Watch this video to hear hear me talk about the real reasons for behaviours of concern exhibited by children and young people recovering from a tough start to life. You will hear about three key reflective questions to ask and answer in your own mind about the experience and learning of the child or young person, which will help you better understand their needs and experience, and how to respond therapeutically to them. I have also included an article upon which the video is based, below.

A central pillar of trauma-informed care and practice is to respond to the unmet need that is giving rise to the behaviour.

The reasons for this are (at least) threefold:

- Children express their needs and experiences through behaviour from the first minutes after they are born, and continue to do so throughout their development. In fact, we all do. We just do it less and less as words and speaking replace behavioural expressions. It is entirely normal to express ourselves through our actions and emotions.

- Children who spent time in a very inadequate care environment learn that in order to get attention and a response to their needs they need to make a fuss. Their language development can also be restricted, such that they do not always have the words to express themselves.

- If we don’t respond to the need or experience that gives rise to the behaviour of concern, the child’s needs and experiences may continue to be inconsistently or inadequately met, leaving them feeling and believing that they are undeserving and unworthy, and feeling and believing that us, the adults involved in their care, are uncaring, unresponsive, untrustworthy and, in some instances, unsafe.

A little caveat here. Why “unsafe”? This is because adults who very inadequately responded to their needs in the past may also have been responsible for, or struggled to respond effectively to, the child feeling unsafe. In such circumstances, any adult subsequently involved in the care of the child may make them feel unsafe due to the same processes that occur when for example, we feel nervous in circumstances similar to those where we were previously hurt or frightened in some way.

Moving on. So, if we accept the idea that we must respond to the need or experience that gives rise to the behaviour, how do we know what this is?

In my work I have observed that, though they may accept this pillar of trauma-informed care and practice, adults involved in the care of the deeply hurt child have difficulty identifying what the unmet need or experience actually is.

A consequence of this is that the deeply hurt child continues to experience adults as failing to understand them, and inconsistently responsive to them, which only perpetuates their demanding and demonstrative behaviour, or problematic self-reliance.

Consider taking food without permission, or gorging on it when it is available, for example. This is a big problem in many households providing reparative care to children recovering from a tough start to life. Many a parent will say that the child cannot have been hungry, I give them plenty to eat – and they do. Many then see the behaviour as something that needs to be managed by making it harder for the child to gain access to food.

Unfortunately, this misses the point that the reasons for the behaviour include:

- Reassurance that the child has access to food where, historically, this may not have been the case;

- Anticipating rejection, and uncertainty about future access to food; or even

- That they are hungry.

It follows that successful management of this behaviour does not lie in restricting access to food but, rather, in making it easier for the child to access food and helping them to experience that conflict and disapproval are not the end of a relationship.

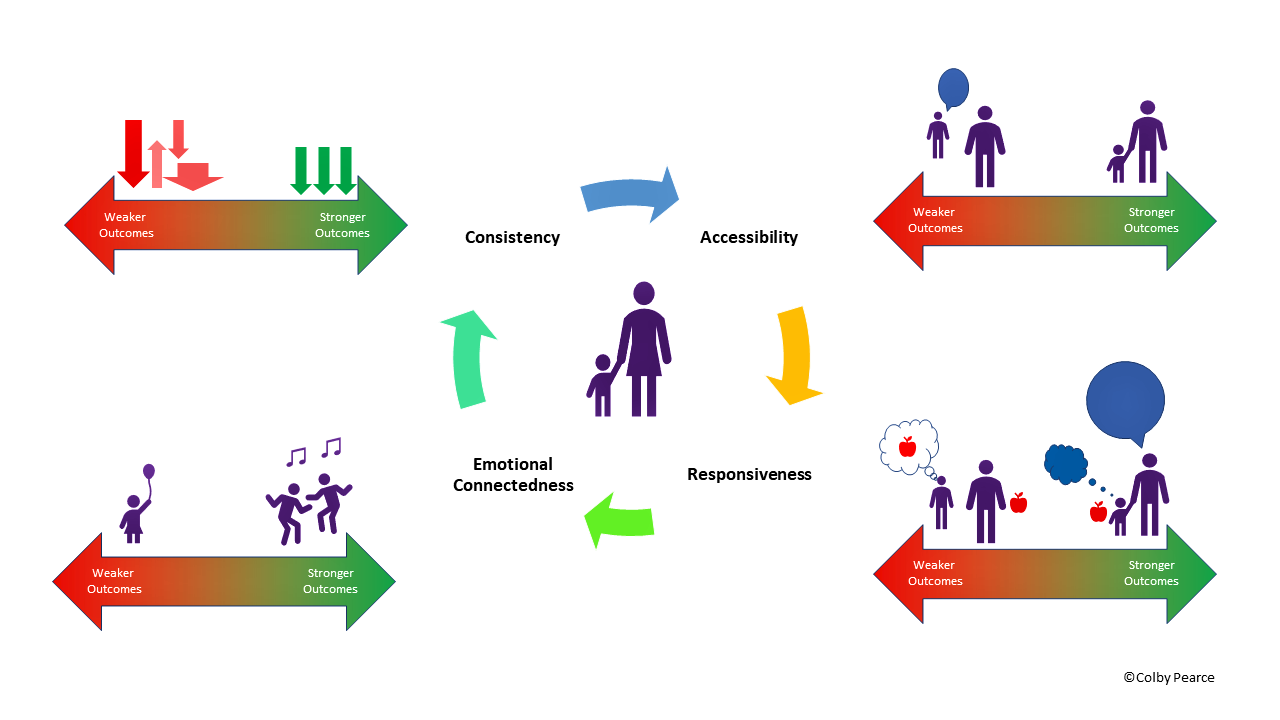

If you are still with me, that’s great! I won’t keep you much longer. It would be hard for me to keep your attention as I go through an exhaustive list of behaviours of concern and the reasons for them, though I could. Rather, I refer you to three simple reflective questions I developed, based on the Triple-A model, to help you come up with some ideas about what common reasons for behaviours of concern are. These questions are:

- If they could or would, how would the child truly describe:

- Themself?

- Others?

- their World?

2. What did the child learn about the accessibility and responsiveness of adults in a caregiving role in their first learning environment(s)?

3. Typically, how activated is the child’s nervous system (aka: How fast does their motor run)?

The answers to these key reflections is often the real reason why the child approaches life and relationships in the way that they do.

You can watch me speak about them in the video in the top left of the screen. You will also find other videos about how to respond to the unmet need and experience of the child in the playlist in the top right. The video about verbalising understanding is likely to be of further use to you, as it deals with an important way we can facilitate verbal expression, as opposed to behavioural expression.

Finally, remember this. If we don’t respond to the reason for the behaviour, the deeply hurt child will struggle to ever fully heal.