I am the father of three boys.

I am the father of three boys.

I am also a Clinical Psychologist with more than sixteen years experience in child and family psychology. I have conducted more than 1000 assessments of children and their parents in child protection and child custody matters. I have appeared as an expert in South Australian Courts on more than two dozen occasions. I have treated more than 500 children. I have written two books and numerous articles about child and adolescent mental health, development and parenting. I have trained more than fifty practising clinical psychologists. I am regularly called upon to conduct teaching and training in relation to the care and management of children.

As is the case in millions of other families around the world, my children test the limits of my patience and endurance. They fight with each other and defy their mother and I. They occasionally get into trouble at school.

At times I have been unreasonably angry with them. I have ranted. I have said things I would rather not have. And, being fed up with them and with myself, I have temporarily withdrawn myself from them.

Recently, I became aware of a series of related beliefs I had been holding for some time. The beliefs went something like this. I am a Clinical Psychologist who specialises in children, families and parenting. I should have a solution for all of my children’s emotional and behavioural foibles. My childen should be well-behaved.

The inevitable result of these beliefs was frustration with my children and myself, regretted words and affective displays, and [temporary] physical and emotional withdrawal at times when they simply proved to be just like the vast majority of children growing up in a [generally] functional family system.

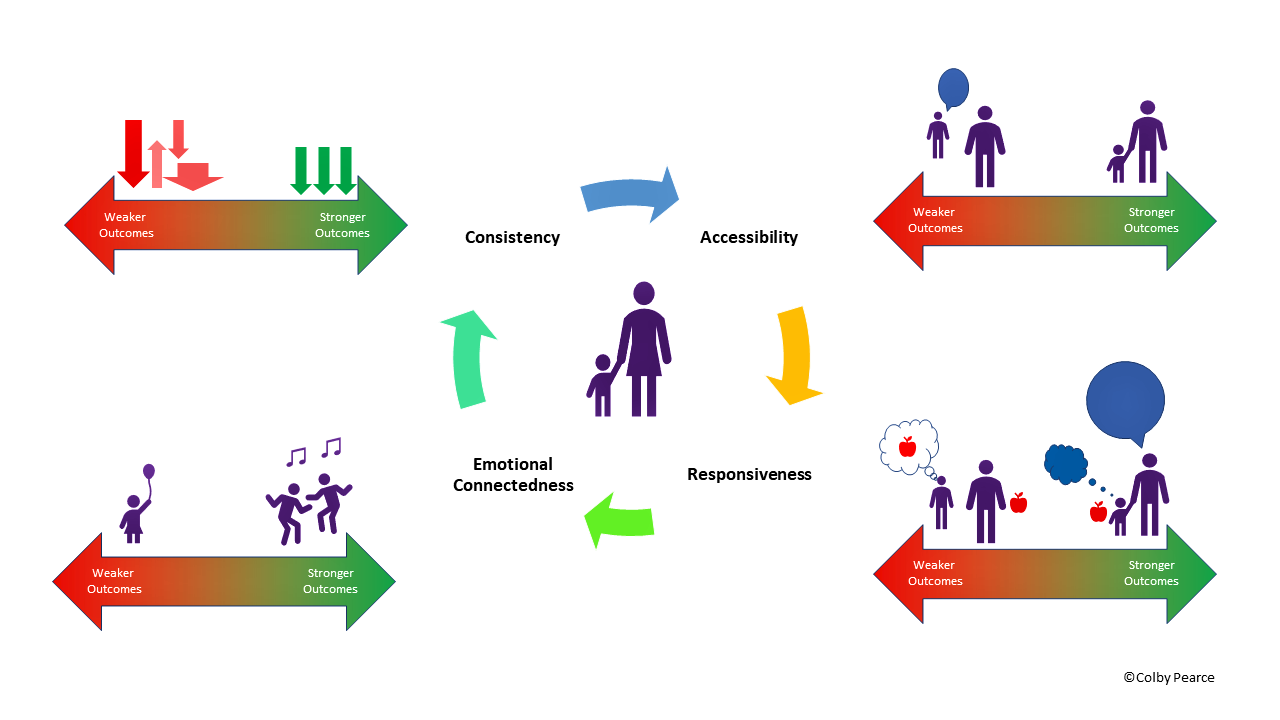

Readers of my books, articles and blogs would know that children thrive on consistency. This extends to consistency of emotional connectedness with their adult caregivers. Children are also emotionally unsettled by heightened affective displays by their parents. Heightened affective displays by parents and associated emotional distress in children make them more prone to behavioural problems and emotional outbursts.

Hence, my belief system was self-defeating.

More functional [and rational] beliefs are that my children do not have to be perfect, nor do I have to be the perfect parent, just because I am a Clinical Psychologist specialising in child and family psychology.

Since adopting these more moderate beliefs I have been better able to maintain a consistent emotional presentation and involvement with my children, including in the face of their difficult and challenging behaviour.

So, give your children and yourself a break. Be moderate in your expectations of yourself as a parent and your children’s adjustment. It is in their best interests, and your own!