Recently, I was invited to deliver training to staff of a local children’s services organisation. I chose to deliver the training on a reflective process for understanding and responding therapeutically to behaviours of concern exhibited by children and young people recovering from a tough start to life. The session was recorded, and I have provided an edited version below.

To get the most out of the training video, I suggest you download the accompanying handout here.

Transcript

Hi, I’m Colby Pearce. Recently, I was asked to deliver training to a local organisation and its staff with no brief about what that training would be about. So I decided to deliver the training on the topic of responding therapeutically to behaviours of concern.

The training takes you through a reflective process with the intention of being able to answer three critical questions. What’s really going on for the child or young person when they exhibit the behaviour? How can we respond therapeutically to the real reasons for their behaviour and how will we know that we’ve made a difference? The training was recorded and the following video is an innocent version of it. It’s probably of most usefulness to practitioners in child protection, foster carers, kinship carers, residential carers and teachers of children and young people recovering from a tough start to life and other professional stakeholders in their life.

I hope you take something positive from the training. There is a handout to go with the training, a link to which I’ve included in the description of this video. If you take something positive from the video, please give it a thumbs up and subscribe to my channel.

Your interest is highly encouraging of me to continue to make high quality content for those who interact with children and young people recovering from a tough start to life in care, professional and other stakeholder roles. I thought I’d talk to you about something that probably comes up a lot in our work. So I thought I’ll talk about behaviour management because carers, foster carers, kinship carers often like to talk about behaviour management.

What should we do about this behaviour or that behaviour? Notwithstanding that probably it is the case that most if not all carers in the sector these days get training that argues perhaps for relying less on conventional behaviour management strategies and more on providing a therapeutic milieu in the home, a trauma-informed milieu. And certainly also in schools there’s conventional behaviour management strategies are used all the time. So I’m intending to make this a bit of a reflective process.

Hopefully you’ve all got pen and paper and handy. What I want you to do in the first instance is I want you to just think of a child or young person who you either care for or working with and on a piece of paper just want you to write down their name. And now what I want you to do is just is to have a bit of a think about a behaviour that you or others are concerned about that that child exhibits, a child or young person exhibits.

So just write down underneath their name a behaviour that is of concern. In terms of responding therapeutically, which is my aim to impart today, responding therapeutically to behaviours of concern. This is really the simple structure that I am going to follow.

It’s part of the care curriculum, a curriculum that I’ve written over a long period of time. The three essential parts of what’s really going on. How can I respond therapeutically to what’s really going on? And how will I know that I’m successful in my endeavours? So how do we know that we’re successful when we intervene or respond in relation to a presenting issue? You should have the name of a child and a behaviour that you or others are concerned about.

The next thing I’d like you to do is answer these three questions about the child. We’ll write an answer to these three questions about the child. First one is if they could or would, how would they truthfully describe themselves, other people and their world? Don’t worry if it’s very negative because that’s common in our children.

How fast is their motor run? That is, how activated do you think their central nervous system is? Does it run really fast? Often kids whose nervous systems run very fast have problems with sleeping, they display high levels of activity and agitation. Although that can be confusing because also kids whose nervous system is under aroused can be impulsive and overly active as well. Sleep is affected, the children seem to have trouble going to sleep, staying asleep, wake up early but seem to function better than you would expect.

On the lack of sleep, are they anxiety prone or prone to tantrums? Their anxiety, proneness and tantrums tend to be associated with the motor running a bit fast. So just write down what you think, how fast you think their motor is running. Do you think it’s normal? Do you think they’re just very laid back and it’s slow? Or maybe they have ADHD.

With ADHD we have an underactive nervous system that is corrected through psychostimulant medication which has the so-called paradoxical effect of them calming down. And the calming down bit is that they’re less impulsive, less prone to trying to seek movement and activity to increase central nervous system arousal and better able to think and concentrate clearly. It’s a trickier one with ADHD because the behaviours you see are not dissimilar to what you see with a highly anxious child.

But it’s really important to discern whether it’s one or the other because it impacts how you might respond to it. The third thing I’d like you to consider is what do they appear to have learnt about how to get their needs met? Remembering that kids learn about adult responsiveness from very young, from infancy. So the sorts of things to be turning your mind to there include, you know, are they pretty relaxed about adults responding to them? Are they really demanding? Can’t let the adult out of this science.

Will ask for things that they don’t even want or need but just to reassure themselves that they have access to needs provision. Remembering that normality and abnormality are differentiated by frequency, intensity and duration. So by which I mean, if you made an exhaustive list of behaviour of concern that children and young people might exhibit, a good proportion of them would be exhibited by most children.

The difference is frequency, intensity and duration. There are a few exceptions like sexualised behaviour, for example, although there is a developmental phase when children are more interested in their reproductive parts. And with engaging with others a little around that.

But not, you know, not to the extent that we see because it’s more exploratory and interest rather than symbolic, for want of a better word, and representative of unlawful things that have happened to them. Well, hopefully you’ve all got something down for that. The figure on the to the right of it, hopefully you can see it in full, is the AAA model.

I’ve been using the AAA model for a long time as in my work as the basis for understanding the internal world of children and young people. It was first published in 2009, then several times since, including in international peer-refereed journals. But it’s meant to be a model that facilitates us having an understanding of what’s going on for our children and young people.

So the first bits where I asked if they could or would, how would the child truthfully describe themselves to other people in their world, that maps onto attachment, particularly in the AAA model, whereby what we’re talking about is the internal working model is a term that you would see commonly in the attachment literature. I use the term attachment representations. Schema, self-schema, core schema are used.

But what we’re really talking about is the core beliefs that a child or a young person has about themselves, other people and their world. And we all have these. And we all have a set of beliefs that we are lovable, capable, deserving, worthy, the adults are kind, understanding, accessible, responsive, and the world is a safe place.

We also have beliefs that the world can be an unsafe place, that we’re weak and vulnerable, and that other people are unsafe. And what we tend to do if you think about attachment as a spectrum, people kind of move along that spectrum based on what’s happening in their life in terms of these attachment representations. So what I would say to you is that our children and young people, they spend a lot of time down the really negative end.

I’m bad, unlovable, unworthy, adults are mean and nasty and uncaring, the world is an unsafe place. And sometimes they’re up the other end, you know, where they’re starting to believe more in themselves than in others. Sometimes they’re up there too much, they’re down the other end.

Whereas most of us, we’re a lot of time up the good end, secure end, but we do sometimes go down the other end. And the best recent example of that was in about March and April of 2020, when suddenly the world became unsafe, other people were unsafe and a threat, potentially threatening, and we were vulnerable and weak. So we all have it within us to go to that darker place.

But our children, when I say our children and young people, or our children, I mean the children that we work with, they spend too much time there. And, I mean, it’s beyond the scope of this presentation to talk exhaustively about attachment, but where they predominantly sit on that spectrum, really negative down one end, really positive up the other end, secure, disordered, where they sit really just depends on things that are happening in their life now, but more so has a lot to do with the kind of relationships that they’ve had in their life, key relationships. Because most of the young people who we work with have experienced relational trauma, they’re kind of prone to being down the negative end more, but we can move them more towards the positive end by facilitating lots of positive experiences of relatedness and repair of damaged relationships.

That’s why we do family contact. So this is attachment, this is the attachment part of it, and the attachment part of the AAA model, as I said, is what would they say about themselves, other people and their world, if they could or would. Remembering that our children don’t always have the language to express this, it’s more experienced and felt.

Anyway, that’s kind of like their thoughts, feelings. The thing about emotions is that emotions are thought to have two components, arousal and valence. So valence just means good or bad, arousal means level of activation of your nervous system.

So when you’re experiencing emotions, your motor runs faster. When you’re experiencing really strong emotions, your motor runs really fast and is in danger of blowing up. So arousal is the second A of the AAA model.

Our children, they tend to get to blow up really easily. A big part of that is that they idle quickly, they’re highly strung by and large, but they also negatively interpret their world through those attachment representations. So they see threat, they see neglect or they see withdrawal of care everywhere, even when it doesn’t exist.

So they’re particularly anxiety prone, our children. Anxiety is most likely to occur when there’s negative, overly negative appraisals of a situation and your motor’s running too fast. So our children, as I said, motor running too fast.

Accessibility to needs provision is an interesting one. So the literature, the child trauma literature is over the time that I’ve been working and before that, well before that, a lot of it was psychoanalytic thought, but probably attachment theory was the predominant theoretical approach to understanding what’s going on for our kids and young people. Then from about the mid-90s, which is when I started my career in DCP, the work of Bruce Perry and others started to be widely known and thought about and integrated.

So we ended up with content and knowledge around central nervous system development, the neurobiology of trauma. In reality, if you distill it all down, what we’re talking about are nervous systems that are not well developed to be thinking through things before acting and overly prone to activating the deeper structures of the brain that result in increased arousal or high levels of arousal. Apart from my early work in DCP, I did a lot of work in inter-country adoption.

In inter-country adoption, children were coming from quite disadvantaged care environments overseas into quite enriched care environments here in Australia, but they would continue to behave as if they were in the old care environment where they were in an orphanage in a third world country where there was a high ratio of kids to adults, so it was really difficult for babies to get their needs responded to in a timely way. So what it prompted me to do is to think a lot about what children learn in their first days about how to get their needs met. In the AAA model, it’s dealing with the kids’ thoughts, their feelings, so thoughts and feelings, attachment, arousal, and their learning, thoughts, feelings, and learning.

So what we know, probably the best paradigm for understanding what they learn is the operant conditioning paradigm. The operant conditioning paradigm is the paradigm that underpins most, if not all, of what we refer to as conventional behaviour management. So as we’re growing up, we try different behaviours and some behaviours get a response from others, a desirable response from others.

We refer to that as a reinforcer. So a child will do something, they’ll get a desirable response from someone. If they get that response often enough and consistently enough, that behaviour becomes a useful part of their repertoire and they’ll keep doing it.

It’s a bit like when a kid starts school and the teacher says, put your hand up when you need me. Kids have to learn about putting their hands up. If the teacher responds consistently enough, the kids will quickly learn that that’s how you get the teacher’s attention and they’ll put their hand up.

Now they’re not the kids that we’re seeing. I did an international survey a few years back, put a whole great big exhaustive list in of behaviours and potential behaviours of concern. I got responses from kinship carers and foster carers from western countries around the world.

On it they could put a checkmark next to as many behaviours of concern that they were observing in their home. And the most commonly reported was how demanding the children are. Can’t speak on the phone, can’t have someone over for a coffee, can’t even go to the toilet or have a shower without them trying to maintain connection.

We certainly do have kids who alternate between overly demanding and overly self-reliant. By self-reliant, I’m talking about things like, you know, getting up in the night and raiding the fridge in the cupboards, not even getting up in the night, just doing that during the day. But more often than not, they’re just highly demanding.

So this is the AAA model, the way they think, the way they feel and what they’ve learned about how to get your needs met. So moving on to the step number four, with regard to that behaviour of concern that you wrote down for the particular child a little bit earlier, and thinking about your answer to those previous three questions. How would they describe themselves? How fast is their motor running? What did they learn about how to get their needs met? I want you to consider what might be the real reason for the behaviour of concern.

Write that down. What do you think is the real reasons or reasons for the behaviour? And as it says on the handout, if you’re not quite sure, just think about those three further questions. What’s the purpose? Does the behaviour serve? What is their intention when engaged in the behaviour? What needs does the behaviour meet? The behaviour of concern may be that they’re quite demanding.

And as I said, that’s the most common complaint or observation of carers in this space. The conventional behaviour management strategy is to ignore them, take away the reinforcer. And it works.

It works if that behaviour arose under conditions of consistent reinforcement. Now, our children were not raised under the conditions of consistent reinforcement. In real life, in our life, with our children, they’re not responsive to the carer’s attempts to extinguish the behaviour by not responding to it.

They’ll just keep trying and trying and trying and trying and trying, because they’ve learned that if you keep going, eventually you’ll get what you need. And eventually they get what they need. One of the most difficult ones has been in younger children.

The advice is to ignore it. How do you ignore a younger child headbanging? If they got a consistent response to headbanging, you wouldn’t have to ignore it much if you went down that path. I would never recommend it before they stopped, but our kids wouldn’t do that.

They would just keep going and going and going, and often enough do. So I would say you should be turning your mind to the way the child thinks, the way the child feels, and what the child has learned when you’re thinking about why the behaviour of concern is presenting itself. The other part of the operant conditioning paradigm that translates into conventional behaviour management is rewarding the good behaviour.

Our children, if you try to go down such a path, they doubt that people will actually give them the reward, because they’ve learned that they’re unworthy, undeserving, that adults are unpredictable, unreliable. So often enough, they just go, if I can get that reward, give it to me now. No, you have to pull up your socks, you have to do these behaviours that are part of our behaviour management plan.

Well, you’re not going to give it to me anyway. They may not say this. Often enough, our children don’t say these things, but they definitely think it, and if you’re interacting with them and you go, well, I think you were probably thinking they wouldn’t give it to you anyway, and they just come to life, and their eyes open, and they’re like, yes, they wouldn’t have given it, because they find it difficult and maybe even are unmotivated to really say what’s going on in their head and their heart.

We know they find it difficult because, depending on how long they’re in an impoverished early environment, early language learning is impacted, and that’s why a lot of the interventions that I do and support are about supporting expressive language development, because one of our problems is our kids express themselves through their behaviours rather than their words. Often enough, that’s because they either don’t have the words or don’t think adults will listen to them anyway. So, we’ve got to build confidence so adults understand their words, and we’ve got to support them to develop their words.

Punishment, of course, that really sets them off. I knew you were this, that, and the other, and, you know, I’m just bad, and nobody loves me, and I’m unlovable, and I don’t deserve anything. Often our kids, if you give, if you say to them, you choose your punishment, they’ll choose something way worse than the adults had in mind.

So, that’s a clue to what’s going on in their head and in their heart. So, trauma-informed care and practice is less about implementing conventional behaviour management strategies and more about responding therapeutically to the real reasons for the behaviours. So, the next one on the list is, in consideration of all of your previous answers, how do you think this behaviour of concern should be responded to? Write that down.

You may not put much store on what I’m saying and stay still conventional behaviour management, but I would suggest maybe it would be responding with understanding of what’s really going on here. So, now what I want you to do is I want you to write down, now that you’ve identified what you think is the real reason for the behaviour, what you would do, how you would respond to it therapeutically, the actual things that you would do. So, while you’re doing that, if you’re still doing that, it’s okay.

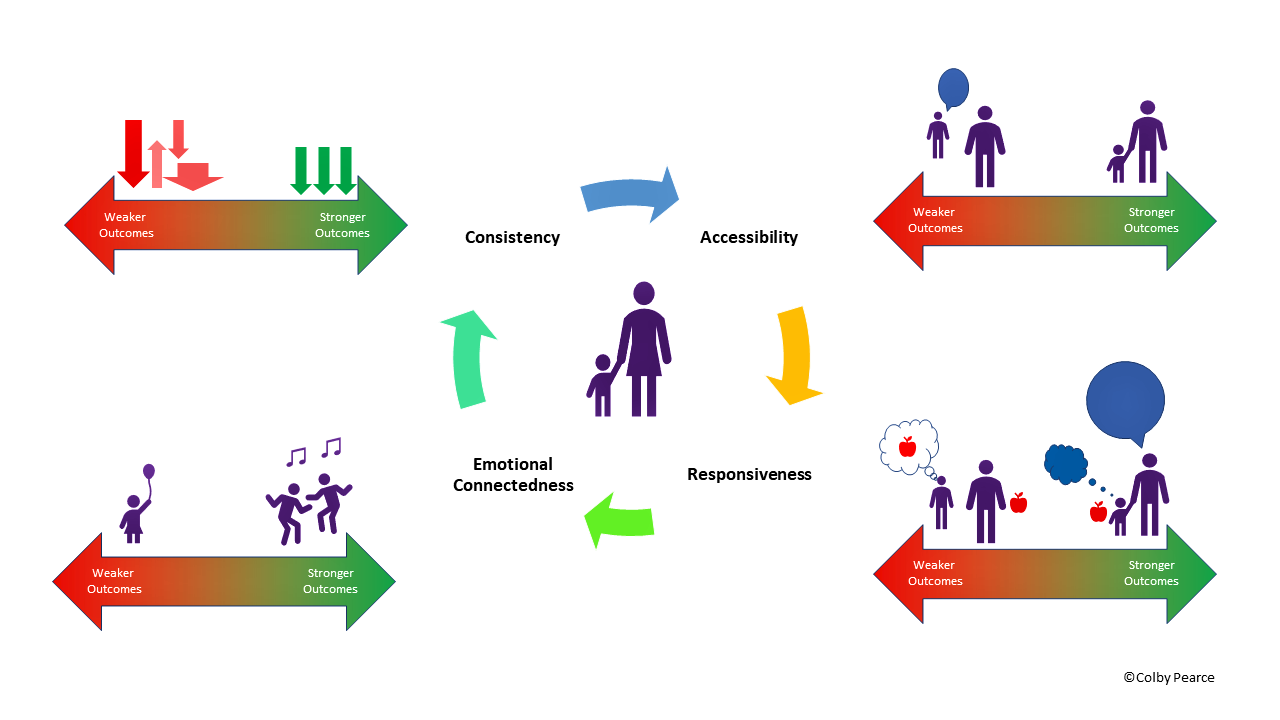

I’ll just, well, I’ve just got a slide up here that represents a model for addressing those three key factors of attachment, arousal and accessibility and needs provision. I like to think in terms of acronyms. Well, acronyms are helpful for people, I’ve found.

Probably the main one I use is CARE. CARE stands for Consistency, Accessibility, Responsiveness and Emotional Connectedness. That’s what’s in my books, for example.

But I like the idea of aura a little bit better, partly because I’m a bit mischievous and in my profession, which is a very serious profession, we shouldn’t be talking about auras too much, but I’m not talking about auras in the metaphysical sense. I’m talking about the actual definition of aura, which is the distinctive atmosphere or quality that a person or a place projects, which is experienced by the young person, their felt experience of us and where they are. And it’s also a handy acronym for what I advocate, that we be accessible.

Being accessible for our kids is reassuring to them. Being proactively accessible is the best way to do it. Being accessible is reassuring, it lowers arousal.

If the carer’s attention is on the child, that supports experiences that they’re a person of worth, that the adult is here and accessible to me. And it provides the basis for changing their learning from, I have to work really hard to control this person to make them respond to me, be there for me and respond to me, to this person, this person is there for me. So accessibility is all about being there, facilitating learning that the adult is there for them, which is reassuring, it lowers arousal and it also supports a more optimistic set of ideas about self, other and world.

Understanding. I often talk about the next three as one, in the sense that we can’t solve all problems in this space, but at least we can respond with understanding in our words, in our actions and in our expressed emotions. And when we do that, the child or young person experiences that we get it.

Not only are we here for them, but we get it, we understand. Often that’s referred to as validation. Validation is like a psychological inoculation against later major mental health concerns.

So our kids benefit from us responding with understanding in our words, in our actions and in our expressed emotions. So the you and or, the strategies that I suggest are that we speak their mind, that we reduce the number of questions that we ask them and rather, if we think we know, if we find ourselves going to ask them a question and we think we know what the answer is, should we give it, we just say the answer. Don’t ask the question.

When we ask our kids questions, they think, oh, another adult that doesn’t understand. Often enough, they think that. When we say the answer, their response is, their experience is, you get it.

I’m a person of worth. I can trust you. And it also helps with developing their expressive language if we do it a lot.

So the you and or is being understanding in our words. The are is responsive. We’re responding proactively to their needs.

Why I say proactively is this distinction. If a child does something and we respond, they only think we responded because they did something to make it so. So they’re not learning anything different than what their historical learning, which is you have to control and regulate adults to get a response and get your needs met.

But when we respond proactively to their needs, when we spend time thinking about the kids and their needs, so we look at this behaviour and we think, well, what’s really going on there with that behaviour? And if we think it’s because they need reassurance that we’re there for them, well, what we’ll do is we’ll make sure that we attend practice with them in sport for sport. If they’re playing sport and make sure we get out to the games. It can be that we just make sure that we touch base with them a couple of more times during the day than we normally would proactively.

I say to our carers, for a few days, just write down all the things they ask of you, or they do to get a need met. Yeah, all the things they ask for and all the things they do to get the needs met. And I’ll say to carers, can you anticipate any of them? Do they always ask for blah, blah, blah after dinner, after tea? Yeah, well, if they always ask for it, don’t wait for them to ask, get in first.

Just do it. When you do that, their experience now is, you just did it without me having to control and regulate you to make it so. Their experience is, you get me.

I’m a person of worth. I can trust and depend on you. What a relief.

So responding proactively to needs supports, as all of these things do, supports moving the kids up towards the secure end of the attachment representation spectrum, lowers arousal and anxiety proneness. Remember, with anxiety, you’re going to see behaviours associated with fight, flight, freeze, right? Controlling, aggressive, destructive, fighting, that’s your fight. Hyperactive, running, running away, exiting the classrooms, for example.

Flight, freeze is just withdrawing, going away in their mind, not responding. Some people talk about form these days as well. But the main things that people see are the fight, flight, freeze type behaviours.

So all of these things, with the aura, lower anxiety proneness and they facilitate a more optimistic learning that adults are there for you and they understand your needs and they will respond to them without you having to push their buttons or pull their strings all the time. And the last letter in aura is A and that’s attunement or affective attunement. Now, attunement is just where you’re in sync with each other emotionally.

Research has been done where they put heart rate monitors on mothers and infants and then during play, what they find is the heart rates vary in sync with each other. So very quickly, the child goes into sync with the mother’s heart rate and vice versa. Heart rate is a sign of arousal or central nervous system activation.

And as I’ve said before, central nervous system activation is the physiological component of emotion. So that’s seen as physiological evidence of emotional connectedness in play or attunement. What attunement does, amongst other things, it’s really good for emotional development, it’s really good for perspective taking, it’s really good for socio-emotional reciprocity down the track and so on.

But at the very least and fundamentally, what it communicates to the child is, I’m here for you. I see you. I feel what you’re feeling.

You are a person of worth. I can be trusted. I care about you.

I’m here for you. The attunement experiences also address all three aspects of that AAA model. My reason for putting up and talking about Aura is all of those elements in Aura address the AAA model.

Now, my next question is, if you respond to the real reason, what would you expect to happen? Write down what you think would happen if you respond to the real reason for the behaviour. There’s two questions that I ask carers. What do you think is going up and how will you know that my intervention has made a difference? So for carers in terms of their care, it is we’re encouraging them to respond more to the reasons and less to just the behaviour of concern.

How will they know that it’s made a difference? And I tell you that that is the hardest question that I ever ask of adults, whether they’re foster and kinship carers, or teachers, or even case managers and social workers like yourselves. We find it very easy to identify behaviours of concern, but what it would look like when there’s an improvement that people tend to find that really hard. It has a bit to do with this.

I’m just going to put an image up. I want you to just look at it and notice what is the first thing that you notice about it. Does that make sense? Notice what you first notice about this image.

When I use that slide in my training, very commonly people just call it out. What stood out to you about that image, that array of maths equations? That’s the most common thing that people notice about it. Aside from, I’m not maths, I hate maths.

We’re problem solvers. We’re programmed that way. Our central nervous system makes us look for problems to solve, or privileges looking for problems.

And this is why it’s a really easy question to answer when I say what are the behaviours of concern? It becomes a really difficult question to answer when I say, how will you know that we’ve been successful in our endeavours? What will you notice that’s changed? Other than, well, the behaviour will be less. It is a problem that our nervous system is very good at focusing on problems, but not so good on noticing that nine out of 10 was right. We’re not good at noticing the things that are going well, because that’s not the way we’re built.

If we’re not noticing them very well, we can get bogged down in the problems of caring for these children. We skew towards looking for problems to solve. That’s just the way we are.

And that can be overwhelming for our carers, and it’s not great for our kids, because our children are very susceptible to the looking-glass self. The looking-glass self is a construct that was first talked about over 100 years ago by a fellow called Charles Horton Cooley, who wrote a book that was published in 1902. But basically, the premise of the looking-glass self is that we see ourselves as we experience other people to see us.

We see ourselves as we experience other people to see us. Now, adults are sophisticated enough to try and influence how other people see them, but kids are not so sophisticated, and teens just start in the process of being more and more sophisticated. So our children are very vulnerable to seeing themselves as we see them.

So they see themselves as a problem more often than not, unless we can also identify some really positive things to look out for and acknowledge. The other problem with our tendency to be problem-focused is this next slide. This is called the nine-dot problem, and your task here is to put your pen on the page at one dot, one of them, and join up all nine dots with four straight lines without taking your pen off the page.

The nine-dot problem was developed by Edward de Bono. The problem focus we have is frustrating. So this rubs off on our kids.

If we’re annoyed, they become agitated as well. So it’s important to know what success in our endeavours look like. Next to step eight, I’ve got the question, how might a child or young person approach life and relationships differently if you respond in the way that you’ve written in step seven? I’m going to put a slide up that you might want to reference.

You might reference it too. And you can also do that last one too, step eight, how might the child or young person approach life and relationships differently when you respond in the way that you proposed at step five and six? And obviously, by having this up, I’m suggesting that you’d be addressing the real reasons for the behaviours as they’re organised under arousal attachment and accessibility. What I’ve tried to do in relation to getting behaviour management right is talk about or get you thinking about what’s really going on, how we can respond therapeutically to what’s really going on, and how will I know that we’re successful in our endeavours, that we’re getting it right.

absolutely loved this

I thought you were talking about my grand daughter to a tee

you are a legend and a awesome help

taking care of my granddaughter that has had a terrible start in life isn’t easy

but I love reading your stuff

long time fan here

Thank you. That is great to read!