In this video I share my thoughts about the need to broaden the much used maxim in out-of-home care circles, from “respond to the need” to “respond to the reason for the behaviour”. My views are shaped by my observation that adults with a caring concern for children and young people who cannot safely be cared for at home often struggle to identify the “need” that gives rise to the behaviour. A better approach, in my opinion, is to have a good explanatory model that guides therapeutic responses.

The video is intended to be of most interest to those who interact with children and young people who are recovering from a tough start to life in care and professional roles. For more information about other aspects of my work, I refer you to the links below and, in particular, the self-paced learning modules on the Secure Start website.

Disclaimer: While great care is taken to ensure that the information in this audio/video is applicable to childhood trauma and based on sound psychological science, it may not suit the individual circumstances of all viewers. If you have any concerns about applicability to your circumstances, please consult a qualified professional near to you.

See transcript below.

Transcript:

Responding to the need instead of the behaviour has long been a maxim of our work with children and young people who cannot be safely cared for at home and are recovering from a tough start to life. But I also think that we need to be turning our minds to the reasons for the behaviour. So those of you who are familiar with my work would know that I use the following statement, which is trauma-informed practice is less about devising strategies to address behaviours of concern and more about responding to the reasons for them.

I found that people sometimes struggle, caregivers in various roles who have a caring interest in our children and young people, have at times struggled with identifying what is the need that gives rise to the behaviour. As they also do with identifying triggers, what was the trigger for the behaviour. But in terms of responding to the reason for the behaviour, I think that that process can be assisted by having a good conceptual and theoretical model that provides a good explanation for what is driving behaviours of concern that we see in this group of children and young people.

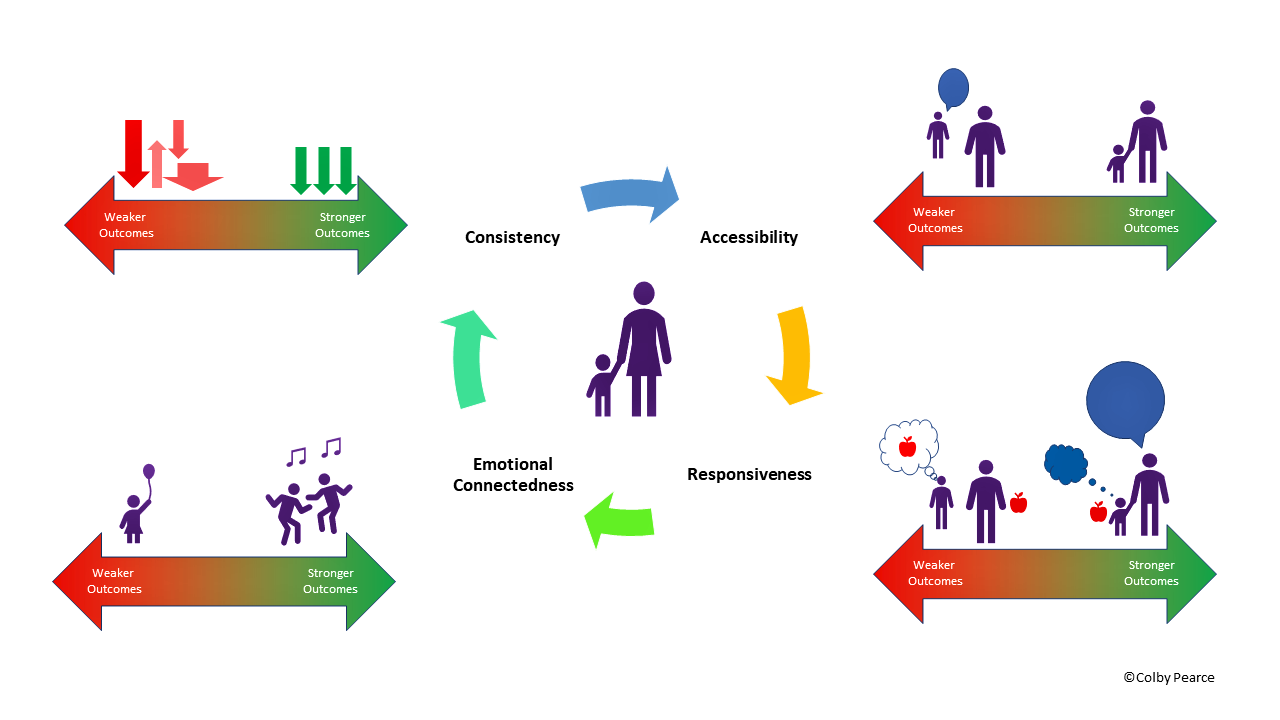

Again, people who are familiar with my work would know that I use the AAA model, a model that was first published 15, 16 years ago, 15 years ago. AAA model is a model that I developed in reflecting upon my experience of working in the child protection and out-of-home care sectors and particularly working with children and young people who couldn’t safely be cared for at home. The three A’s refer to attachment, arousal and accessibility to needs provision.

So, people who are probably watching this video would know what I’m talking about when I talk about attachment. But in terms of the AAA model, what I’m particularly talking about is the working model or what I refer to as attachment representations. These are beliefs often held subconsciously or typically held subconsciously about self, other and the world.

They play a really important role and have a significant influence over the way in which a the reasons behind behaviours of concern. The second A refers to arousal and this really refers to how fast or how activated their nervous system is, how fast their motor runs. And the combination of attachment representation and arousal.

So, what we often see in our children is negative beliefs about self, other and world combined with high levels of arousal, which is a clear recipe for anxiety and anxiety-based responding. So, the fight, flight, freeze response, controlling, aggressive, destructive, running, hiding, hyperactive, withdrawing, shutting down, avoiding type behaviours. So, in terms of responding to the reason for the behaviour, what we will be doing is responding to those anxiety-based behaviours by reducing anxiety, for example.

The third A refers to accessibility to needs provision and that is what I call it that because what I’m referring to there is what has a child or young person learned about how to get their needs met, including about the accessibility and responsiveness of adults in a caregiving role. So, our children are typically very demanding, but they can also take matters relating to needs provision into their own hands inordinately. And so, what is of concern here is their prior learning and that is often maintained, but they’re learning about how you get your needs met.

And their learning tends to be you cannot always rely on adults in a caregiving role to respond to your needs. You need to control and regulate those adults or control and regulate access to needs provision. So, if we’re going to respond to the reasons for the behaviour as well as the behaviour, we need to be responding to that prior learning.

So, what we need to be doing is making it really hard for children and young people to maintain those internal working models or attachment beliefs, attachment representations that they are bad and unlovable, that adults are mean and nasty and uncaring and that the world is an inherently unsafe and threatening place. We need to be slowing their motor. We need to be calming them down.

And with those two things together, we need to be turning our mind to how we reduce their anxiety and we need to be facilitating new learning that their needs are understood and important and will be responded to by adults in a caregiving role through conventional approaches to parenting and relating. So, based on the AAA model, a useful reflective process to go through is to ask yourself, if the child could or would, how would they describe themselves, other people and their world? Your answer to those questions should inform the actions that you take. We need to deploy relational connection and relational behaviours that make it really hard for our children and young people to continue to maintain very negative beliefs about themselves, other people and their world.

You also should reflect on how fast their motor is running or might be running, how activated their nervous system is and be turning your mind to ways to calm their nervous system. And you should finally also be turning your mind to what has the child learned about access to needs provision and the accessibility and responsiveness to their needs of adults in a caregiving role. And you need to be turning your mind to what you can do to facilitate more positive learnings and understandings for the child and make it really hard for them to maintain their prior learning, high arousal levels and disordered attachment beliefs going forwards.

Just finally, those of you who are familiar with my work would be familiar with the care curricula, which encapsulates not only content and theory that helps people understand the experience of children and young people who are recovering from a tough start to life and cannot safely be cared for at home for a period of time. But it also includes a range of strategies that can be deployed in the home or in the classroom that address these three critical impacts of early trauma for children and young people, these impacts on attachment, on central nervous system functioning and arousal levels and their learning about access to needs provision.