The content of this post is drawn from my self-paced learning module on the topic of Early Trauma: The Infant’s Experience. It was developed for carers of children recovering from early relational trauma that necessitated placement away from home. The complete module can be accessed here. I have included a sample of the content of the module, below. I anticipate that it would take less than one hour to work through the full module. You can purchase a PDF version of this and other self-paced learning modules here.

The trauma I am going to focus most on today is that which arises in circumstances where the child’s parents are struggling with their own challenges, such as:

- Mental health challenges;

- Substance misuse;

- Domestic and family violence;

- Poor parenting knowledge;

the infant’s experience of these; and their impact.

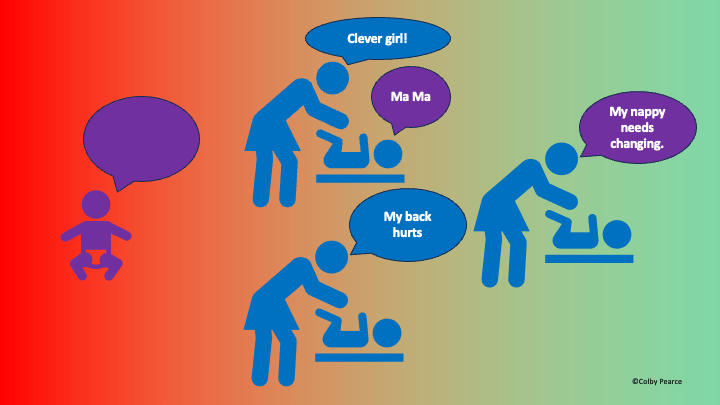

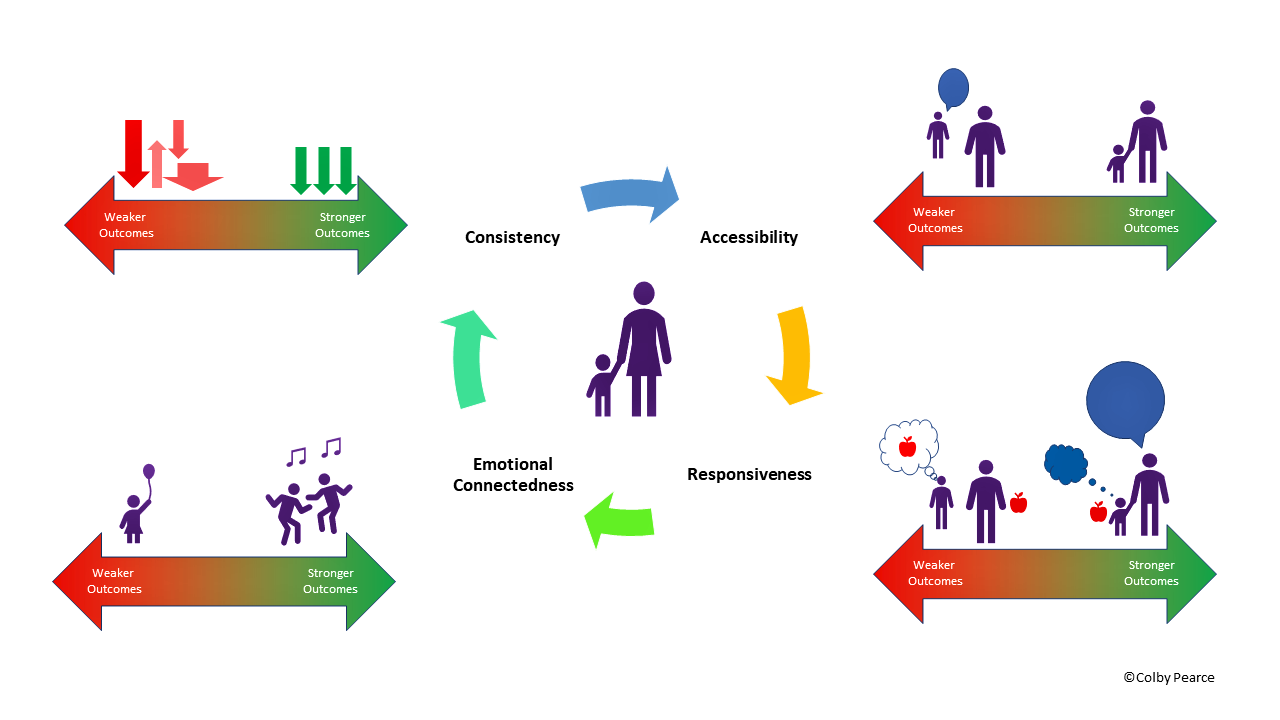

In talking about the infant’s experience I will refer to the infant’s experience of the caregiving environment and their primary caregivers. A concept I find useful when referring to these qualities is their AURA.

In converting the term AURA to an acronym, its component parts represent four key aspects of the infant’s experience of early trauma, and a clue as to where to focus remedial efforts.

A: Accessibility

In a conventional, nurturing early caregiving environment, we spend time with the infant and attend to them whether they are crying or quiet. During temporary separations we check-in regularly with the infant. We don’t leave them alone for too long. We are probably just as likely to check in on them when they are quiet as we are when they are crying. In these circumstances, the infant experiences their caregivers to be present and accessible. In time, this develops into an understanding of reliable access to their caregivers, and a caregiving response, that supports exploration, with all the developmental benefits that accrue from this, and tolerance of separations.

A particular aspect of development that is important here is the development of object constancy and object permanency. Object constancy reflects a developmental competency whereby the infant recognises recurrent aspects in their environment, including the qualities and attributes of the recurrent object. With respect to their caregivers, infant’s first learn to recognise their own primary caregivers based on them being recurrent aspects of their experience, and them presenting with qualities and attributes that are consistent and can be relied upon. That is, with respect to recognition and reliance on caregivers, they need to be accessible and consistent in the way they look and feel to the infant.

Later, in conventional nurturing care environments infants develop object permanency. Object permanency refers to the infant’s ability to form a mental representation of the object in those times when the object is absent from their direct sensory experience. That is, the infant understands that the object exists independently of their direct sensory experience of the object. What extends from object permanency is the infant’s capacity to trust in the continuous existence of their caregivers independent of direct sensory experience of them. What is likely to support this understanding is regular and recurrent separations and reunions.

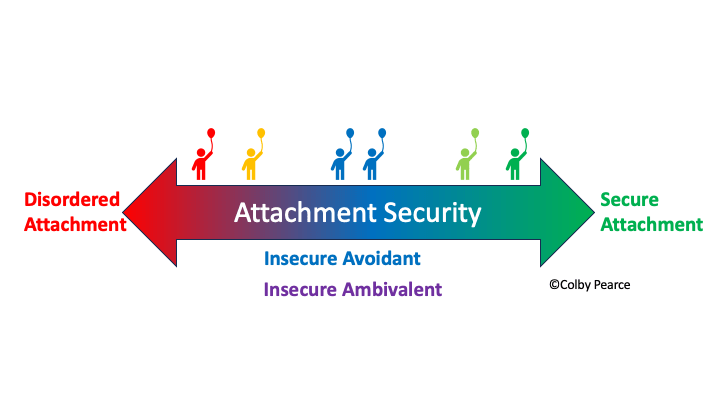

When caregiving is hampered by mental health challenges, substance misuse, relational difficulties, and/or poor parenting knowledge, the infant’s experience of the accessibility of their caregivers is impacted, with adverse consequences in terms of their understanding of who their caregivers are and what can be expected of them, especially in the context of temporary separations. These infants later present with diffuse or impaired attachment relationships and a style of relating that sees them obsessed with proximity of their primary caregivers and inordinately distressed during temporary separations. This will also be seen where the infant has had a mixed experience of parental accessibility, wherein the lack of consistency between caregivers supports uncertainty.

Interventions that begin to address this aspect of the child’s behaviour need to enrich the child’s experience of caregiver accessibility. In undertaking this task, it is important to remember how infants learn about the accessibility of their primary caregivers in a conventional nurturing care environment. They need their contemporary caregivers to attend to them whether they are crying or quiet. That is, they need to attend to the child proactively. They also need to do so at a consistent rate, such that the child can anticipate caregiver accessibility. Interventions with caregivers need to address barriers to this aspect of parenting.