John was formerly a UKCP registered Psychotherapist and a full member of the British Psychotherapy Foundation (BPF).

John was also the Chair of Trustees of the Gloucestershire Counselling Service and Trustee of the Planned Environment Therapy Trust and the Mulberry Bush Organisation.

Between 1985 and 1999 John was the Principal of the Cotswold Community, a pioneering therapeutic community for emotionally unintegrated boys.

Thereafter, between 1999 and 2014 John was the Managing Director of Integrated Services Programme (ISP), the first therapeutic foster care programme in the UK.

I was very much interested in John’s views from working across these different types of out of home care. I hope you will enjoy our conversation too.

Listen here.

Or watch here:

About the Secure Start Podcast:

In the same way that a secure base is the springboard for the growth of the child, knowledge of past endeavours and lessons learnt are the springboard for growth in current and future endeavours.

If we do not revisit the lessons of the past we are doomed to relearning them over and over again, with the result that we may never really achieve a greater potential.

In keeping with the idea we are encouraged to be the person we wished we knew when we were starting out, it is my vision for the podcast that it is a place where those who work in child protection and out-of-home care can access what is/was already known, spring-boarding them to even greater insights.

Transcript

Welcome to episode two of the Secure Start podcast. And I think it probably took about three or four years before the therapeutic culture was really established. Their unintegrated personalities meant they needed a very integrated environment to hold them, contain them, to manage them.

I often use gardening as an example that part of what we’re doing is emotional gardens, that we’re trying to create conditions to enable these plants to grow, these children to grow. The conditions that we create are vitally important. Once we’ve got those conditions right, growth will occur.

Winnicott actually described that the growth inside a bulb, I mean, the growth is there within the bulb. It’s not, you’re creating conditions for that growth to occur. And it’s a bit, and I feel that’s very crucial in creating therapeutic organisations that we have to realise that the growth potentially is there within the person and our job is to create the conditions for that.

Welcome everyone to the Secure Start podcast. I’m Colby Pearce and joining me for this episode is a highly respected former leader in residential and therapeutic foster care in the UK. I say former because he is now retired and has been for the past 10 years.

Nevertheless, I could not pass up this opportunity to talk with him and anticipate that listeners will enjoy our conversation too. Before I introduce my guest, I’d like to acknowledge the traditional custodians of the land that I’m meeting on, the Kaurna people and the continuing connection that they and other Aboriginal people feel to land, waters, culture and community. I’d also like to pay my respects to their elders past, present and emerging.

My guest this episode is John Whitwell. Now, John was formerly a UKCP registered psychotherapist and a full member of the British Psychotherapy Foundation. John was also the chair of trustees of the Gloucestershire Counselling Service and trustee of the Planned Environment Therapy Trust and the Mulberry Bush organisations.

Between 1985 and 1999, John was the principal of the Cotswold community, a pioneering therapeutic community for emotionally unintegrated boys. Thereafter, between 1999 and 2014, John was the managing director of Integrated Services Program, the first therapeutic foster care program in the UK. I’m very much interested to hear John’s views working across these different types of elder home care.

I hope you will enjoy our conversation too. So welcome, John. John Whitwell Pleased to be here and having a chance to talk with you.

And just because you are from the UK and will hopefully have people listening from other parts of the world, that little intro that I gave about the Kaurna people and the local Aboriginal people is something that is more and more characteristically being done in Australia at the beginning of meetings. It’s a sign of respect and acknowledgement for the long history of Aboriginal people’s ownership of Australia prior to white settlement. So John, I really enjoyed catching up with you a couple of weeks ago and getting a bit of a sense of what our conversation would look like.

I really want to start because our audience, of course, didn’t have the benefit of being part of that conversation. Can we just start with the Cotswold community and perhaps if you could give me a brief description of the community and your role there over time? Sure. Well, the Cotswold community was an unusual place by UK standards in the fact that it was based on a 350 acre farm.

And the reason it was there was that it was an approved school from 1942 till 1967. And approved schools were basically like junior borstols or young offenders institutions. The boys were sent to the approved school by the courts for offences that they’d committed.

And they actually had a term of, I think it was probably up to two years, and they could earn their way out earlier. Very similar to the prison system, but for good behaviour. But the approved school system in the UK was coming into disrepute and more and more research was showing that far from rehabilitating young offenders, they were actually leaving approved schools and having a higher rate of reconviction than they were before going.

And then there were various scandals which hit approved schools as well, which hit the headlines of abuse in approved schools. So the writing was on the wall for their future. And it was at that time that the organisation that was running the approved school, it was a charity called the Rain Foundation, decided when the headship became vacant to really go for a very radical change, a very brave change, really, and a pioneering change.

And they were supported by the government, the British government, in doing that, because the British government were already working on abolishing the approved school system and creating something else. So they were interested in this change taking place at the Cotswold school to see, to give them some ideas about how things could change nationally. The crucial thing in that process was appointing Richard Balbirnie as the principal, because he was very, very clear what he wanted to create.

And he needed to be sure that the Rain Foundation were going to back him 100% in that. And also the government as well. And it was needed, because I think everybody knows that if you change an institution radically, you’re going to have a tough time.

And he didn’t have the luxury of closing the place down and reopening with new staff and new children. I mean, basically, he had to bring about change on the hoof with whoever was there. And that’s a really hard thing to do.

And it was very graphically described in the book by David Wills, called Spare the Child, which was came out in the early 1970s, a Penguin paperback. So it was actually very available in just about every bookshop in the country and very readable too. I think that’s one of the crucial things I’d say about therapeutic communities and therapeutic organizations is that they need to have good leadership with a good understanding of the task.

And sadly, one of the things that I’m going off on a bit of a tangent here, but one of the things that I saw happen in the 80s and 90s in the UK, that organizations were worried about the kind of financial situation. So they started to appoint more business people in leadership roles. And that often proved to be fatal, because with all the best one in the world, those people didn’t fully appreciate the fine balance that there is in running a therapeutic organization, and how quickly it can go wrong.

So coming back to the Cotswold school, so Richard Bell Burney, overnight abolished all the things that had been keeping the thing ticking over previously, like corporal punishment just stopped. And these things don’t seem like big deals now, because we don’t have them. But at the time, it was a very big deal.

And the staff were not in favor, the staff were afraid that if they, if someone abolished all the kind of punishments in the place, which was, in their view, keeping things kind of steady, it was going to be chaos. And actually, it was chaos for a while, because the staff weren’t behind the changes. And most of the young people, the boys who were here then, took it as weakness and spent an awful lot of time running around and on roofs and, and so on.

So it required a lot of support from the organizations involved, particularly the charity and the government, not to pull the plug on this when they saw things going a bit awry and realize that this, this was something you had to go through. And I suppose I’d rather likened it to what happened really, with the collapse of the sort of Berlin Wall and the collapse of sort of communist regimes in Europe that everybody initially thought this was fantastic. And then chaos ensued.

And then people started to want to go back to the way things were before, because at least it was the devil they knew. Yeah. And that was one of the processes and one of the difficulties in the change that took place at the Cotswold School.

But Richard Balbony was was very clear in the direction he wanted to take things. And I think it probably took about three or four years before the therapeutic culture was really established. It involved bringing people in, he had to sort of sift out through the staff that were there, those that were going to be positive about the change he wanted to make.

It was also crucial for him to bring in Barbara Drucker Drysdale as the consultant child psychotherapist. And she was already well established and well known in the UK through her work in starting and running with her husband, the Mulberry Bush School, which I’m pleased to say is still going very strongly and doing great things. One of the very few places that probably almost the only one that survived from the sort of 1940s and 50s and has continued and managed to adapt and change and still keep its primary task.

Incredible. It is. It’s quite really, very remarkable.

But Barbara Drucker Drysdale and Richard Balbony had worked together before. And so they he knew that she was going to be very much on board with what he was wanting to do. And of course, her understanding through her own work as a child psychotherapist and her cooperation with Donald Winnicott meant that she was able to bring in the philosophy and the practice and the understanding of working with emotionally unintegrated children.

And these are children who are have got no very little capacity to manage their own behaviour, are very chaotic. Inside, they’re really very small children, indeed, even though they might be 11, 12, 13 years of age. And very, very difficult to look after in group care, because they are very disruptive.

Naturally, it’s their need for attention often comes in out in such negative ways, which is difficult for staff to cope with. Because it tends to bring about sort of quite quite a negative reaction, rather than an understanding reaction as to where they’re coming from. Yes.

So building that culture took quite a time. And it did mean having to use the term, it sounds a bit kind of brutal, but weed out those staff that weren’t really weren’t really aligned with that. But that was done.

And with, as I say, with the support of the managing organisations behind the Cotswold community. So the farm was quite important. I mean, in the approved school days, it was used very much to send boys out to work on the farm.

But really, that changed dramatically. For the Cotswold community as a therapeutic community, it provided a very positive environment. I mean, when you’re surrounded by the sort of chaos of children, to actually look out the window and see somebody doing an ordinary job, doing ordinary things like ploughing a field or, or bringing in some cattle, it’s kind of just kind of brings you down back to earth, literally back to earth.

And, and some of the boys also enjoyed helping out on the farm. They weren’t made to do it, they wanted to go and help feed the cattle or be involved in the lambing season or helping to stack bales after harvest and things like that. I mean, they, it was something that was an additional part of their life, which made life interesting.

And of course, most of the boys who came to the Cotswold community came from city, inner city areas. And so for them, it was a big change. And initially, they possibly found being in the quietness of the countryside quite difficult, but that didn’t tend to last long because they made sure it wasn’t very quiet for very long anyway.

So the Cotswold community was a completely kind of integrated environment. The boys lived in four separate households, quite small groups by those times, I mean, in groups of up to 10. Nowadays, 10 is regarded as quite a large group.

It was interesting then, we were actually bringing groups down from the size of 20 during the preschool times to, to under 10. And the households that they lived in were quite self-sufficient, they had their own staff teams, they cooked their own food, they did everything together. They also, I mean, had their own garden and territory, which was theirs, which they looked after and their space.

There was a school there as well. So the boys went to school within the Cotswold community, it was completely separate from the households, they, they walked to school, they had their own, they had their own school groups. The teachers who worked with them in school also came and helped out in the households for some time in the week.

And again, crucial, the crucial part of all that was really good communication between all parts of the organization. And that’s what a lot of the boys, their unintegrated personalities meant they needed a very integrated environment to hold them, contain them, to manage them. So if there was something went wrong in the school, it was vitally important that that, that information came back to the household straight away, and vice versa.

So the people working together, there wasn’t, it wasn’t, it was trying to reduce the possibility of splitting between different parts of the organization. And again, I see in the UK today, I mean, it’s very easy for a child to have a problem in school, and for the parents not to know for weeks. And vice versa, as well.

The school doesn’t know that this child is coming into their school every day, and is having to deal with huge problems at home. The Cotswold community had to avoid that. And, and it did so very well.

There was a lot of time spent in, in discussions and meetings between all the all the all the different staff. And that’s something that Richard Balbony knew was very vitally important and encouraged. One thing I haven’t, I haven’t really focused on and mentioned is the importance of the organization having a clear primary task.

Yeah. That was something that Richard Balbony brought to the, to, to the Cotswold community. And the clear primary task was helping emotionally unintegrated children.

Now, the reason that was important was because there were many other groups of people working in the community. There were also administrators, we had a maintenance team, who looked after the place and helped fix broken windows and stuff like that. We had the farming staff.

We had people who helped to come in and cook and clean and so on. All those people also had to take on board the primary task and realize. So the maintenance team, for example, I use this as an example, could feel very fed up that they just repaired a window and the following day had to come back and repair it again.

And understandably, they could feel frustrated about that. But they also had to and were helped to understand that this was the nature of the work and it was nothing personal. No one was attacking them, but they, they needed to get behind all the work that was going on.

And when there’s damage, it’s really physical damage, it’s really quite important that it’s fixed quickly, because if you just leave it, it just builds up and you get more and more. As we know, as we see in society generally. And interestingly, if I can switch to ISP, very briefly, one of the things that the lack of the primary task in some groups there was very clearly shown to me early on by the drivers at ISP.

ISP, because it had to, unlike the Cotswold community, obviously wasn’t on one side, and it had to help ferry children around to get to school or get to different sort of parts of the care that they needed, had cars and drivers who would help take children somewhere. When I went there, their reason to be was keeping the cars clean. And they would get furious if, and they banned children taking drinks or food into the cars because they just didn’t want to mess.

I had to, one of the things I had to do is kind of say to them, look, your task isn’t to keep cars clean, your task is to help these children who are finding transitions incredibly difficult to get from A to B and get to B in a reasonable emotional state. And it might be to have a contact meeting with their birth family, or something really important like that. And they might be quite worried about it and what’s going to happen.

So it might be really important that they can take some food in the car during the journey, because we know that emotionally integrated children often find that a great comforter. But that’s just another, I mean, it’s a kind of, in a way, a small example, but how important the primary task is, because it gives you something to measure things by and refer things to. So if you’re having a problem with a staff member, who isn’t really getting it, you can remind them and say clearly how, why this, why it’s important we do what we’re doing.

Yeah, it’s interesting hearing you talk about the primary task. And I’ve always thought about the primary task as being that one thing that all the rest of your endeavour is kind of supported by or rests upon. And I’m hoping we’re aligned in that, in I guess that definition.

And I think you’re right. The point that you make, and there’s so many points, there’s so many things I could pick up on from your description of the community. But I think the alignment of the staff to a common purpose, it’s still very much important to ensure that in any endeavour that that is being undertaken in this space, in the out-of-home care space, that there is alignment of the major players in doing that.

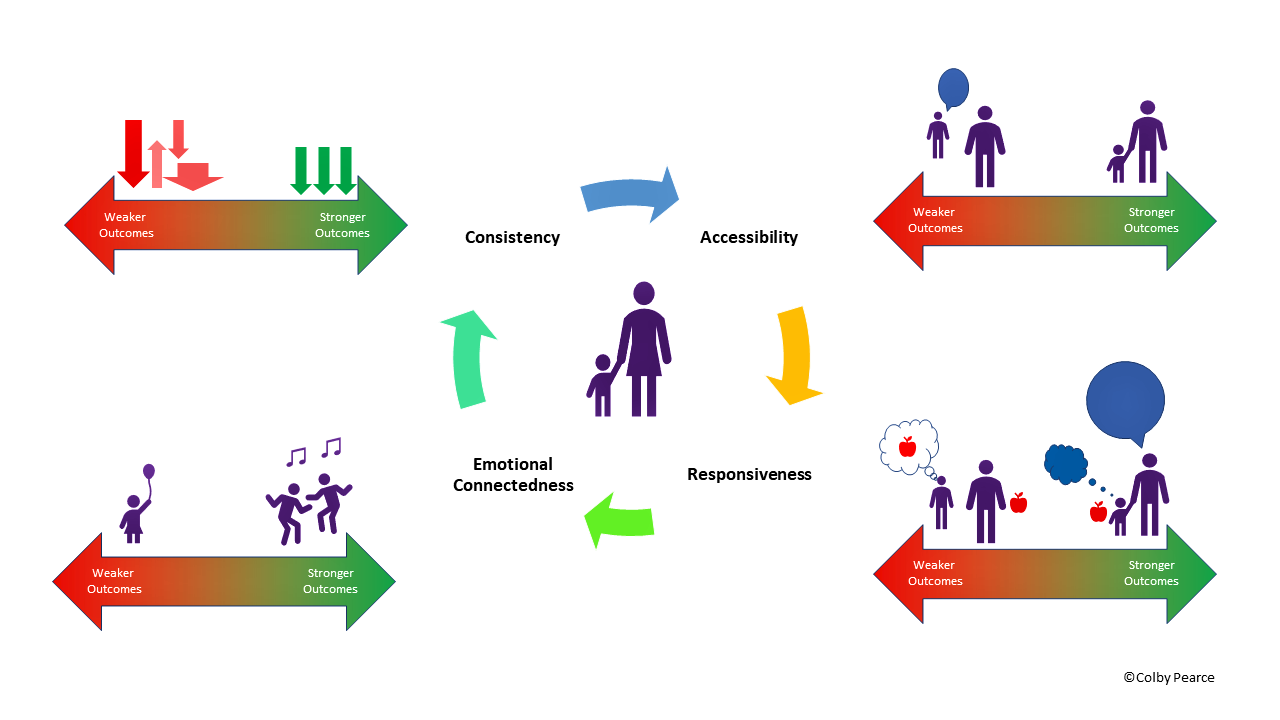

It doesn’t take much to trigger or otherwise bring about a return to chaos. I think of the primary task in the work I do, John, as being connection, that connection, our relationships, our reparative relationships with the young people. But it’s followed very closely by consistency.

Because what we know about our client group, about the young people, is that their first learning environment or even environments, their history of inadequate care, of difficult care, of early adversity, was characterised by inconsistency, inconsistent parental responsiveness. Because generally speaking in this space, parents, it’s not the case that the children were never cared for, but it was the care provided by parents was inconsistent, often due to the other factors at play in their lives, the things that were getting in the way of them being the best version of themselves as a parent. So I think alignment is crucial.

Any misalignment, as you described with ISP, with the drivers, that can just be that one thing, that the young people might have the thought, you know, I knew it. I’ve had all these people being nice to me or responding to me with understanding, but this one experience can then become generalised to, I knew it, you’re all the same, my beliefs, my understanding of how relationships work, have been confirmed just by this one experience with a driver. Yeah, yeah.

And I agree very much so with what you’re saying. When you said about the primary task and where it originated from, I mean, I don’t know that these people actually did it, but one of the other consultancies that was vitally important for the Cotswold community was from the Tavistock Institute. And that started with Ken Rice, A.K. Rice, who was very well known.

And he wrote the first working note of the Cotswold community with a kind of organisational structure. Because in order for the Cotswold community to work as a therapeutic community, it had to change the whole way the organisation was structured. Because as an approved school, it had been very top down, with the headmaster having or being all powerful over everything.

Richard Bell Burney turned that on his head because he really wanted the people who are doing the direct work with the children to have the confidence and the ability to be able to make decisions, to be able to be good role models of being kind of caring, responsible adults in the children’s lives. And the approved school system was the exact opposite of that, because the people who were at the coalface were seen as the kind of least important people in the organisation, whereas they became the most important people in the organisation, really, for the therapeutic approach to work. And Ken Rice started that.

Unfortunately, he died two years after doing that. So his consultancy ceased. And then that was taken over by Isabel Menzies-Light, again, who was a very well known organisational consultant.

She’d worked, she’d done a very well known study on nursing in hospital, and how anxiety was managed by nurses in that organisation. It’s still a classic work. And she worked with the Cotswold community for about, I suppose it must have been about seven or eight years.

And then that was, from the Tavistock, was taken over by Dr. Eric Miller. That line of consultancy was vital, because it wouldn’t have worked, I don’t think, had it been just Barbara Drysdale on her own, yeah, working away at the day-to-day interaction with children, that was vitally important, crucial. But if the management structure had not been around to support that work, it would have just come undone very quickly.

So the two threads of consultancy, the two aspects were so crucially important to the success of the Cotswold community. I can’t stress that enough. And I personally learned a huge amount from both consultancies, really.

And Isabel Menzies, let me, for example, I’ll give you an example of some of the things that she focused on. She was a great believer in the value of scarcity, which may seem a bit of a contradiction in terms of what we’re talking about. But she believed that, as in families who have to work together when they haven’t got infinite resources or infinite money.

So as a therapeutic community, we’re in the same boat. And we sometimes have to face the fact we couldn’t do everything we wanted to. We couldn’t have as many staff as we wanted to.

We couldn’t have huge amounts of money for having banquets every night or, I mean, and how we worked at that scarcity was really, really important for the children that they were a part of figuring things out. Like, OK, we would like to do this, but actually we can’t. So what can we do with the resources that we’ve got? And it was a really important kind of learning experience for us all, not just the children.

I mean, as adults, we were kind of learning all the time through that. So I really valued Isabel Menzies’ life’s work on the importance of scarcity and how you manage it. I mean, again, there’s so much I can pick up on.

I think it’d be interesting for our listeners to hear how much contact staff were having with these external consultants. And so, you know, at what frequency and regularity was that contact happening? And I think also, I want to put this into the same question, although they might be best treated separately, I’ll leave it to you. But what was the prime, you’ve taught, referenced the therapeutic approach.

What was the primary therapeutic approach that that they were supporting? OK, well, take Barbara Drysdale first, because she was the probably the main consultant for the community. Bear in mind, we had four households. She came, she didn’t do a long day, probably she came for about five or six hours, three days a week, and saw each of the staff teams once a week.

But she also had time to see individuals, some individuals, I mean, not everybody, you basically had to, to queue up to see her, so to speak, individually, but you might get a chance every two or three weeks to see her for an individual consultation. And the consultations were quite brief. I mean, there were no longer than probably half an hour for individuals and for a group no longer than an hour, which, you know, is quite brief.

But she had also, that suited her style, because she was probably quite a directive consultant, which may sound a bit unusual for a child psychotherapist who might be characterized as somebody who sits in silence most of the time. But she wasn’t like that. And that was probably quite important in the early days, if you were going back to when she started with Richard Balbony.

She really had to be quite definite about what was needed to be done. And that meant probably saying and talking more than probably most consultants would normally do. But this was about establishing initially the culture.

Yeah. So three days a week, for five hours or so she was there in by today’s standards, that’s that’s a lot of contact and involvement with with the organization. And she also met with the education school staff as well.

So many groups had a chance to meet with her. And it was all part of everybody getting on board with the primary task. There were other consultants who came in less frequently.

I mentioned the Tavistock Institute, they would probably come and spend a day with us once a month. We also had an educational psychologist who worked with the education staff team. And that was probably also once a month.

And we also had somebody was difficult role, a person called Dr. Faye Spicer, who was a psychiatrist who came in and it was an unusual kind of role for her to take because it was a kind of on that sort of medical psychiatric boundary. Bearing in mind that there would be times when we as an organization would be quite worried about the risk we were taking with a particular child who was perhaps exhibiting some very extreme behaviors. And we needed we needed to work on this and discuss this with a psychiatrist who could help us look at what how to manage that risk.

What was the what was the reasonable risk to take? And that again was probably for once a month, really, sometimes a bit less. It’s a well supported team with with different functions, different functions from care staff to teachers at the school, everyone in alignment. I’ve often said, and this is part of the reason why I’ve developed programs for professionals, for carers and for schools is what it’s the actual reason why I’ve done all that is because I think the best outcomes are achieved by getting alignment in all the major domains of a child’s life or at least as many major domains of the child’s life as you can get that alignment.

You mentioned that it took about four years though to and that would be a struggle that a lot of contemporary residential care providers would identify with, which is getting all the staff in a program, I guess, singing from the same hymn sheet. So it’s rough. I think there are probably factors there with it having previously been, I guess, what in my parlance would be a reformatory and staff that had a different role and then having to take on a more therapeutic role that may well have elongated the process.

But I think that that challenge of getting everyone, as I said, singing from the same hymn sheet is still a contemporary challenge. I wonder, do you think that the frequency of involvement with Barbara and with other consultants, what role you think that had in terms of facilitating alignment, a live focus on the primary task? Yeah, I think it was exceedingly important. I mean, to give you another example, the frustration sometimes that a group living household staff team could feel when they were dealing with some sort of very, very challenging behaviour with the best will in the world could lead that team to believe that they just need to get rid of this child to make everything all right, because this one child is absolutely taking everything apart.

So the staff team would go to Mrs Drysdale, Barbara Drysdale’s consultancy in a frame of mind that wasn’t very therapeutic, in all honesty, was probably thinking, are we, to survive, we’ve got to get rid of this child. Can you support us do this? I mean, wouldn’t come out as clearly and sharply as that question, but everything that would be presenting and what they got back from Mrs Drysdale invariably was, no, we’re not going down that road. What we are going to look at is actually how things develop like this, because one of her key principles was that the acting out of children was down to a breakdown in communication.

And that invariably meant that you, it put pressure on the adults to help the child to communicate, not to complain about their acting out, but to come back to the origins of it. And usually there were things which we as adults had missed. And it could be something fairly obvious, like some contact with a birth parent that had really upset the child and bottled it up and then exploded, exploded over something quite trivial.

It might have been just an ordinary frustration, which instead of just being, you know, the exhibiting frustration had become a huge explosion. And then when you actually got to talk with the child about that, they would probably relate it back to something that had happened a few days before, which, which people had missed at the time and hadn’t realised. It’s that sort of thing, unpicking, unpicking things.

And of course, it’s tremendously good for learning as well. I mean, it does bring people together. And I was going to say the role of consultants go back to your question, I think is very important in helping people to understand that and, and keep on task.

So it’s interesting to hear that, because just as an example, what I’m referencing is Barbara Docker Drysdale’s reference to communication. And because I think 30, what are we now? 40, 30, 40, 50 years later, people are again, or maybe still talking about behaviour as communication in, in, and whether that’s exactly the same as what Barbara was talking about, or a little bit different, but there is very much in the community, therapeutic community in out of home care. These days, there’s very much a focus on understanding what the child is telling us through their behaviour, telling us about their experience through the behaviour.

So less of a focus on on the behaviour itself and more on more of a therapeutic response to the reasons for the behaviour. Yeah. The other aspect of communication I haven’t mentioned, which Barbara Docker Drysdale, in her writing, demonstrated that she was very, very gifted at communicating with children symbolically through through their play.

And, and that’s, that’s something that she helped to develop in the community so that she would encourage different play materials to be available. And so that when, when, when the focal carer to a particular child had individual time with him, and they would they would often be playing, it might be in sand with various toys, and helping to sort of see the world that the child was creating and, and kind of respond in a sort of sympathetic way, you know, in a in a way which isn’t taking over from the child, very much not that, but can get alongside. And it’s quite a quite a skill that nothing.

Well, I’d say it’s a gift almost, because I’d be the first to hold up my hands that I’m not great at symbolic communication. Whereas someone like Barbara Docker Drysdale was just brilliant at it. And when I saw her with children, I mean, you know, it was like, she was kind of entering at another level in terms of communication.

So that was an example, I suppose, of being able to not wait for acting out for communication, but to sort of get in and understand the inner world of the child through playing. Yeah, absolutely. John, I feel like we could talk for hours about the Cotswold community.

I’m aware that I also want to talk to you a little bit about your other major role of your career. Before we move on to a brief discussion about ISP, overall, how would you describe your time at the Cotswold community? Initially, it was very, very hard. And I nearly didn’t survive it, I have to say.

Because it was, I went to the Cotswold community thinking I was quite experienced, because I’ve had three years working in a probation hospital, only to be completely flattened by the fact that I knew next to nothing about a more psychodynamic approach. I was having to start again. And the other difficulty for me was being assigned to a household that hadn’t achieved a therapeutic culture.

And we were struggling, we were struggling in all honesty. So my first year there was a tough one. It did me some good, I have to say, looking back, because it helped me appreciate how easy it was to slip back from a therapeutic culture into something that wasn’t, you know, groups are fantastic, when they’re very positive, and they bring everybody forward and take everybody along.

But there’s also a very negative side to groups as well. And if a group is in a downward spiral, everybody gets infected by that. So that was a really crucial lesson for me to learn very early on.

And I spent a lot of time making sure we never went down that road again. I mean, I suppose everything I did subsequent to the Cotswold community was based on what I learned there really. So having the privilege to work with the consultants we had, I can’t think of another environment in the UK that I would have had that experience.

So yeah, it was very hard, but very, very positive, and enabled and gave me a real sense of direction in terms of what I wanted to do. And which certainly helped me when I moved across to ISP. And perhaps I should just say briefly, the reason I decided to move, partly from the fact I’d reached the age of 50, I thought, if I’m going to do anything else in my life, I have to go now.

Otherwise, I’m really past my sell-by date. But also, I began to feel there were lots of pressures on coming, which I thought were going to make residential therapeutic work harder in the UK. I mean, staff were increasingly working shift systems.

There was a lot of anxiety about risk taking. Understandable, because there’d been some pretty awful things happened in residential institutions in the UK over the years. But it just felt that the reaction to those awful things were just going to make it more and more difficult to, in my view, to do the work.

And I’d go as far as to say that had the Cotswold community been thought about in the 1990s, I don’t think it would have happened in the UK, in all honesty. Certainly, I think Richard Dalbernie and Mrs Drysdale, because they were so kind of determined about what they were doing, I think might have struggled to get the backing of the organisations that they were able to get the backing of at the time when they started. I may be wrong about that.

That’s just my personal view. But anyway, it led me to think about moving. And I saw an opportunity with the integrated services programme, which had been started by foster carers in 1987.

So I went there in 99. So it had been going for a good few years already. And they were looking for someone to take on the overall management of the organisation who had experience because they tried the twice in my working life, I’d taken over from the charismatic founder directors.

My role in life was not to be one of those people, but to be the next generation. And so it was interesting, I didn’t, I didn’t actually at the time consciously do this. When I look back, I think, well, that can’t, that can’t have been accidental that I ended up in two organisations as the next leader from the founder director.

And the ISP had had two goes at recruiting somebody to take on from the from the founder director, and both had failed. So they were looking for someone who had more of a track record in therapeutic care. And that’s why I got the job.

It was a difficult job to take on because it’s, it was very different organisation to a therapeutic community. Naturally, the carers, it’s more fragmented. I mean, the carers, the care is going on in everybody’s individual homes.

And so whereas we had the benefits of the Copswell community of everybody being together on one site. And so I described earlier, you could, you could aim for good communication between all parts of the organisation almost instantly. That wasn’t the case with ISP.

So I had to work at that was one of the things we really had to work hard improving communication. And one of the syndromes of deprivation that Barbara Docker Drysdale identified was the archipelago child. And these are children who got pockets of functioning amongst a sea of chaos.

And the therapeutic task with these children is to help to grow the pockets of functioning. So they start to gradually join up. And the sea of chaos diminishes.

That all sounds very sort of graphic and, and a bit, a bit poetic, but it is. But it is basically what we’re trying to do. And it can take a few years with a child to achieve that anyway.

But I saw ISP was like that ISP was like an archipelago child. There were pockets of good practice going on. But there was also a lot of stuff that needed sorting out.

And I found my task was really how can I help build on the good things that are there. And it took a few years to achieve. One of the reasons why I was so keen to speak to you was what lessons you or what understandings did you garner or attain while you’re at the Cotswold community that that were of a benefit to a therapeutic foster care service? I think there were a whole variety of things, really.

One of the first things I think one of the first things that ISP had a difficulty with me when I first arrived, was that I wasn’t prepared to give instant answers to things. They had a culture of, of expecting, whenever there was a problem, that the founder, director would give them an answer straight away, sort it out. Didn’t have to be the right answer.

They would just get an answer. When I came in, people would would be banging on my door or phoning me up and saying, what do we do? So actually, I don’t know. Let’s think about it.

And that was a complete culture shock for them. I mean, I think initially, they saw me as a complete idiot who didn’t know anything. But fortunately, again, I had the support of the board of directors.

And the chairman of the board said, Do you know, he said, I, I just, I just gave three cheers when you when I heard the word, the words, I don’t know. It’s the first time that it sort of heard it. That was kind of one thing, that that capacity to stop and think and reflect, not, not react instantaneously.

So vital practice, the opportunity, stopping and thinking about what you’re doing and why you’re doing it. Yeah. And this was trying to get that through to foster parent carers as well.

Because I mean, there was much in the practice of foster carers, which was which was very good. And you would certainly probably put it in the bracket being therapeutic. They wouldn’t necessarily know that they were doing that.

And that was one of the things I wanted to sort of build up in the organization was the whole training program for foster carers, whereby they could appreciate what they were doing and also understand some of the behaviors they were dealing with, because they also suffered the same things that we did at the Cotswold community where a child would instead of lapping up all the great care would throw it back in the carer’s face. And, and that lack of gratitude for being looked after is something that I think a therapist has to learn that you’re going to have to weather those sort of storms without expecting to be thanked for it. So linked to that was also the importance of consultancy.

Now, ISP when I arrived there had quite a number of therapists working working there already. But their role was entirely to see individual children for individual therapy when it was needed. And the change I started to bring about was using those therapists in a different way as well, where they could, they could be involved with the staff team discussions, they could also, because there are many children who might, people might say, well, they really need to have individual therapy, but the child is nowhere near wanting it or ready to use it.

But the carers would benefit greatly from having a regular time with a therapist to help understand what was going on, as indeed, the residential workers at the Cotswold community did. And so that was that was a really important change I made. It did mean we had to expand the therapy time in the organisation to allow for that, because there were still children having individual therapy as well.

But a much more that was the development of the network around the child of all the different people working. I mean, obviously, crucial to that was the foster carers. But there’d be this, the social workers in the organisation, the therapist, we also had and developed what we called advisory carers.

These were people who’d been experienced foster carers, who were able to take on a role supporting newer foster carers, based on the on hard-won experience. Because one of the things that foster carers really got very fed up about was being talked down to by social workers, as they saw it, who’d never once in their life had a child, never once looked after a child, and felt that they were being kind of seen as second class citizens professionally. Whereas we were making them, these were absolutely vital, crucial to the child developing.

And the network around the child was also a network around the foster carers to support them in that crucial role. And these are the advisory foster carers knew that, I mean, because they’d done it. And that was that was a very important part of the culture.

Yeah, so it impresses upon me in both as a culture of continuous growth through education and support from significant others. Yes. Yeah, we, the training programme in both the Cotswold community and ISP was really vital.

I mean, because we would take, I mean, at the Cotswold community, we were taking in quite young staff, who’d not necessarily been very experienced. And we had to select them very carefully to have the potential to learn. And they had to come into an environment which was going to support them.

Because there weren’t at that time, I mean, I know things have changed since, but at that time, there weren’t qualifications, which meant someone could walk straight in and do the work. We had to provide that training environment there. And in a way, the same for the foster carers, we had to provide, enable them to develop the tools that they’re going to need and the understanding that we’re going to need.

So we had a, we had a three year training programme for foster carers. And we had a whole range of, of trainings that we would expect them to go through and to embrace. And that was, that was something that really took a while to develop.

But gradually, as people saw the benefits of that, and they saw the way children were, were growing and developing themselves, I mean, they got a lot of positive feedback. It reminds me, it reminds me of something that you talked about at our, you know, previous, just initial meet, when you talked about our mutual connection, Patrick Tomlinson, who introduced us, and you telling me about how he kind of organised training for staff at the Cotswolds community. And I had, if we had more time, if we had another time, it would be really good to have a bit of a chat about that from your end.

Of course, I can also speak to Patrick about it. Hope to have him on the podcast as well. So much to talk about.

John, I feel like I could sit here for hours, but unfortunately, I don’t have those hours and we’ll need to kind of make some final comments. But before we do, you did refer earlier to the advice that you would give to leaders in residential and foster care endeavours these days. But I wonder if you might just quickly say again, what advice from your long career working in both aspects of our home care that you would, you think is probably a bit like the primary task, the most important thing, piece of advice that you could give them? Sorry, that’s a bit of a question.

That’s quite a difficult one. Yeah, I think that really comes to mind. And I can remember, actually, you mentioned Patrick, I remember talking this over with Patrick quite recently.

And that is, we know that outcomes for children are really important. So what I’m going to say is not in any way denying that. But my worry in the last few years in the UK has been the focus on outcomes to such an extent that I think there’s been a misunderstanding.

Because all that I learned at the Cotswold community and subsequently at ISP is about, if you get everything in place, if you successfully create this therapeutic culture, the outcomes will come. The outcomes will come. And I think the focus on outcomes, my worry is, it’s a silly example, but it’s a bit like, I often use gardening as an example, that part of what we’re doing is emotional gardeners, that we’re trying to create conditions to enable these plants to grow, these children to grow.

The conditions that we create are vitally important. Once we’ve got those conditions right, growth will occur. And it’s a bit like a gardener picking up a packet of seeds with pretty flowers on, showing it to the seeds.

This is what you need to do. This is what you need to be like. And expect this to, whereas, I mean, you know, it isn’t going to be like that.

Winnicott actually described that, you know, that the growth inside a bulb, I mean, the growth is there within the bulb. It’s not, you’re creating conditions for that growth to occur. And it’s a bit, and I feel that’s very crucial in creating therapeutic organisations that we have to realise that the growth potential is there within the person.

And our job is to create the conditions for that. And it’s not easy. And there’ll be many things to test you along the way.

And you need to also be have the support of other organisations around you to do that. That’s that that is kind of, I think, one of the most important things I’ve learned, I would say. I love it.

Yeah. Bruno Bettelheim, if I can just very quickly say just something’s come to mind. Bruno Bettelheim was asked by somebody, what is a cure? And he said, Well, it’s, it’s doing the best you can every day.

And then it might add up to something. And you might then at the end of the process say, that’s a cure. But at the time, you don’t know, you’re just doing the best you can every day, for as long as it takes.

Yeah. And I thought that’s, that’s, I like that. I thought it was pretty, pretty good.

It’s a great, it’s a great metaphor and reminder. Just before you leave us, John, if you could give your younger self just starting out your professional journey, some advice, share some knowledge with them, with them that you wish you could have had advice you could have had or knowledge you wish you could have been had as well. What do you think it would be? Well, again, that’s difficult.

Because if I sometimes say to myself, if I knew everything I knew now, why don’t I go back and do the same thing again? Because, because sometimes ignorance is bliss. And when I went out, when I kind of stumbled into doing therapeutic work, I didn’t fully, in all honesty, I didn’t fully appreciate what I was getting into. And, and some of the things that I some of the knocks I had to take and, and the tough times I had to put through my own family, I, you know, I think, would I do that again? I hope and think I would.

But you know, sometimes, you do take a leap of faith. And, and for me, when I was working at the probation hostel, I came across this book by David Wells, I’d mentioned before, called Spare the Child, which was about the change coming at the Cotswold, that was taking place at the Cotswold community. And he just had a wow moment with thinking, this is all the things that I’m aware of in our hostel that we’re not doing.

We’re just, we’re not getting below the surface. And I really wanted to do that. Little did I know that getting below the surface was, was going to be really tough and would really impact on me.

And there were times when I really felt like giving up. But, but it really was, really was worth it, I guess, when I look back, and I’m pleased I did it. Sorry, it’s not really the right answer to your question.

But it’s what comes to mind. Yeah, it’s an answer. So look, John, that was it was a very enjoyable conversation and very enjoyable to hear more from you.

I will include in when I distribute or advertise this podcast, the link to your website, which has lots of valuable information for people working in the sector to access. And look, on behalf of our listeners, and also myself, thank you very much for agreeing to do this podcast for being on and hopefully, you might agree to doing it again sometime in the future. Yeah, no, I’m very, very pleased to and thank you for inviting me.

It’s been a pleasure. And I hope I’ve said something that’s been quite useful for some people.