Children and young people who could not be safely cared for at home by their mum and/or dad are afforded contact with their birth parents where it is safe and appropriate to do so. Contact done well preserves a sense of connection to birth family that helps with emerging identity, and repairs relationships that have suffered harm. In almost thirty years of continuous work in child welfare, it has been my observation that having birth parents positively involved and interested in the life of their children plays an important role in the success of alternate care placements and children’s outcomes more generally.

Nevertheless, many children are reported by their alternate carers to be unsettled after contact with their birth parents, even when professional observers advise that the child seemed fine and the contact seemed to go well. On some occasions their unsettled behaviour is provided as a reason to reduce or even eliminate contact with birth parents, citing that contact is just too triggering for the child and has the potential to jeopardise their placement.

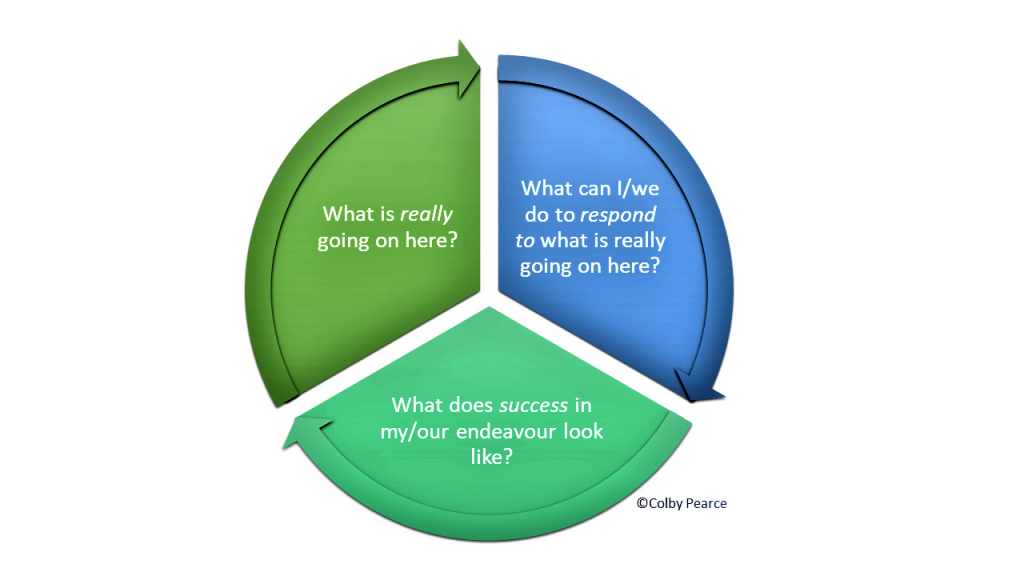

Before reducing or eliminating contact with birth parents it is important to consider what might be triggering for the child about contact, and whether these issues can be addressed.

I have written a lot about four key aspects of caregiving that have a strong influence on relational and developmental outcomes for children: consistency, accessibility, responsiveness, and emotional connectedness; or CARE for short. A child’s experience of parental CARE is almost certainly inadequate in circumstances where children cannot safely be cared for at home by their birth parent(s). Inadequate care is associated with disturbances in attachment, central nervous system functioning, and learning about access to needs provision (Pearce, 2016).

Birth parents may not attend scheduled contact consistently due to their ambivalence towards the agency that removed their children, and/or a lack of resources to attend. When they do attend, they may be distracted by their strong feelings about their children being removed from their care and towards the agency who removed them. This can leave them inconsistently accessible and emotionally-connected to their children during contact. The location and duration of contact may negatively impact the parent’s ability to be responsive to the dependency needs of the children.

In short, contact may perpetuate the child’s experience of inadequate CARE from their parents, leaving them insecure, heightened, and unsure about access to needs provision. Viewed in this way, the trigger for unsettled and demanding behaviour after contact is inadequate opportunities for children and young people to experience parental CARE during (and in relation to) contact.

Before reducing or eliminating contact with birth family it is important to consider what measures can be undertaken to improve children’s experience of parental CARE during and in relation to contact. This involves developing a working alliance with birth parents in consideration of the valuable role they continue to play in the lives of their child. This is necessary to reduce strong parental feelings that can impact negatively on their attendance for contact, and leave them distracted, misattuned, and inconsistently responsive when contact occurs. It also involves supporting parents to attend, and scheduling contact at a time and place and in circumstances where the children have the opportunity to experience their parents as accessible and responsive to their dependency needs. Further, it is important for contact to be fun for parents and children alike, thus supporting experiences of emotional connectedness during contact.

We need to eliminate the potential triggers before eliminating contact. Supporting children’s experience of parental CARE during and in relation to contact represents a necessary starting point.

Where CARE has been inadequate during contact, your child needs you to enrich CARE when they get home.

If you took something useful away from this article, please consider liking it and making a comment. I am interested to read what other behaviours you would like me to turn my mind to.

Reference:

Pearce, C (2016) A Short Introduction to Attachment and Attachment Disorder (Second Edition). London: JKP