A couple of weeks ago I had the privilege of interviewing Dr Kiran Modi, founder of Udayan Care. Across the past 30 years Kiran has been at the forefront of implementing some amazing initiatives with respect to the care and wellbeing of children and young people in India who could not (safely) be cared for at home. One of the highlights for me was the work Udayan Care does in aftercare support, from its scholarship and educational programs, to the foundation of local and international care leaver networks. I hope you enjoy our conversation.

You can listen here.

You can watch here:

Visit the Udayan Care Website here.

Transcript:

Welcome to the Secure Start podcast.

One right person really brings about a change. I said, how would you understand a child’s trauma or the need if there are hundreds of them are together? If there are smaller numbers, then you can do individual care for each and every child.

So this is the kind of stability we are able to bring in. Children know that the others may come and go, but my mentors would remain. And we’d be able to facilitate care leavers’ networks as a global care practice.

Aftercare support does not stop even when they become, and they leave aftercare. They become OdeonCare alumni. Welcome to the Secure Start podcast.

I’m Colby Pearce, and joining me today for this episode is a highly respected figure in child and family welfare in India and beyond. Before I introduce my guests, I’d just like to acknowledge the traditional custodians of the land that I’m meeting on, the Kaurna people of the Adelaide Plains, and acknowledge the continuing connection the living Kaurna people feel to land, waters, culture, and community. I’d also like to pay my respects to their elders, past, present, and emerging.

My guest today is Dr Kiran Modi. Kiran has a PhD in American literature from the Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi. In 1994, Kiran founded OdeonCare, a non-profit organization.

Since then, OdeonCare has delivered programs at national and international level with a focus on family strengthening and care reform. Under Kiran’s leadership, OdeonCare now operates in 36 cities across 15 states in India and has international chapters in the United States of America and Germany. Kiran developed the Life Living in Family Environment model for group homes, initiated aftercare programs, and launched the Odeon Charlene Fellowship, which has supported over 16,000 girls in higher education.

Kiran also established 24 IT and vocational training centers training over 30,000 youth. Kiran has pioneered several initiatives, including BICON, the Biennial International Conference on Alternative Care for Children in Asia, BICON, Asia’s largest platform for care reform, and an international journal, Institutionalized Children’s Explorations and Beyond. Kiran led India’s first care leaver study, resulting in new programs and the formation of the country’s first care leavers network, as well as a global network of care leavers.

Kiran is a recipient of many prestigious awards, including the National Award for Children for Child Welfare, India’s highest commendation for a non-profit child welfare organization, and has contributed to several research papers in national and international journals. Welcome, Kiran. It’s such an opportunity.

Thank you, Pearce, for giving me this opportunity. I don’t know whether I should call you Colby or Colby. Yeah, Colby’s good.

Colby’s fine. And I just like, we just also should acknowledge Lina, who is also joining us on this podcast, and she will be helping you with some slides that you wish to show during the podcast. And Lina is your Director of Advocacy Research and Training there at Udayan Care.

Thank you. Thank you. Yeah, so I feel very privileged to have you on, Kiran, and it’s also nice to have someone on who’s in a relatively similar time zone for me.

So, it’s mid-afternoon for me and mid-morning, I think, for you. Mid to late morning. Yes.

Yes. And I’ll just tell you that somewhat embarrassingly, when we were first communicating and you were putting IMT, I was reading that as International Median Time. I thought it meant Greenwich Meridian Time, not Indian.

So, that was my bad. We say that was my bad here. So, anyway, glad that we got it sorted out after a while.

So, Kiran, can I first ask you to perhaps just tell us about Udayan Care? And in particular, perhaps mention what the word Udayan means and how does the definition of Udayan relate to the work? It’s a lovely question, very near to my heart. Udayan is a Sanskrit word. It means eternal sunrise or a new beginning.

At Udayan Care, this is the essence that guides everything that we do. We strive to bring light into the lives of children, youth, and women who have experienced deep vulnerabilities. We were founded in 1994 and we had three major verticals.

And I would just like to tell you, family strengthening, actually, it anchors all our programs. In all these verticals, we are looking at how do you strengthen the families so that children do not remain vulnerable, they don’t get separated from the families. So, first silo, as you can see, Child Protection and Alternative Care, under which we have many programs, what you mentioned also, the group home model, which is called Ghar.

Ghar means, you know, children’s homes. Then there is aftercare. There are several programs for care leavers.

In the second vertical, which is education, skilling, and employability. You’ve already introduced this to the audience, but I would just like to reiterate Shalini Fellowship Program and the Information Technology and Vocational Training Program. They are looking at vulnerable girls from the communities, youth, and empowering them as per their capability.

Higher education, vocational training, and finally getting into employment. The third silo, which is very, very near to my heart, because I’m also realizing again and again, just service delivery will not make systemic change. How do you bring about that systemic change? That’s why we started this vertical, and I’m so glad that Lina is here with me.

She’s heading this department. Art means advocacy, research, and training. So, we’ve been doing a lot of consultations and seminars.

You’ve already mentioned biennial conferences, and I’m so happy to say that in October of this year, 2025, we will be having an international conference. This will be the sixth one in Malaysia. We take out an academic journal you’ve already mentioned, and I always like to say that it’s a niche journal, you know, because it’s not about social work.

It’s not about child rights. It’s actually about children who are without parental care. How do you strengthen the communities so that every child gets a family-like environment to grow up in? Then, we’ve been conducting a lot of research studies.

Almost 100 research papers have been published in different journals, including our own, and trainings, which is again very, very important because we are working with several governments in India where we are training the child protection functionaries into delivering their work even better and learning from them as well. So, it’s not only via training. We are also learning, and I would just like to say that, you know, children without parental care, when they get all these opportunities, you know, the underserved children and youth, they can really go places.

That’s lovely. Yeah, it’s such an awesome endeavour or endeavours, array of endeavours that you’re doing for vulnerable children and young people, and I’m very pleased to be able to hear about it today. You said something in there that is interesting to me, and I think it’s important to acknowledge that just when you said just providing a good service or service provision alone doesn’t necessarily bring about systemic change.

We do need to be doing research and advocacy around the work that we do, and I was introduced to an interesting term by a recent guest, which was pracademic, by which she meant, yeah, being both a practitioner and a researcher and doing, and connecting that, and her name is Lisa Ethison. She talked about shame containment theory, but it was new to me, and I think she was making the point that not only is it necessary, as you say, to do something more than just provide, do service provision. We are the best people to do research in this sector, the service providers, yes.

The practitioner’s experience has to inform policy and research. Yes, yeah. So, what led you into this work? I noticed you have a PhD in American literature, but you’ve kind of gone down the child and family welfare path.

What led you into this work, Kiran? So, actually, you know, the life experiences. As a child, I was only eight years old, and I just can’t forget, I was on a very, very busy road, full of people with my parents, and suddenly, I found myself lost. And I cried my heart out.

And finally, the police took me to the police station where my parents came after some time looking for me everywhere. They were looking so worried. And I was so relieved to find them.

This thought remained with me, just a few seconds of parental separation, you know, it formed my childhood, it informed my childhood, it continued with me in my youth, you know, so I think it was a very powerful experience, which really, you know, made me understand what do children without parental care go through. And then a quirk of a fate, I had personal tragedy. And from the world of literature, suddenly, I was thrown into the world of reality.

And I realized I need to do something. And especially when I found that my son was doing so much with his meager income in America, I really need to take that work forward. And I started thinking of setting up an organization which can serve the underserved.

Here, in the initial one year, it really took me, you know, I went around to all kinds of causes, at least 150 organizations I visited. In one of my visits to an orphanage, there was a child who just took took hold of me and said, please take me home. Oh, that remained with me.

That remained with me and my childhood trauma of that parental separation came back to me. And I said, here is and that’s where in India, the model of children’s homes were always, you know, even the juvenile justice act was talking about 100 children’s homes. So largely, children were very big homes, and they were little away from society.

Based on all that, and my personal belief in that the family model has to be there. We set up our life for them because means living in family environment. That was my first venture into the development sector.

Yeah, lovely. And I think I think such a stark portrayal of the an experience for you of what it feels like to be separated from family and that extends even to children and young people whose families are struggling with their care. Yeah.

And or are very dysfunctional. The children still feel keenly that separation. Yeah.

So you you went to you visited more than 100 organisations. I think you said more than 150 organisations in that year before you went down down this particular path. And you started out in 1994.

And how easy or difficult was it to to establish Udayan care and the work that it did? Um, I would say it wasn’t really difficult in the beginning. You know, all you need is some kindred soul who speak to you, who understand where you come from, and just find those kind of people who will support you. So once you’ve built that kind of a support system, and the legal legalities of setting up an organisation is done, and also your cause is very clear, then you know, it’s not such a big challenge.

But of course, limited infrastructure, low awareness in India about child rights, and especially low awareness about small homes where children could live like a family. So there was a lot of scepticism. And the government was running such large homes to get a license for a 12 children home was also quite difficult.

You know, so I really had to fight it out. But you know, as they say, one right person really brings about a change. There was this officer in one of the women and child development department, she understood where I was coming from.

I said, How would you understand a child’s trauma or the need if there are hundreds of them are together? If there are smaller numbers, then you can do individual care for each and every child and the adequate resources could be provided. So she understood my point and they allowed me the first license. Then of course, more licenses came and we set up 17 homes at one point of time.

Resource mobilisation, as you know, it’s always a constant challenge for any organisation. But I think we were really blessed. We have been able to find, actually, you know, I always say the man upstairs, God, he’s there to help us.

So I don’t have to worry about resource mobilisation. He takes care. The biggest challenge was how do you find the workforce who is qualified, who is trauma informed, and who are interested in learning and sticking on with you.

Children, they have suffered unstable families, you know, broken relationships, and then they come here in a children’s home. They want, you know, that kind of stability. But the reality of the world, at least in India, is that it’s very difficult to retain people because, you know, it’s becoming like how any profession, you know, earlier, it used to be different.

It wasn’t really social work was really looked at only as a profession. Mostly people with large hearts, they were coming here. So but the things have started changing.

So it becomes very difficult to get qualified and trauma informed workforce. Also to develop partnerships, both at the local and international level, with policymakers to your next door neighbour, you know, how do you develop these kinds of partnerships with different NGOs with different funding agencies. So these collaborations were again, difficult, but it wasn’t very difficult, we were able to do.

I think the key is you have to persist, there has to be a transparency in your work. And of course, an unwavering belief in your mission, which can take you forward. Yeah, yeah, lovely.

Something that you said in there that resonated with me quite a lot was, I strongly believe that when we just focus on doing a good job, that the, you know, the other things that are necessary, the people, the financial arrangements, they tend to fall into place. And at least that’s what I found. And it sounds like that’s what you found as well.

Absolutely. Yeah. And also another challenge, which I would like to put it across, is the ecosystem which is changing, you know, the legal legalities, the legal provisions, whether it is for foreign donation, whether it is for, you know, different kinds of paperwork, it’s becoming, you know, so much of paperwork in India also, which I realised when I visited some organisations abroad, that the social workers end up doing a lot of paperwork.

And we never used to have so much, but now it is increasingly, you know, becoming more and more. So it becomes like a tick box for many things. So which is a little bit painful, but we are trying to deal with it.

Yeah. Yeah. I don’t think you’re on your own there.

I think that there, as you say, you saw that in many of the organisations that you visited, and even here in Australia, in the jurisdictions I’m familiar with, I think the paperwork has long been a bone of contention amongst workers who really just want to help children and families. Yeah. Yeah.

You know, Kieran, one of the things that really intrigued me about your organisation and your bio when I read it was the care leaver study that you did. Care leavers are very near and dear to my heart. I have primarily worked long term as a psychotherapist in the child protection space and at home care space.

And I’ve kept in touch with, or at least they’ve kept in touch with me, a great many of the care leavers that I knew when they were younger people and in care. And I’ve always been really concerned, I guess, about the lack of support for a great many of our care leavers and the struggles that they have post care. So I’m really interested to hear a bit more about your care leaver study and how that was then translated into better support for care leavers.

Yes. Since, you know, as we’ve been talking about, both of us agree that, you know, practice should inform your research and, you know, your advocacy. So after running these homes for so many years and their children were growing up 18 and then they were given aftercare, so they were supported fully.

And we realised that many organisations are not able to do that kind of work, even though the government mandate was there to support youth, you know, as they are growing up at 18. You can’t expect them to be on their own at the age of 18. But it wasn’t happening in a very big manner.

So we decided to conduct a study and we were lucky enough to get partnerships from UNICEF and Tata Trust. So this study was conducted in five states of India, where we took up 500 youth. And first of all, it was so difficult to trace children who have gone out of these institutions if they are not being supported.

So it was very, very difficult to find them. But when we developed our questionnaire, which was, again, you know, a very big process of, you know, to and fro, getting participation from the care leavers also. Finally, we finalised our tools, and then we started doing studies.

And some of the gaps which came out, I would like to just tell you, and the youth that they were telling us, we realised, where are the gaps? Gaps are in identity and legal awareness. So they don’t understand who am I, as a care leaver, am I a care leaver, or am I a human being, you know, who should be supported? What is my legal awareness level? Most of the care leavers did not even know that they are entitled to aftercare support. Housing, most of them did not know after 18 where to go, because in India, we don’t have any special system, other than some aftercare hostels set up by government or NGOs like us.

So there was a big problem about housing, if they would like to take up an apartment, it wasn’t easy for them to get the paperwork done. Independent living skills, what we realised, children who were growing up here, in institutions or in foster care, everything was done for them. So they were not learning the independent living skills.

So we felt that this is a big gap. Then another gap that came out was social support and interpersonal skills. When you are in a children’s home, largely, you are meeting children of your own kind, when you go to school, it’s only for a short while, then again, you come back to the routine of the home, you don’t get an opportunity to go out and meet society at large.

So they become, you know, their interpersonal skills, they are not able to develop. We also realised children who suffered so much trauma and abuse, when they were separated from the family, sometimes family itself was the perpetrator. And so many times, after, you know, leaving the family, they land up on streets, there again, more, you know, trauma is perpetrated on them.

How do they have emotional well-being? Are the care homes able to address their emotional well-being, give them support, trauma-informed care, so that they are able to? I mean, nobody can really overcome trauma, this is what I believe, at best a scab is formed. And at the littlest of the provocation, the scab is gone and the blood starts oozing. But still to even to form that scab and even to inform the children how you can deal with your issues, the coping mechanisms, the resilience, how much is being done, we found there was a big gap.

Physical health wasn’t so bad, 78% children, but they did not have any insurance. So without insurance, it’s so difficult to go for any kind of a proper care. Education and vocational skills was taking a real, you know, back step, because the children, their education gets disrupted when they leave the family.

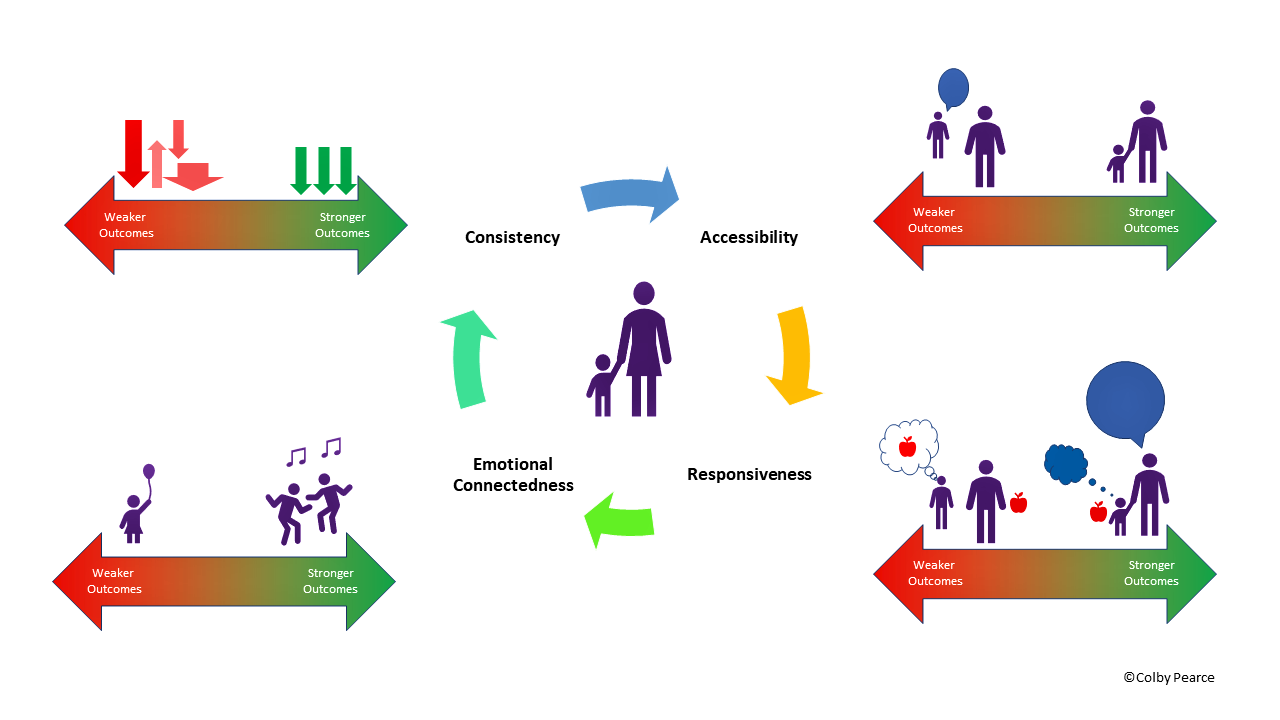

And sometimes from institution to institution, from one foster family to another, the education system is such that, you know, dropout rates increase, and it becomes very difficult for them to cope up. And if you don’t have the required education or vocational training, it’s absolutely impossible to gain financial independence and to develop a career. So these are some of the things that we do, we develop, and we call it a sphere of aftercare.

So we feel every young person coming out of a childcare home or from a foster care, they should be getting support on these eight domains. Because these are, as you can see, these are interconnected, nothing is standing on its own, you give housing, you don’t give others, it doesn’t make sense. So it all has to come in a package so that the youth, they are able to sustain themselves and go to the next level in their lives.

So you also asked me, how did it support the larger system? So these recommendations which came out where we, three things I would just like to point out, although there are many things, but we also have lack of time. So we were talking in India, for every child in an institution, there has to be an ICP, individual care plan. But at 18, it has no connection with your care plan, which was made for you.

It has no future because there is no aftercare plan made. So we very strongly recommended that there should be an aftercare plan for every youth who is coming out of after 18. So it happened in 2023, Mission Vatsilya, which is a government run scheme, there they are introducing IAP, which was a very big satisfaction for us.

In our recommendation, we said there has to be an increased investment on aftercare. They were giving only 2000 rupees per youth and 2000 rupees is so measly, so measly and nobody can survive on that. So we requested you make it more.

So from 19 pounds now to 38 pounds per month, which is still quite measly, but still, because there are homes which are being provided, so they’re able to maintain. We also said there has to be a lot of linkages and convergence between educational institutions, between skilling ministries, between all these ministries must come together. And more such, with this convergence, different government departments should be addressing the issues of the aftercare youth.

And again, the Mission Vatsilya talks about it. We also said, how do you strengthen the voices of caregivers? Before that, there was no caregivers, sorry, network. So we, I mean, I always take very, I feel very happy that we were the instrument by which many caregivers came together, and they set up platforms for peer networking and mentoring and supporting each other.

We also talked about that there should be proper aftercare guidelines. Of course, in the law it is mentioned, but without a proper guideline, how do anybody function? So I’m so glad that now state level guidelines are there in many states, as many as 13 states, and others are also developing their own guidelines. So actually, aftercare and care leavers is becoming a word which people have started understanding and recognizing.

We also did at our level, many models we developed to support caregivers. So this evidence that we created helped us in incubating programs, because again, as I’ve been saying, practice, you know, informs research, and research should inform practice, because if you don’t bring back those learnings, there is no point. So we started our aftercare outreach program in 2020.

And here, in six states of India, we are taking care leavers and supporting them for their next level on those eight domains that I showed you in the sphere of aftercare. Then we have started care leavers networks, which I’ve already told you. And now the care leavers are themselves, putting it forward in many states, care leavers themselves have set up such, you know, networks, many states, NGOs are also coming forward, even UNICEF has been a very big driver to bring care leavers networks.

And we started a fellowship, which is a very, very beautiful fellowship. It is called LIFT, learning and fellowship together. Here the youth, they have to submit a proposal by which they are going to support other care experienced youth.

So every project is different. Somebody is taking up developing life skill programs, somebody is developing a research program, somebody is developing podcasts of care leavers, so that their voices can be heard. So beautiful, you know, projects they come up with.

We are also giving a lot of support to state governments, especially on FBAC, family based alternative care programming, which includes aftercare. So these are some of the states, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Telangana and Jharkhand. We’ve been generating a lot of evidence through publications, researching and publishing it.

As I told you earlier about our 2018-19 study beyond, you know, the one which I talked about. But after that, there have been a lot of researches which we have been publishing in different journals. So in a way, care leavers, you know, we started very, very locally, but we were very lucky that we had other partners joining in, international partners, and we’ve been able to facilitate care leavers networks as a global care practice.

So some of Australian care leavers are also part of it. We also realized that, you know, families need to be supported. If the families are supported, if the children are integrated with the families, why would they leave the families? So we started, you know, programs which is called Fit Families Together.

It is working in three different localities of Delhi, and where we are working with families so that the children who have been sent back from institutions can get properly integrated. And how do you prevent further separation? So these are some of the programs which actually emanated from the research study. We have already talked about this particular journal.

And this journal is doing very well. And we also do a global monthly news wrap up. So if you see, 25 plus research studies have been conducted, 93 plus research papers and articles have been published, and global monthly news wrap up.

I’m really proud that Sage Publishers, they are our partners, they are world famous publishers, they are our partners for this journal. In advocacy, I’ve already talked about you, you also mentioned BICONS, and first care leavers convention was done, it was an international care leavers convention. After that, it was followed by the second one.

So actually, our practices can improve, there is advocacy, evidence generation and research, all feeding into one. So this slide, you know, actually represents that. Hiran, I’m just sitting here, gobsmacked, we say, or in awe, that it is remarkable, truly remarkable, what you’ve achieved.

I come from a sector where, a jurisdiction, sorry, where sector organisations and sector supports are very fragmented. And seeing what you’re doing in a day in care, you know, in terms of providing a therapeutic family environment for children and young people who are separated from their parents or can’t reside with their parents for whatever reason, through to support post care, integrated with education. We know everywhere that education is one of the absolute keys to rise out of poverty, but also for our children and young people to have normal lives.

Post care. So it’s remarkable what Udayan Care and you have achieved. And another thing that you said very early on, that I want to just mention, because I agree with it very much, where you said, children don’t get over trauma.

At best, it scabs over. And I think if I heard you right, you were saying, you know, depending on what happens after, and particularly after care, that the scab can be picked away or otherwise. And yeah, I use the term enduring sensitivities.

I think it’s, I think we’re all impacted in some way, or at least shaped by our childhood experiences. And I hear a lot about trauma recovery, trauma repaired, you know, as if we can achieve an outcome where it is as if the trauma did not occur. And the reality is that that’s a false, yeah, it’s a false quest.

We’ll never, we’ll never get there. And I think saying it is really important, because it takes the pressure off everyone. We don’t, we know what will help, what will help will be connection to, that was the other thing I didn’t mention, that I loved about your presentation, restoring connection and strengthening connection to family.

The most healing relationships, in my view, are those family relationships. Absolutely. Yep.

And so, yeah, just, I’m just, I’m just blown away. Just, it’s just remarkable to see what you are doing there, from an integrated service provision point of view. Thank you.

Thank you. I would just like to, you know, add here, in the last three years, eight of my youth who came out of our children’s homes, they all studied in UK. And on complete scholarships, they did their masters, you know, I mean, so it’s not that that trauma was erased, trauma remains, I always like to say trauma lodges in your heart.

You know, it’s not easy to and every given situation, it does come out on the floor. But the issue is, what kind of resilience skills, what kind of coping mechanisms you’ve been trained, so that you can, at least at that time, you are able to overcome that sorrow, that pain, that self pity. Yeah, so I think that’s very important.

And I think resilience training takes a lot of our, you know, focus. Hmm. The other thing that I think is of particular, particularly close to my heart, because I’ve also developed therapeutic models, but the life program, the living in a family environment model that you talked about.

And I’m just wondering if you could might tell us, share a little bit more about it’s quite a key elements. And I’m particularly interested in any challenges you had in rolling it out or delivering it and how they were overcome. So actually, you know, as I told you in the beginning, also, that large homes were the reality.

So when we started, you know, residential group homes, which are called sunshine homes, or then as I told you, sunshine, so these are sunshine homes, you know, so that they can dispel darkness from their lives. So we developed a strategy, which is called life, living in family environment. First of all, I did not like that, you know, system, where every eight hours new people are coming in the next batch of people are coming in, there is no continuity there.

So we developed a system by which the carer team, you know, the carer team, it was like permanent, voluntary mentor parents, like I’m also a mother to, you know, so many of them. So these are all volunteers who commit themselves for life. So that means, as long as I am alive, as long as this home runs, my services are for the children.

But since we have our own families, we are not able to stay with the children, but we are there for them. So we are meeting them twice or thrice a week. And whenever they need us, we are available on telephone, we actually become a window to the world for them.

So these are voluntary mentor parents, then other than that, there are supervisors, in-house caregivers, psychologists, health specialists, social workers and volunteers. And at the office level, there are managers who are managing the whole thing. So at this moment, there are 11 Udayangars, there used to be 17, we’ve reduced the numbers, I will talk about that later.

Let me first finish this particular part, what is our model? So the model is to develop a beautiful synergy between volunteers who want to give and volunteers who are committing for life. It’s not that I can come in today and tomorrow I can go and the professional workforce, then, you know, community ownership. We thought it was so important that the children should be in a community, and they should be available to the neighborhood.

So there is a community park where they are playing with others, and they are mingling with others, they are going to the neighborhood shop to buy something. So it becomes like a normal childhood. And community ownership was so important, communities, they start owning them, for them, these become their children.

They go to middle class neighborhood schools, and there is a lot of social integration. And this gives them a very good realistic worldview. So that when they grow up, suddenly they don’t have to face this monster called society, you know, because they are carrying some very bad image from their childhood.

So we want them to get adjusted, then holistic upbringing here through a participatory approach, they are provided quality education and all that those eight domains which I showed you are for their all round development. We are working on that there is a safe and non discriminatory environment. There is vocational training, education, life skills, exposure, exposure to the market, secure and stable attachments.

I will be talking about this attachment theory of John Bowlby. He was my biggest influence, you know, when I started these homes, the children who have disrupted attachments, and how do we make their insecurity and turn them into secure attachments? How do we train them into this? That’s why we brought in the voluntary mentor parents with and the social workers and everyone, all of us are very consciously working on developing stable attachments in them. As I said earlier, individual care plans are made, where each child we discuss with the child and the full team, what should be the plans for going forward.

And these are the therapeutic and then the mental health, you know, therapeutic interventions are tailored to each child’s need. So certain things we are able to address in a group system group workshop, certain things they need individual attention. And we are constantly researching on what we are doing.

We have developed our own tool, which is called QA and CC, already 10 years data we’ve been able to collect. And three research papers have been published, their children tell us what is going right for them and what is not going right for them. And just to maintain complete, you know, transparency, none of our staff conduct these, we are getting, you know, master students from social work, they come in every year, and they conduct these tests, so that you know, children are able to voice whatever they want to say.

So trauma informed care approach is very, very strong. And we do continuous training of our staff, the staff is, you know, quite fast rotating. So we try to retain the staff, we try to, you know, train the staff into trauma informed care.

And we, our ultimate aim is that the environment of the home should be trusting, the child should be able to trust us should be enabling and stimulating so that they are able to become productive citizens of tomorrow by giving aftercare support. Aftercare support does not stop, even when they become and they leave aftercare, they become Udayan Care alumni. And we continue to handle, I’m very happy to say more than 2000 children have come out of our homes.

And we’ve got at least 100 children who are married, without our support, wherever they needed our support, we were there to give them away in marriage. And we have got more than 70 grandchildren in the family. And I must say about the mentor parents, we are 29 mentor parents who are looking after these children, like our own.

And long term, you know, Dolly Anand, I mean, she really brings me so much joy. Now she’s 84. She joined me when she was 60.

Even at the age of right age of 84, she goes to the children’s home, talks to them, makes them you know, see the sense and you know, discusses things with them. So this is the kind of stability, we are able to bring in children know that others may come and go, but my mentors would remain. So that’s a very big feeling, you know, of stability and security for the children.

So this is our therapeutic model. It’s remarkable. I was just, I was kind of blown away at the voluntary mentor parents.

And what a remarkable thing to do to provide, because you’re right, in any jurisdictions, there is always mobility of professionals. But to have that stability of connection through those voluntary mentor parents, and I guess they get a, you’re one, you were saying, I guess you get so much joy out of that as well. Oh, my God, you’ve said the same words, which each and every mentor parent says, you know, because there is no monetary outcome for them.

It’s only sheer giving. So whenever you ask them, you do so much, what do you gain return? They said, what can we give them? The amount they give us back, their love, their trust, you know, just to, I mean, Lina here, she has started working so much with the aftercare youth, and all of them have started calling her mama mama. And they go and land up at her house, you know, because they know here is this mama will be available to me.

So I think this kind of a feeling is so important for children to have that secure base where they can turn to. And I think it is. Yeah, absolutely.

Absolutely. Sorry, I was I was still thinking about the the meat, you know, it just gives your life so much meaning to be giving to vulnerable young people who otherwise wouldn’t have these wouldn’t necessarily have these stable and lasting connections that are so important for their for their growth and development. I could do a whole podcast with you just talking about the voluntary mentor parents, I think, and their relationships with the children.

But sadly, we need to move on a little bit. And my last question to you, before I give you the opportunity to ask me a question, if you like, but my last question to you is, what advice would you give to an organisation that is trying to implement a model of care? So these are some of our ideas that we’ve been using. You know, how do you integrate children in institutions back into families and prevent, you know, the separation? So and unless you keep that mental health perspective on the top of your priority, you will never be able to do the justice.

It has to be a strength based framework. So what we do is trauma informed care. And my advice to everyone is, you have to bring in into your system of working and training the staff, letting the children know you have suffered trauma, there is no problem in that we can still, you know, move on.

And tenets of bold, boldness, attachment theory, how do you develop secure adult interpersonal relationships? This is why, as I told you, mentor parents, I know it’s a very difficult system. And it’s not easy to find this kind of a lifetime committed people. But I always say if we could get them, I’m sure out there hundreds and hundreds of them, you just need to be on the lookout, you need to provide opportunities, people would be coming, they would be willing to get trained, they’ve and they are experienced parents themselves.

So parenting experiences plus attachment tenets, they will be able to apply to the children. We also believe a lot on Erickson psychosocial theory of development, the eight stages. So we keep on training our staff on to these stages, unless you understand where the crisis is, and you are able to resolve it and go to the next stage.

Otherwise, you will remain there. So it’s very important for all the organizations who are working with children, at least in my mind, to have this kind of a developmental approach. And we have placed our children right in the midst of the community.

So when I found Yuri Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems approach theory, I was blown away, because this is exactly what we were doing without, you know, naming as microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, macrosystem, or chronosystem. But we were doing everything, whether it is, you know, at the community level, whether it is at the school level, whether it is at the state level, we were trying to bring children and people, community together. So I think these are very, very important.

This community approach, when we go to the community, what we found most of the community members, they feel so hopeless, because they feel I’m not able to look after my child. So take away my child. How do you convince them that you have enough strength in you, and you can look after your children.

So I think, you know, even something as simple as genogram, you know, you make them remember who are the people around you, who could be, you know, your partners in bringing up your children, what are the assets available in your community, in your area on which you can impinge upon, I think for any organization, it’s very, very important to keep these in mind. Then, as I’ve been saying, again, and again, throughout that bring building resilience, improving coping skills, emotional and social well being, make them into a social person. Don’t let them be a loner in a children’s home, or even in a community when they are not able to come out, you have to make such systems by which the child is able to cope and become a social being.

We have to address behavior modification, children who have suffered trauma, they need, you know, behavior modification. So we need to develop a proper, you know, plan for each child, how do you ensure a productive future, and everything should be done in a case management approach, and a higher purpose in life. So we haven’t mentioned in our eight domains, the spiritual aspect, but I think it’s so important to have a higher purpose in life.

And that the moment you know, anybody who has suffered, they start feeling a higher purpose in their lives, their hope and faith goes up. And that’s what we are here for. And that’s what all organizations should be aiming for.

This is my firm belief. Yeah, it reminds me a little bit of what I was saying about the house mental parents as well. When we when our life has meaning, we thrive.

And that was very much the message of Viktor Frankl, the author of Logotherapy and Survivor of Auschwitz and other concentration camps during the Second World War. So yeah, and very again, another theoretical orientation very close to my heart. That’s wonderful.

It’s wonderful to hear that, that you can instill in children and young people, in the children and young people that you serve in your country. I mean, they’re collectively ours. It is one human race, isn’t it? I must make a caveat, it’s not possible to have 100% result.

And we must not get upset or feel start feeling guilty that I’ve not been able to serve this child, because you’re trying your level best and you’re making an individual specific plan, still plans fail. So you have to take your successes and your failures in your stride. It’s the trauma is so complex.

And the kind of trauma they have faced, we can’t even imagine, you know, we have not suffered, they have suffered. So they have their own reasons. So we have to keep that in mind, and accordingly deal with them and deal with our own frustrations and sense of failure.

It’s very, very important that we take self care. Otherwise, we will never be able to do justice to the children. Yeah, I think it’s really important that you mentioned that, that it is a tough area to work in.

And that what you said links in with a couple of my previous podcasts to one with Dr. Nicola O’Sullivan talking about supervision, and the importance of reflective supervision and acknowledgement that acknowledges the impact of the work on us. The other thing that came to mind was Graham Kerridge’s podcast. That was, I think, at this by this day, the most recent past podcast that I released.

And he told the story of a young person who he worked with at the Cotswold community in the UK in the late 1970s, and who recontacted him or contacted him via LinkedIn only a few years ago, but some 40 years later for more than 40 years later. And in telling that story, Graham did mention that the young person, you know, that there were challenges and it wasn’t the best outcome that you would want to draw everyone’s attention to in terms of his early progress in life. But then he found his way.

And Graham tells, you know, what a wonderful story about his, that young person’s achievement, achievements in their adult life. And I think what that, see, a lot of people say to me, you know, they worry about whether what they’re doing is enough for these young people. And, and I’m always put in mind of the One Good Adult research, the One Good Adult literature, which says, and I’m paraphrasing here, but as long as a young person, when they’re growing up, can identify one person who is there for them, who understands them, who they can turn to for support, then that will make, yeah, they’re much more likely to have a normal life.

And I say normal life, because, again, I’m finding this in another, another recent guest, Adela Holmes, talked about aspirations for our young people should be a normal life. Just a normal life. Yeah, just a normal life.

Yeah. Yeah. Lovely.

Kieran, I always give everyone, I’m not sure how about your time, but I always give everyone a chance now to ask me a question before we go. But did you have a question you’d like to ask me? Actually, can I ask you too? Yes, why not? So you’ve been doing such beautiful podcasts, two or three of them I’ve been able to hear, and I gained so much from them. I want to understand from you, what is one surprising or transformative insight you would like to quote after meeting so many people who are practitioners in this field, you are speaking to people from around the world, one surprising and transformative insight, which you were not exposed to earlier? This is my first question.

And the second question, in the AI world, you know, how do we manage, you know, the learnings that we are making? And how do we maintain children’s confidentiality and safeguarding concerns? These two questions I have for you. Well, I’ll ask, I always pride myself on being able to answer questions without notice. The second one on AI, I’m, I have to say, I don’t know, with that one.

I think that the AI, the technology, the AI field is just developing very quickly. And if you don’t, if you don’t, if you don’t kind of stick with it, it, you know, it leaves you behind very, very quickly. And I had Kath Nibbs on, Katharine Nibbs on, I think was podcast episode four.

She’s an international expert in online harm for children. And she reflects on just how difficult it is, seemingly, or at least how, how far behind adults are in having a full appreciation of the online world and where children and young people are at online. So I’m, if you haven’t already, have a, have a listen to her podcast and, and, and perhaps follow up with her.

I’ve seen your YouTube. Aye, okay. Yes.

So sorry, unfortunately, all I can say is I don’t, I don’t really know the answer to that. What I do know is that we can’t, we probably, we need to educate our kids, we can’t, our young people about what’s out there. We can’t restrict it because children who come from deprivation, apart from it being totally unfair, they respond very badly to further attempts to restrict.

And, and also being overprotective and restrictive in that way will mean that they will feel different to their peers. In terms of what I, there’s been, there’s been quite a number of insights. The things that have really stood out for me have been the importance.

Well, I, I came into doing this very much of a mind that you need to have time, you need to take time to think about what you’re doing. If you don’t take time to think about what you’re doing, then you become, your work becomes very heartless and procedural. And with regard to the heartless point, I think one of the things that I’ve been talking about with a number of guests has been the importance of acknowledging the, the impact of the work on us.

And being aware of our, you know, our own capacity to, to perhaps not provide the best level of care because it’s, it’s uncomfortable for us because of some aspect that it brings up for us. So I think I think that addition to what I was already coming in with about thinking about care, I think thinking about the work we do, thinking about the impact of the work we do and where our blind spots are. Nicola O’Sullivan talked beautifully about this in podcast number three.

But you know, what it’s, it can sometimes feel isolating working in this space. You, it is, it’s very nuanced, it’s very specialist, and you can’t just talk to anyone about the work that you do and for them to fully understand and get where you’re coming from, what your experience is. So what the thing that the overwhelming experience that I take out of this is, I’m surprised that so many people want to speak to me first for a start.

And it’s just been, it’s just a great experience to talk to people who, you know, who are like minded and have a similar experience of the work. Great, thank you. Thank you.

There’s so much of learning here. Yeah. Well, and thank you.

Look, it’s just been wonderful to have you on board today, Kiran. Perhaps, can you just tell people, our listeners, where is the best place to get to access more information about Udayan care? Yeah, so we are headquartered in Delhi. And as you said, we are, we have expanded our links to almost every part of India.

And the website is there, http://www.udayancare.org. So people can always find us, they can find me, Kiran Moody, I’m on LinkedIn, I’m everywhere. So they can find me, I’m always available. I’ll put those links on the podcast, the audio and the video that’s on YouTube.

Look, Kiran, again, thank you very much for appearing. My plan at the moment is to listen back to each of the podcasts that I’m doing in a little while, and write down all the questions that I would have liked to have asked you today, but didn’t have time scheduled to do that. So I wonder if you would be happy for me to recontact you at some later date to ask you a few more questions.

Absolutely, more than happy. Because, you know, it makes me also reflect, and like you said, you need time to reflect on what you’re doing. I’ll be more than happy.

And especially, you know, our transitioning from the institutional care model to the family-based care. Today, we didn’t have enough time for that. I would really love to talk about that.

Thank you. Yeah, absolutely. All right.

Well, thank you, and all the best to you. And I’ll speak to you another time. Yes, thank you.

Bye.