Attachment is an important consideration in decisions that are made in Child Protection. Attachment security is an aspirational goal for children and young people who could not be safely cared for at home with their birth family. Though this is a worthy goal, it’s application is vexed in consideration of:

· the fact that children can (and generally do) form multiple attachment relationships; and

· the difference between attachment relationship and attachment style (or relative security).

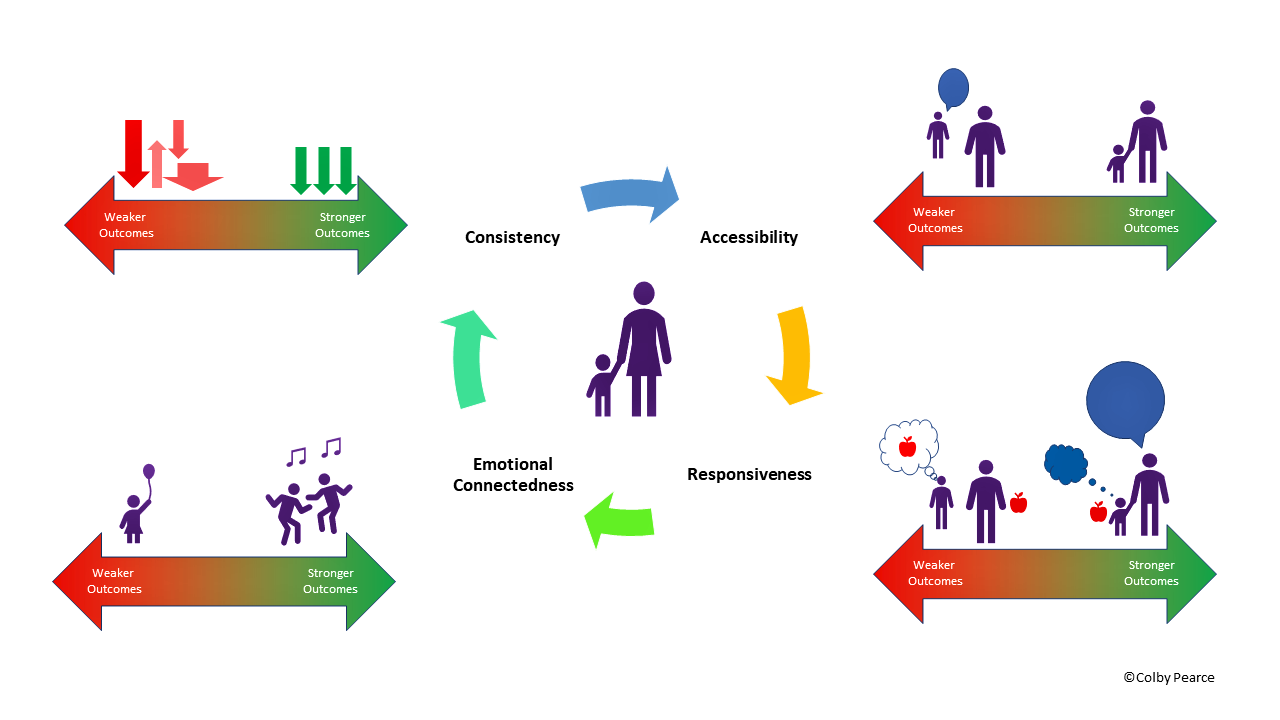

Children and young people form attachments to caregivers who provide physical and emotional care, have continuity and consistency in their life, and an emotional investment in their life (Howes and Spieker, 2016). We refer to these people at ‘attachment figures’. Children can form different attachment relationships to different attachment figures, depending on their experience of care from them. As to which attachment relationships are most influential over a child’s overall attachment style, the evidence favours an integrative formulation, whereby a child’s relative attachment security (and associated social and emotional development and approach to life and relationships) is best predicted by their network of attachment relationships rather than their attachment to any single attachment figure alone (Howes and Spieker, 2016).

In consideration of the above and my own experience observing, thinking about, and writing about attachment for thirty years, it is helpful to think about attachment style as falling on a spectrum of attachment security (hence my reference to “relative security”); from secure at one end of the spectrum to disordered at the other end. Where a child or young person predominantly sits on this spectrum depends on the network of attachment relationships they have, and what type of attachment relationship they have with each of their attachment figures. It has also been my observation that overall attachment style (or relative security) is not fixed, but rather is best thought of as dependent their historical and contemporary experiences of relatedness to attachment figures, and their broader relational world.

What underpins attachment style are a set of (typically) unconscious beliefs about self, other and world. They are variously referred to in the psychological literature as ‘internal working models’, ‘core beliefs’, or ‘schema’. I favour the term ‘attachment representations’. These beliefs are considered to develop in the context of attachment experiences and influence a child or young person’s approach to life and relationships. At the ‘secure’ end of the attachment spectrum these beliefs that influence the child or young person’s approach to life and relationships are typically optimistic, and are reflected in positive adjustment. At the disordered end these beliefs about self, other, and world are very negative and are reflected in significant maladjustment.

How a child predominantly approaches life and relationships reflects their underlying relative security and associated attachment beliefs. However, children are complex, just as we all are. Like us, they don’t just hold beliefs associated with their predominant relative security. They can approach life and relationships under the influence of beliefs at either end of the attachment spectrum, and everywhere in between, depending on their historical and contemporary attachment and relational experiences.

For example, many, if not most, adults who read this opinion will mostly approach life and relationships under the influence of relatively positive attachment beliefs. But something can happen in their life and they can move very easily to the ‘disordered’ end of the spectrum. I observed this while training sector professionals during the covid pandemic, where most adults were able to reflect that in April 2020 they approached life under the influence of beliefs that they were weak and vulnerable, others were a threat, and the world was unsafe.

Turning to a child in out-of-home care, it is possible for them to have a maladaptive attachment to a parent, and relatively more functional attachments to other significant adults in their life, including their other parent, grandparents, their foster mother, familiar school staff, their siblings, and even their therapist. Their overall attachment style will be heavily influenced by their attachment to their parent, but also their relational experiences and associated attachments to other adults who provide (or have provided) physical and emotional care, have continuity and consistency in their life, and an emotional investment in their life. Conceivably, the more positive attachment experiences the child able to have, the greater their relative security and a relatively functional approach to life and relationships.

In terms of the goal of ‘attachment security’, it is worth noting the general finding of research using the Strange Situation paradigm that approximately 60% of young children in western countries have a secure attachment to their mother. In my opinion, this much overlooked research finding is cause for tempering our expectations for those children who could not safely be cared for at home with their birth family.

A more realistic goal, in my opinion, is to facilitate as many positive relationships and relational experiences as possible for children in out-of-home care, in anticipation of this strengthening the influence of secure attachment representations over their approach to life and relationships.

Further, it is my observation and opinion that a much overlooked way of strengthening a child or young person’s relative security is to repair their relationship with their birth parents/family. Relational repair is conceived to have the effect of reducing the negative impact on overall attachment style and relative security of the relationship where harm occurred, and support the development of functional new attachment relationships.

This should be our position when making decisions about contact with birth family for children and young people who could not be safely cared for at home; that the key to future attachment security is repair of the relationships where harm occurred.

References:

Howes, C and Spieker, Attachment Relationships in the Context of Multiple Caregivers. In Cassidy, J & Shaver, P.R. Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research and Clinical Applications, Guildford Press, London, 2016

Pearce, C.M. (2016) A Short Introduction to Attachment and Attachment Disorder (Second Edition). London, Jessica Kingsley Publishers

Pearce, C.M (2012). Repairing Attachments. BACP Children and Young People, December, 28-32

Pearce, C.M. (2010). An Integration of Theory, Science and Reflective Clinical Practice in the Care and Management of Attachment-Disordered Children – A Triple A Approach. Educational and Child Psychology (Special Issue on Attachment), 27 (3): 73-86