In The Zahir, author Paulo Coelho tells the story of two firefighters who take a break from fighting a forest fire by a stream. The face of one of the firefighters is dirty and sooty. The face of the other is comparatively clean. One of the firefighters then washes his face in the stream. Coelho poses a question to the reader: which firefighter washes his face? The answer given is the firefighter whose face was clean. Why? Because he looked at the other firefighter and thought he was dirty.

This is an allegory that is reflective of my practice over more than two decades; in particular, the message that people see themselves as they experience others to see them. This is the so-called Looking-Glass Self, coined by Charles Horton Cooley in Human Nature and the Social Order at the turn of the 20th century (1902).

Returning to the firefighter who washes his face, I wonder if he would respond differently if he already thought of himself as dirty and ugly anyway. Would he wash his face, or would he think that it makes no difference?

Working with at-risk families, and supporting other professionals who do, has always been a particularly rewarding aspect of my practice. There is a great deal at stake as there is no doubt in my mind that the ideal solution for the children is to achieve an outcome where they can be safely cared for in their own home, keeping the family intact. These outcomes offer critical benefits to the children, in terms of their emerging beliefs about themselves, others, and their world (Attachment Representations), their emotional functioning (Arousal), and their learning about the accessibility and responsiveness of adults in a caregiving role (Accessibility, to needs provision). These three factors, which I refer to as the ‘Triple-A Model’, play an influential role in a child’s approach to life and relationships and, in turn, their growth and development.

One of the first hurdles to working effectively with at-risk families is minimisation, by the adults, of the concerns that have brought (or may bring) the family to the attention of child protection authorities. This, in turn, can result in the adults being resistant to accepting, and/or dismissive of, well-intentioned and needed support and guidance. In this article I share a little of my work with these families, and other professionals who do, about an approach which, across more than two decades of practice, is encapsulated in what I now refer to as the CARE Curriculum (previously, The CARE Therapeutic Framework).

Achieving relational connection is the primary task of the CARE Curriculum. When you achieve a good relational connection with another person, they experience themselves as having worth. As a result of the sense of worth they experience via the relational connection they have with you, they place value on the relational connection. The combination of these two factors are feelings of wellbeing for the person you are working with (which supports success in their endeavours) and an enhanced capacity for you to influence their approach to the parenting role.

Relational connection is an outcome of a process that begins with accepting and adopting the mindset that nobody does anything for no reason. If we accept that nobody does anything for no reason, we must consider that minimisation of the concerns that have or may bring the family to the attention of child protection authorities, and resistance to support and guidance, occurs for a reason.

In my work, shame is a major consideration for understanding minimisation and resistance. When working with the adults in at-risk families there are a number of sources of shame, often occurring together. These include (but are not limited to):

- Shame that this has happened to their family;

- Shame about being seen as having failed in the parenting role (judged);

- Shame about factors that impact family functioning and capacity to fulfil the parenting role;

- Shame that they are not the parent they would like to be;

- Shame about having let their children (and their own families) down.

The effect of their shame is that they can fail to acknowledge the full extent of the challenges faced by them in providing the safe and nurturing care their children need and may resist well-intentioned and necessary guidance regarding their approach to the parenting role.

When working with at-risk families there is always the requirement to identify areas of concern and provide guidance regarding required changes that benefit all members of the family; particularly the children. Timing is the key. If we attempt to do this too early the parents can feel even more inadequate, and more ashamed. The result is that they become ‘defensive’ in relation to the concerns that have or may bring them to the attention of child protection authorities and continue to (and steadfastly) adhere to caregiving practices that are inadequate for the needs of their children.

In order to achieve an outcome where the adults in at-risk families are more accepting of the seriousness of concerns that exist and the benefit to their children (and themselves) of receiving practical feedback and guidance that builds their capacity to fulfil the parenting role, we need to build them up. We need to help them to feel better within and about themselves and about the parenting role they are performing. We need to regulate shame.

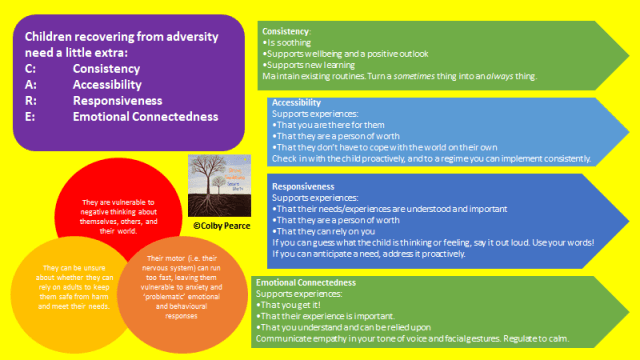

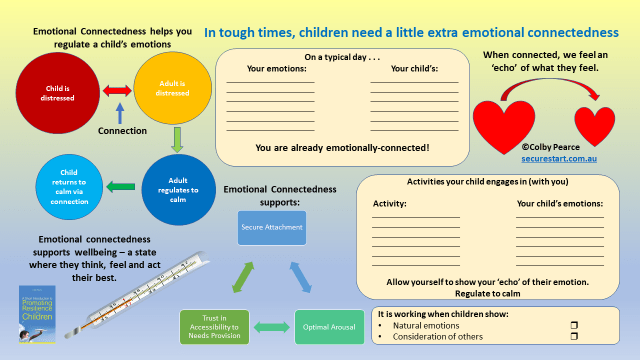

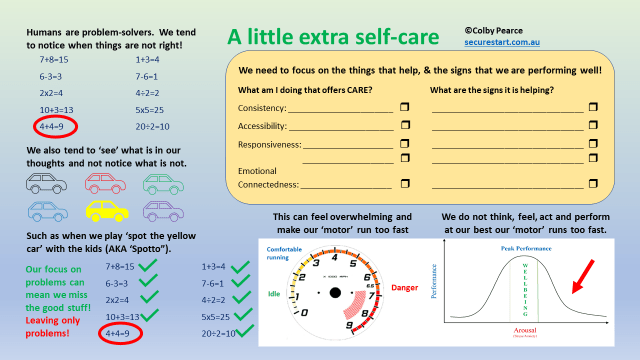

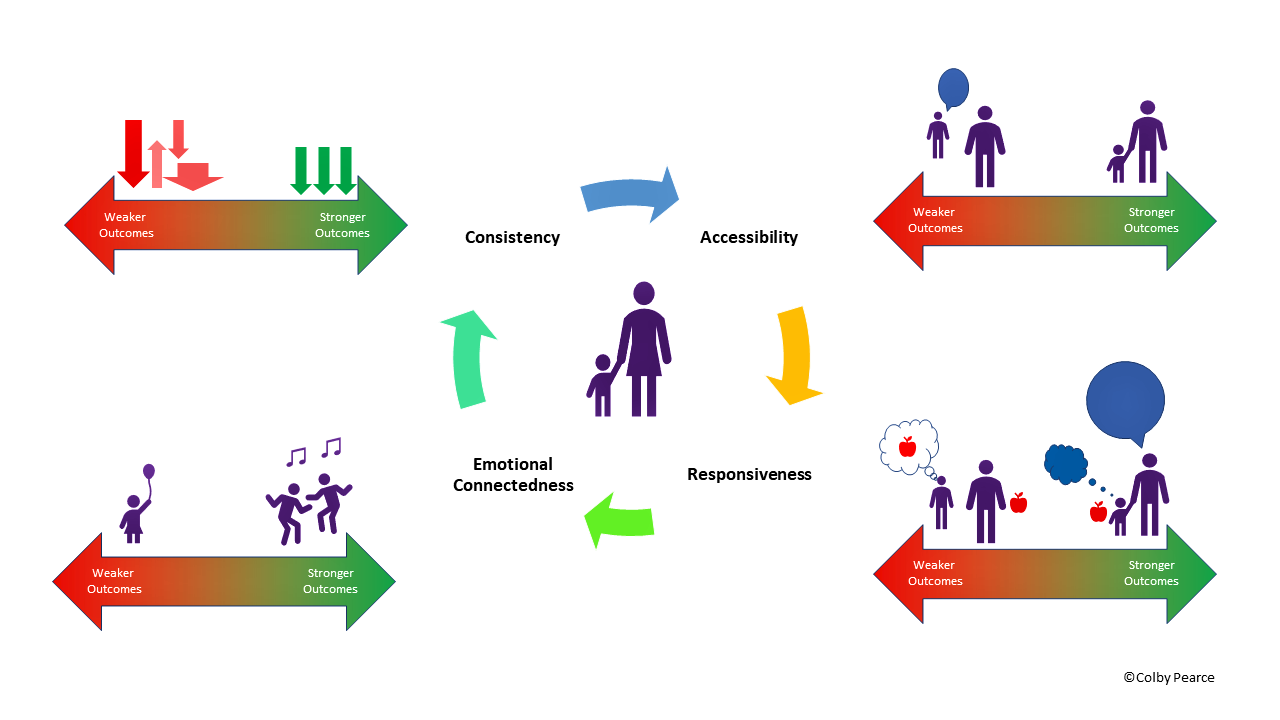

One way of doing this is to turn our minds to what they are doing well in the parenting role; that is, their strengths. The CARE Curriculum identifies four key aspects of parenting, supported by psychological science, that promote optimal development for children and young people and recovery from a tough start to life:

- Consistency

- Accessibility

- Responsiveness

- Emotional Connectedness

It is important to identify and acknowledge positive signs of these aspects of parenting in at-risk families, even if it is very small.

It is also important to acknowledge and validate their experience of the parenting role and the challenges they face. If the adults in at-risk families feel heard they are more likely to hear what you want to say:

- First, in relation to their strengths – the things they are doing well; and then

- The seriousness of the areas of concern, their impact on the children, and how best to ensure that the children can remain home with their family.

If the adults in at-risk families feel acknowledged and heard, they are more likely to accept a relational connection that regulates their shame and provides a platform for supporting and guiding them to achieve outcomes:

- of the family remaining intact; and

- the children experiencing care that is safe and satisfying of their needs.

Key Questions:

- What aspects of the parenting role are implemented consistently?

- When does the parent attend to their child?

- How does the parent acknowledge their child’s experience?

- What does the parent do to cater to their child’s needs?

- What activities or tasks do the parent and child enjoy doing together?

A straightforward guide to keeping things on track in the home during tough times. Includes printable worksheets – see preview below. 18pp

Pay/donate what you want:

Or, download here.

Preview:

For more information about the CARE curriculum and its implementation in at-risk families, do get in touch.