about this topic, I would say, to the extent that we have marginalised males or made them feel bad and inadequate for the behaviour of a proportion of males, we have, in fact, contributed to an outcome where we will continue to see problematic male behaviour, problematic behaviours amongst males in our community, and we may even see growth in those behaviours of concern in circumstances where the people who are calling out the behaviour would say, well, no, that’s not our intent. Our intent is actually to promote accountability and informed reflection by men about the harms they could potentially commit, so that they can approach life in a much more self-aware way and not commit problematic behaviours. And my concern would be that you’ll never get to that point if you start from a place of it’s a problem being male.

I might change one word in that, because the thing that I’ve found, Colby, is it’s you’re the problem. So it’s not being a male is a problem, it’s you are the problem. And for me, to reflect something that a child said in my office, and I’ve said this out on social media a number of times, he was asking a question actually about approaching a woman and said, I’m not going to bother because I don’t want to be called a rapist.

And I went, wow, if that’s the attitude and that’s the fear that young males are holding, and some of it will be conscious and some of it will be unconscious, if that’s what we have done as a society is create this feeling that you are the problem, it is no wonder that there is a retaliatory response at the moment. Because I think, and I’m going to quote my friend here actually, who I’m going to suggest you talk to at some point as well, Lisa Edison, who’s created shame containment theory. And she talks about shame containment is all about you, you contain your shame.

But what we know about shame from many, many years of the research is shame seeps out, and it comes out as rage, and it comes out as aggression, and it comes out. And if we are continually pointing the finger that you being male are the problem, then this contained shame is going to be uncontained and uncontained shame is that really primal aggression that comes from a place of, well, I might as well anyway, if that’s you. And it’s kind of people’s opinions, isn’t it, I guess? Yeah, again, not to not to be meaning to be repetitive.

And by the way, I’m always interested in suggestions for interesting people to speak to. I do I do think that the very social ills that people are trying to address here are likely to be maintained or even worsened in circumstances where it is a shame to be male. I’m feeling incredibly sad, deep down at the moment, as we’re talking about this, I really, really feel incredibly sad for the men who are emerging, and the males yet to be men, I really worry in terms of absolutely, we need to address violent behaviour.

But also, we need to understand where violent behaviour comes from. And I think what we have done is what I call the finger pointing exercise, and it has never worked in society. And I just wanted to acknowledge on behalf of those men, I feel incredibly sad that we have done this.

Yeah, and we society. So I think, I think if we just bring together a number of threads of our conversation, the conversation, it is the case that when a problem arises, our society tends to focus too much on the behaviour of concern. And too little on the reasons why those behaviours exist.

And that inordinate focus on the behaviour of concern would, in my view, maintain and perhaps exacerbate the behaviour or increase the prevalence of the behaviour. Yeah, so the very response is, is a significant part of the problem.