Twenty-seven years continuous work in child protection and child welfare, including ongoing work with young adults who have transitioned from Care, has taught me some extremely valuable lessons about long-term outcomes of a childhood spent in State Care. In particular, it has taught me the importance of five factors that do not always get the attention that is needed when care and protection systems are stretched. In this brief article I will present the five key factors that I think are particularly important for best short- and long-term outcomes for children in State Care, and encourage reflection about what needs to happen when one or more of these five factors are absent. In a nutshell, the content of this article can be summarised in the graphic below:

Best connection with birth parents/family and culture

This first factor is particularly important for a young persons identify, self-worth, and belongingness. Where it is safe to do so, children and young people in State Care benefit from endeavours to promote best connection with their birth parents and/or family, and in the case of indigenous children and young people in particular, their culture (/country and community). Good quality family contact with birth parents and kin supports attachment repair, which is so important to an individual’s overall attachment style and approach to life and relationships. For indigenous children and young people, connection to culture, community, and country counters the negative impacts of systemic racism and supports the worth of their cultural identity.

Stable, Therapeutic Care

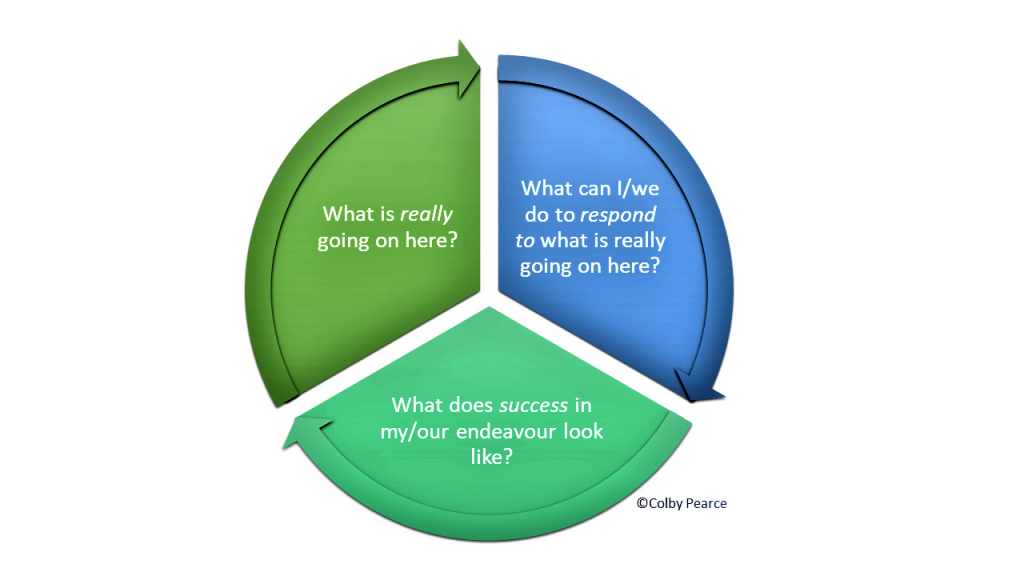

It should be a given, but children and young people in State Care do not always receive “Therapeutic Care”. In many jurisdictions, a distinction is made between ‘general’ care and ‘specialist’ or ‘therapeutic’ care. In consideration of the known impacts of maltreatment, separation, and loss, all children and young people in State Care should receive therapeutic care; where therapeutic care incorporates a shared understanding of the impacts of maltreatment, separation, and loss on the developing person, and caregiving measures that mitigate these impacts. I have written extensively in this blog, in periodical articles, and my books about what constitutes trauma-informed, therapeutic care, but it is best encapsulated by the following statement and graphic:

Trauma-informed care is less about developing strategies to address behaviours of concern, and more about responding to the reasons for them.

Trauma informed school

Children and young people in State Care experience further harm when there is misalignment in their care and management between home and school. The harm arises due to the uncertainty this causes for the child or young person about how they will be treated. A common example is the reaction of children and young people in State Care to substitute teachers (aka ‘relief’ teachers). Having experienced maltreatment, separation, and loss, these children and young people crave order. Where there is inconsistency, coercive controlling and testing behaviours represent the child or young person’s endeavours to create order and a sense of predictability, and resolve uncertainty about how they will be treated. Unfortunately for the child or young person, their coercively controlling and testing behaviours are rarely seen for what they are, and negative attributions about self, other, and world are strengthened (thereby necessitating further coercively controlling behaviour to feel safe) when adults respond to the behaviour, as opposed to the reason for the behaviour.

Children and young people in State Care benefit from consistent, trauma-informed care across the domains of their life. This is as true of school as it is the placement, as children and young people (ideally) spend much time at school, and educational participation and attainment is a known predictor of adult outcomes for care-experienced adults.

Community activities and engagement that supports many positive relationships

Attachment theory allows that children and young people form multiple attachment relationships during their formative years. Attachment theory also allows that children and young people form different attachment relationships towards different people, depending on their experience of care from the person. Attachment relationships are formed towards adults who have continuity and consistency in the child’s life, and provide care to them. The child or young person’s overall attachment style is contributed to by all of the significant relationships they form during their formative years. Where some attachment relationships are left unrepaired, the influence of these is buffered by positive attachment experiences; the more, the better.

Trauma-informed therapy

The final factor is access to an experienced therapist who practices in a trauma-informed manner. Ideally, the therapist delivers therapy that supports a secure attachment style, arousal modulation, and functional learning about access to needs provision. The therapist is also a resource for the care team of adults that support the child or young person, including at home and school, in the pursuit of alignment in care experiences across the domains of the child or young person’s life. I have written much about trauma-informed therapy, including in A Short Introduction to Attachment and Attachment Disorder.

Outcomes

In my experience, when all of these factors are in place, children and young people in State Care have the best chance of achieving positive outcomes, including:

- •Education attainment

- •Aspirations

- •Relational connections

- •Self-worth

- •Wellbeing

- •Community Participation

- •Identity & Belongingness.

Key Reflections

Where one or more of these factors are not in place, how do you think this will impact outcomes for the child or young person in State Care?

What needs to occur to compensate for the absence of this/these factors?

References

Pearce, C.M. (2016) A Short Introduction to Attachment and Attachment Disorder (Second Edition). London, Jessica Kingsley Publishers

Pearce, C.M (2012). Repairing Attachments. BACP Children and Young People, December, 28-32

Pearce, C.M. (2010). An Integration of Theory, Science and Reflective Clinical Practice in the Care and Management of Attachment-Disordered Children – A Triple A Approach. Educational and Child Psychology (Special Issue on Attachment), 27 (3): 73-86