On a sunny autumn day David, who was four years of age, travelled with his parents to a local park for a picnic. Upon their arrival, David and his parents observed a scene replete with the recreational delights of lush grass, shady trees, warm open spaces and . . . . . an adventure playground. What happened next provides an insight into how David is likely to cope with adversity, and recover from it, throughout his life. In short, what happened next provides an insight into David’s resilience.

Adversity is a feature of the life of every child. It is present when a child is learning a new skill, on their first day of school, when they are negotiating conflicts and when their ambition exceeds their ability. Some children demonstrate persistence in the face of adverse conditions, whereas others shy away from adversity. Those who persist in their endeavours learn that adversity can be tolerated. Those who tolerate adversity and those who succeed in their endeavours under adverse conditions experience mastery. Mastery experiences are critical in the development of a perception of personal competence and capacity to influence personal outcomes. Mastery experiences under adverse conditions prove the famous words of the nineteenth century philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche: “that which does not kill me makes me stronger”.

Psychological strength, or resilience, is that quality of the child that enables them to persist in the face of adversity and recover from frustration and failure. Resilience strengthens a child and enables them to try new experiences and accept challenges. Resilience sustains a child through hardship and supports the realisation of dreams and aspirations. Resilience is critical to a child’s development and to them leading a productive, successful and satisfying life.

The promotion of resilience is a universal concern of adults with a caring concern for children. However, just as universal is the concern for shielding children from physical and emotional distress that can arise in conditions of adversity. These seemingly competing concerns can be a source of confusion and heartache for those who have the best interests of children at heart and have the potential to cloud their vision of what is in a child’s best interests. In this article I will explain how loving, nurturing and protecting children actually enhances their resilience.

My experience in working with children who have experienced overwhelming adversity in their life, together with my reading of what researchers and other professionals have to say on the matter, has led me to the conclusion that there are three key variables that impact directly on a child’s resilience; arousal, attachment and needs provision.

Arousal

In simple terms, arousal refers to the level of activity of the body’s nervous systems. Arousal goes up and down during the day, depending on a person’s mood, what they are doing and what is happening in their environment. Arousal generally is lowest when we are asleep and highest when we are in a state of high emotion. Arousal is regulated by the brain. In ordinary circumstances, arousal is thought to go up and down within a regular range, which varies from person to person. Each person’s range of arousal is affected by genetic factors, early exposure to stress, ongoing maintaining factors, and the interaction of these.

Arousal is directly implicated in a child’s capacity to learn and in their performance of daily tasks. When arousal is too low or too high, human beings are physiologically incapable of performing at their best. Mastery experiences are less likely and the child is vulnerable to repeated failure in their efforts to complete daily tasks. The result is that their self-confidence is undermined and their ability to cope with adversity is reduced. In contrast, if we can maintain a child’s arousal within an optimal range they are more likely to perform at their best, to have mastery experiences and to feel capable and competent when faced with adversity. So, in order to promote resilience in children we need to understand the relationship between arousal and performance, and to implement strategies to maintain optimal levels of arousal.

Caregiving that supports optimal levels of arousal strikes a balance between encouraging acceptance of risks and protection from potential harm, such as occurs when a parents stands at the base of the ladder while their child negotiates a slippery slide, or holds their child’s hand while they cross a busy road. Caregivers who support and encourage their children to accept risks and challenges, while protecting them from the debilitating and disempowering effects of prolonged emotional distress and repeated or overwhelming failure, ensure experiences of mastery that are essential to resilience.

Attachment

In order to feel empowered to accept challenges, children need to be able to trust that the world is generally a safe place and that others, particularly adults in a caregiving role, can be trusted and depended upon to assist them when they need it. The expectation that others will be ready and prepared to assist them is profoundly influenced by the quality of the relationships children develop with their caregivers during infancy and early childhood. Referred to as attachment, these relationships also play a significant role in the development of children’s beliefs about their personal competency and worth, and therefore, play a key role in the development of resilience.

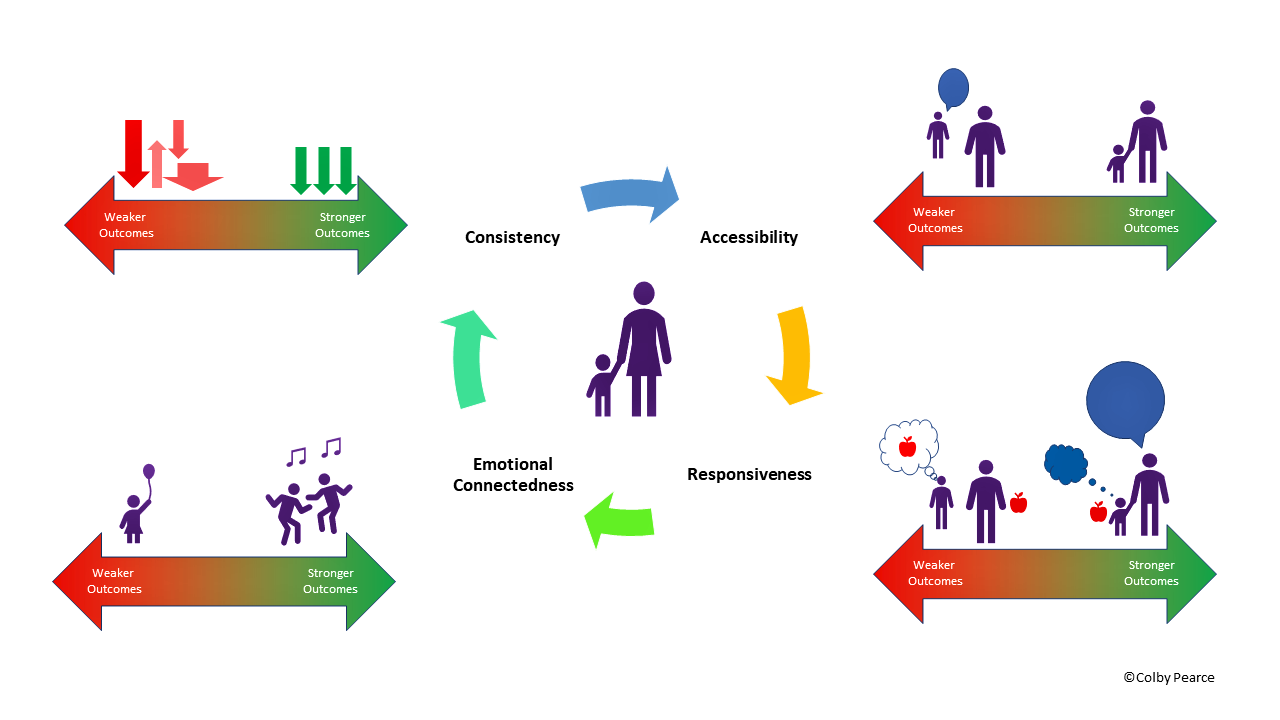

The quality of attachment relationships is influenced by three key aspects of caregiving experienced by the infant: accessibility, sensitive responsiveness and affective attunement. Accessibility refers the extent to which a caregiver is available to the infant in order to provide a caregiving response. Sensitive responsiveness refers to the extent to which the caregiver accurately reads the infants signals regarding needs that require a caregiving response, and responds to those needs. In responding to the infant in a sensitive way, the caregiver ensures that the infant experiences their needs as being understood and important. Affective attunement refers to times when the caregiver expresses the same or very similar emotion to that of the infant, such that the infant experiences an emotional union with the caregiver. Affective attunement is often observed during play and when the infant is distressed. Attunement experiences facilitate the caregiver being able to regulate the infant’s emotions until such time as the infant is able to do this for themselves.

Providing children with consistent experiences of caregiver accessibility, understanding and attunement supports the development and maintenance of positive expectations about self, others and the world in which they live. In turn, these expectations enhance children’s capacity to accept challenges and bounce back from failure. In short, it enhances their resilience. Children are reassured about the accessibility of their caregivers when their caregivers pay them attention and respond to their needs without the child having to go to great lengths to secure these things. That is, proactive caregiving supports positive representations of caregiver accessibility. Speaking out loud what you guess to be the child’s thoughts, feelings and intentions provides them with experiences that their inner world is understood and important. Instead of asking the school-aged child how was their day at school, observe their outward emotional expression and say something like “you look like you had a good day at school” or “you look like you can’t wait to get home”. Similarly, showing pride in a child’s achievements and expressing concern when they feel disappointed ensures that they feel a supportive emotional connection with their caregiver that guards against them feeling overwhelmed in times of trouble.

Needs Provision

In order for children to achieve their developmental potential and lead a full and satisfying life, they need to believe that they are able to satisfy needs that are essential to their survival and happiness. The love, care, acceptance and protection of an adult caregiver who is thought of as better able to cope with the world are examples of needs that, when consistently met, ensure that children survive and thrive. Shelter and physical sustenance are also important needs that must be met. In the absence of reliable satisfaction of needs that are essential to their survival and happiness, children become anxious. Their anxiety activates the parts of the brain that control instinctive survival responses and de-activates those parts of the brain that are responsible for logical thinking, planning, and effective action. They become demanding and difficult to reason with. They are typically resistant to having their attention diverted elsewhere. Continued denial of their attempts to secure a response to their needs often results in an escalation of their anxiety. Gaining satisfaction of their needs becomes the most important objective in the child’s life in that moment – an apparent matter of survival, with the result that they display a restricted range of interest and behaviour until such time that their needs are consistently met.

This restricted range of interest and behaviour limits the child’s capacity to lead life to the full and perform daily tasks. This is most obvious among maltreated children who, having been denied consistent access to sensitive and loving care, exhibit a limited range of interests and a propensity to engage in controlling and coercive patterns of relating to others, particularly adults in a caregiving role, in order to reassure themselves that they have access to their needs.

Consistently demonstrating understanding and responding to our children’s real needs, including their need for our love, attention, acceptance and protection, is reassuring to our children. Once reassured that they can rely on us to consistently respond to their needs, our children can get on with exploring all that their world offers without experiencing the debilitating and restricting effects of anxiety. By reducing anxiety and facilitating opportunities for exploration and mastery, reliable and consistent needs provision is a potent resiliency factor.

Finally, children’s perceptions of themselves are very much influenced by their experience of how others, particularly their main caregivers, perceive them. When their caregivers predominantly perceive them to be safe and capable, children generally see themselves the same way. Similarly, when their caregivers predominantly view them as vulnerable and incapable, children will see themselves that way too. So, have positive expectations of your children. It will support their resiliency.

So what about David and his trip to the park with the adventure playground? Well, he had a wonderful time. He confidently swung on the swings, slid on the slippery-slides, toured the tunnels, and flew on the flying fox. Under the watchful gaze of his parents he tried everything and excitedly reported his feats of bravery and accomplishment to them. His parents accompanied him to each item of equipment and warmly acknowledged his efforts. They even tried some of the more difficult items to demonstrate what was possible and remained close by to catch their child if he should fall. Upon leaving the playground he sought acknowledgement from his parents that he could come again another day.

Five ways to have a more resilient child:

- Take a balanced approach to exposing your child to challenging situations, encouraging acceptance of risks while protecting them from potential harm.

- Be accessible to your child. Anticipate their needs and reasonable wishes and respond to them as often as you are able to consistently manage before your child actively seeks to have their need or wish met. Be a proactive parent!

- Ensure that your child experiences their inner world as being understood and important. Observe your child’s nonverbal cues and the situation you are in and say out loud what you believe they are thinking and feeling.

- Show delight in your child’s achievements and concern at their distress. In doing so you will maintain a supportive emotional connection with your child that guards against them feeling overwhelmed in times of adversity.

- Believe in your child’s competency so that they will do so too.