They blame themself

For me building self-worth is a critical task when reflecting on the care requirements of children and young people who are recovering from a tough start to life. Self-worth is one of the main casualties of early trauma and loss of connection to birth parents. Children and young people who are unable to be safely cared for by mum and/or dad are often spoken about as blaming themselves, as opposed to their parents, for their circumstances. While nothing could be further from the truth, when reflecting on their circumstances these children and young people express such self-blaming beliefs as:

- I was not good enough.

- I was not loveable enough.

- I deserved what happened because of my behaviour.

- I deserved what happened because I am bad.

Rarely, do they blame their parents for what happened.

It doesn’t matter

These beliefs have an enduring negative effect on the child or young person’s sense of self and the manner in which they approach life and relationships. Pre-school and primary-school aged children may compulsively seek reassurance that they are lovable and deserving of care. They can be very demanding, overwhelm caregiving efforts, and have their unhelpful beliefs reinforced. Older children may be heard saying:

- It doesn’t matter.

- I don’t care.

- Why do you care so much?

What they are really saying is that they do not matter, and that they do not really care what happens to them. These beliefs are at the bottom of a young person’s engagement in self-injurious and self-defeating behaviours, including:

- Self-harm and suicidal behaviour.

- Precocious substance exposure and misuse.

- Precocious sexual exposure and exploitation.

- Poor school attendance and performance.

- Rejection of care (also known as “Blocked Care”).

- Criminality.

My decisions and actions matter.

I matter!

In contrast, children and young people who have a healthy sense of self-worth seem to make more self-promoting decisions than those with low self-worth.

Healthy self-worth grows in relationships.

A healthy sense of self-worth develops in the context of the relationships between the child or young person and adults who care for them. Some relationships are more influential than others, whereby the child’s primary caregivers have the greatest influence. Nevertheless, other adults who play a significant caregiving role (eg grandparents, aunts and uncles, early childhood educators, teachers) also influence the child’s emerging sense of self-worth. As time passes, peer relationships also play a key role in a child’s emerging sense of self-worth.

I am worthy of care!

Every Caregiving interaction matters!

So, what is it about relationships between a child or young person and the significant adults in their life that builds their self-worth? The interactions between the child or young person and caregiving adults is particularly important. What we are looking for, here, are interactions that support the child or young person’s experience:

- That their experience is understood and real.

- That their needs are understood and important.

- That they are worthy of care.

Children and young people who are recovering from a tough start to life are likely to have experienced these aspects of relating to a caregiving adult inconsistently or inadequately. At best, this leaves them with questions about their self-worth and deservedness of care, which, in turn often results in compulsive testing of adults which eventually has the effect of confirming the negative beliefs associated with low self-worth. At worst, this leaves them already believing in their lack of worth and deservedness.

Make it hard to maintain low-self-worth

The challenge when caring for children and young people who are recovering from a tough start to life is to build a healthy sense of self-worth so that they may approach life and relationships with positive expectations and make self-promoting decisions. We can do this by interacting with them in such a way that challenges their negative beliefs about their self-worth, and supports the development of more optimistic beliefs.

Now, you may think that all you have to do is tell the child or young person that they are loved and deserving of care. Think about how you respond to things people might say about you that you do not believe to be true. It is ok to provide praise and reassurance, but only when the situation makes it more believable. Over the balance of this presentation I will talk about what makes these alternative ideas more believable when spoken by you.

Avoid self-fulfilling prophecies!

Let’s start with how we avoid supporting or reinforcing negative self-worth beliefs among the children and young people in our care. Consider the following.

A child in your care thinks that they are bad.

How are they likely to feel? We anticipate that they might feel angry, or sad, or unlovable, or unwanted, for example.

How is the child who feels sad, angry, unloved, or unwanted likely to behave? We anticipate that they are likely to act out, engage in behaviours that negatively impact themselves and others, or become unsociable.

Here is the most important question: How are we likely to react to the child or young person’s negative emotions and/or challenging behaviours? Typically, we tell them off, and in doing so we confirm the original thought/belief.

Change the narrative.

If we intend to change the child’s or young person’s inner narrative of themselves, we need to respond to their emotions and behaviours in a way that promotes a healthier internal narrative.

Parent intentionally.

This means we need to slow down and consider how we are responding to the child or young person. We need to think about what we are doing. We need to adopt certain beliefs, ourselves, in our approach to the caregiving role. We need to approach the caregiving role under the influence of beliefs that:

- Nobody does anything for no reason.

- Behaviour is a form of communication (and may be the child or young person’s best way of communicating what is happening in their inner world).

Nobody does anything for no reason.

All behaviour is a reaction or response to something happening in our world, whether that be our inner or outer world. We may have a need that wants responding to, or a situation that demands an action from us. We may respond in a particular way because of prior learning and, also, because of the influence of an idea or belief that governs our approach to life and relationships. Whether it is an action or a reaction, behaviour is a response to something.

Our task, as caregivers of children and young people who are recovering from a tough start to life, is to think about and respond to the reason for the behaviour. More about this in a moment.

Behaviour is communication.

If you think about it, you can tell a lot about a person by the way they behave. Behaviour communicates something about the person. The same is true of children and young people. In fact, very young children communicate a lot about their needs and experiences through behaviour and gesture. The reason is, they don’t have the words. When caring for very young children we tend to observe their behaviour and think what’s going on for baby? Whatever answer we come up with guides our actions towards the behaviour thereafter.

Children and young people who are recovering from a tough start to life often do not have the words to communicate about their experience and needs, and continue to communicate disproportionately with gesture long after we would normally expect them to ‘use their words’. I have written about this in a module titled Behaviour as Communication, which can be accessed via the self-paced learning modules on the Secure StartÒ website. When we respond to the behaviour in isolation from the need or experience (reason) for the behaviour we run the risk of the child or young person experiencing themselves as poorly heard or understood, thus reinforcing unhelpful beliefs associated with a low sense of self-worth.

Respond to the reason (as well as the behaviour).

To promote a healthy sense of self-worth, we need to respond to the reason for the behaviour (as well as the behaviour). To do this, when considering a child or young person’s behaviour that requires a response from us, we need to ask ourselves these questions:

What does the child or young person get from engaging in the behaviour? (In Learning Theory this is called the reinforcer.)

What can we do to respond to the reason for the behaviour in such a way that:

- The child feels heard and understood in relation to their experience and needs?

- The behaviour is less likely to occur in future?

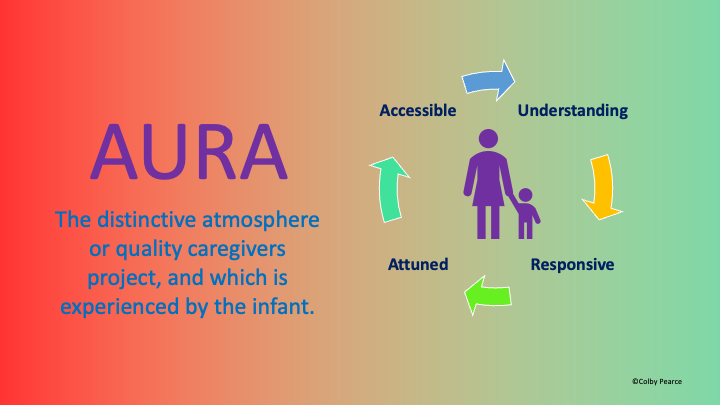

Consider your AURA

This is where we must be mindful of our AURA; that is the unique quality or atmosphere of our home and us when performing the caregiving role.

AURA refers to being:

A: Accessible

U: Understanding

R: Responsive

A: Attuned

Accessible

Being accessible requires being involved and interested in the young person’s life, supporting their access to, and involvement in, activities that are of interest to them. Being accessible is most powerful when it occurs proactively, such as those times that you check in with the young person when they are not looking for you, offer to transport them to their activities, or set aside time to do an activity together. Being accessible supports feelings of worth in the young person, new learning that you are there for them and can be relied upon, and reduced overwhelm at having to manage the world on their own.

Understanding

We can communicate understanding of the inner world of the young person in our care through our words, actions, and emotional expression. Understanding is often referred to as validation; that is, an action that acknowledges the experience of the other person sensitively, accurately, and directly. Validation is reassuring. Validation supports positive beliefs about self and other, and new learning that others can be relied upon.

Responsive

We can support the belief that the young person’s needs and experience are understood, important, and will be responded to by an adult who can be trusted and relied upon by responding to their needs proactively. In so doing, we support the experience that they matter. This is reassuring to the young person and reduces their feelings of overwhelm. If you can anticipate the young person’s need, respond to it proactively.

Attuned

Attunement refers to our congruent emotional response to those of the young person. In moments of attunement the young person feels heard and acknowledged in their experience. Attunement supports feelings of self-worth and trusting connection. Attunement is a biproduct of engagement. We tend to naturally fall into sync with others during shared interaction or activity. Attunement offers opportunities to help the young person better manage their emotions as they follow us back to calm. In support of attunement experiences there needs to be regular engagement with the young person over an activity of interest to them and which will enjoyed by you both.

By following these simple principles embodied in the AURA acronym you will support experiences:

- That their experience is understood and real.

- That their needs are understood and important.

- That they are worthy of care.

A final word. Watch this video about selective attention, self-care, and a child’s self-image: